In the recently-released “Defense of Japan” white paper, Japan’s Ministry of Defense had a lot to say about China as a security threat. In one of the more specific criticisms, the paper takes China to task for its “unilateral development” work in the East China Sea, where Japan and China have not yet delimited their exclusive economic zones (EEZs), thanks in part to an on-going territorial dispute over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands.

The white paper argues that China “has been continuing activities seen as high-handed to alter the status quo by force and has attempted to materialize its unilateral claim without making compromises.” In recent months, similar accusations have mostly been leveled at China with regards to its activities in the South China Sea, especially its land reclamation and island-building activities. Japan, however, remains concerned about China’s activities in the East China Sea, which are more directly relevant to Japan’s national security interests. While most of the world has turned its attention away from the East China Sea since China-Japan relations entered a period of thaw last fall, Japan’s white paper reminds the world of its concerns.

The paper specifically mentions China’s construction of offshore gas platforms in the East China Sea, a project started in June 2013. Japan believes the construction work is in violation of a 2008 agreement that would have Japan and China jointly develop natural resources in the East China Sea. “Our country has repeatedly lodged protests with China’s unilateral development and urged it to stop the construction work,” the white paper said. The report also raised Japan’s concern about regular Chinese patrols of the disputed region, both by aircraft and naval vessels.

China has denounced the white paper, with several Xinhua news reports questioning the “China threat” narrative within the report. Meanwhile, China’s Foreign Ministry gave a more detailed response to the particulars of the section on the East China Sea. “China’s oil and gas exploration in undisputed waters of the East China Sea under China’s jurisdiction is justified, reasonable and legitimate,” spokesperson Lu Kang said in a statement. On the question of patrols in the East China Sea, Lu said that “Diaoyu Dao has been China’s inherent territory since antiquity. China’s patrolling and law enforcement activities in Chinese territorial waters off the Diaoyu Dao is China’s inherent right to lawfully exercise sovereignty.”

Japan’s white paper did not specify the location of the offshore platforms in question. Analysts noted that known Chinese construction was on China’s side of the geographical equidistance line between China and Japan, which serves as a rough guideline in the absence of actual delimited EEZs. Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs admitted as much in a follow-up statement on “the current state of China’s unilateral development of natural resources in the East China Sea.”

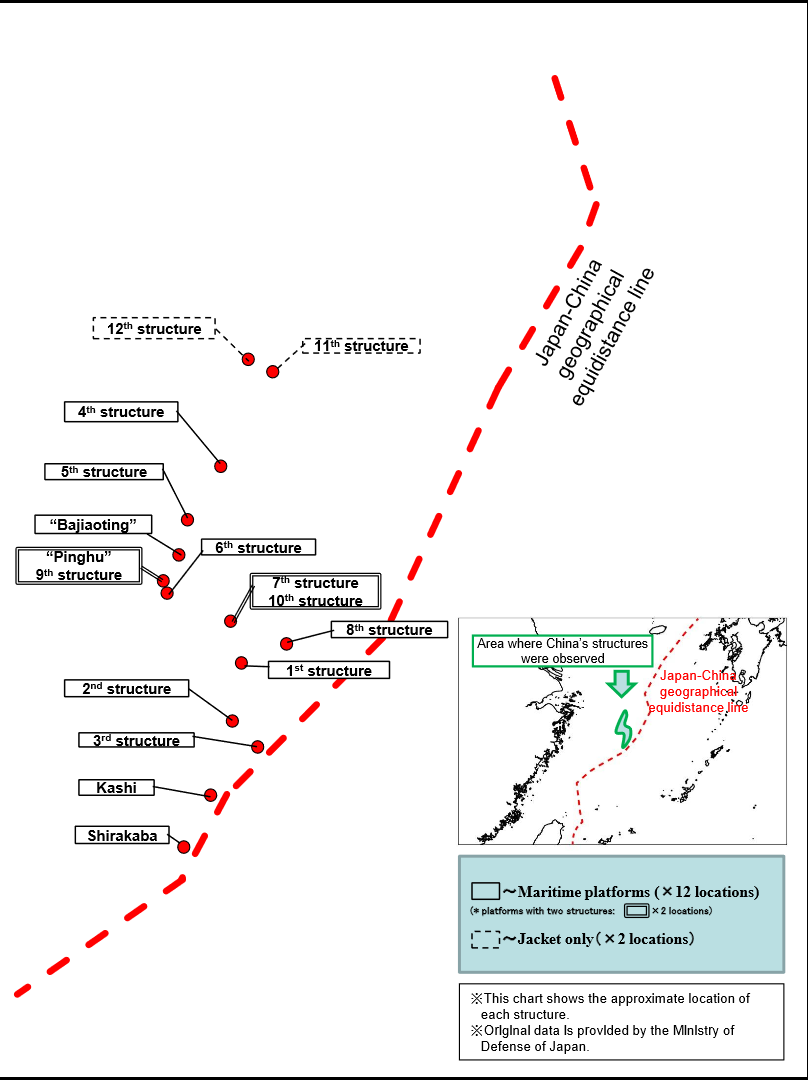

That statement said that Japan “has confirmed that there are 16 structures in total on the Chinese side of the geographical equidistance line between Japan and China.” It then argued that the structures are problematic, despite being closer to China than to Japan: “[U]nder the circumstances pending maritime boundary delimitation, it is extremely regrettable that China is advancing unilateral development, even on the China side of the geographical equidistance line.” The statement added that “the Government of Japan once again strongly requests China to cease its unilateral development.”

This time, to provide evidence, the MOFA statement provided photographs and a map of the Chinese structures in the East China Sea. The location of the features on the map is approximate, but they are well north of the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands – southeast of China’s Shanghai, and roughly west of the coastal city of Wenzhou. Most of the 14 structures on the map are set back from the equidistance line, with three (called Shirakaba, Kashi, and the “3rd structure” by the MOFA) just on the Chinese side.

This time, to provide evidence, the MOFA statement provided photographs and a map of the Chinese structures in the East China Sea. The location of the features on the map is approximate, but they are well north of the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands – southeast of China’s Shanghai, and roughly west of the coastal city of Wenzhou. Most of the 14 structures on the map are set back from the equidistance line, with three (called Shirakaba, Kashi, and the “3rd structure” by the MOFA) just on the Chinese side.

The images show maritime platforms, with notations as to when Japan’s Ministry of Defense observed construction activities. According to those notes, construction began in the summer of 2013 and was at a high in summer 2014. During those two years, China-Japan ties were at their tensest in years, thanks to Japan’s nationalization of the Senkakus in fall 2012 and Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s visit to the controversial Yasukuni Shrine in December 2013. There were only three structures that saw construction work after an ice-breaking meeting between Abe and Chinese President Xi Jinping in November 2014.

The structures appear to be mostly gas platforms, but Japan remains concerned about potential military applications. Japanese Defense Minister Gen Nakatani told the Diet on July 10 that China “could deploy a radar system on the platform and use it as an operating base for helicopters or drones conducting air patrols.” Japan also worries that, though the structures are located on China’s side of the equidistance line, they may allow China to access resources on Japan’s side of the line (again, remember that there’s no agreed delimitation between the Chinese and Japanese EEZs in the East China Sea). Interestingly, Japan’s Cabinet refused to approve the first version of the white paper because it did not include strong enough references to Chinese activities in the East China Sea.

In a press conference accompanying the release of the photographs, Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga said the structures in the East China Sea would not affect bilateral relations—but from China’s response, it seems the decision to publicly air Japan’s concern might well put a damper on the fragile relationship.

In a new statement, Lu Kang said that “China’s oil and gas exploration in the East China Sea is in undisputable waters under China’s jurisdiction, and falls within China’s sovereign rights and jurisdiction.” He added that publicizing the issue “provokes confrontation between the two countries, and is not constructive at all to the management of the East China Sea situation and the improvement of bilateral relations.”

As for why Japan decided to release the additional information, Suga said Tokyo reached the decision after China ignored repeated calls from Japan to halt it development activities. A government source, however, had a different take in comments to the Yomiuri Shimbun: “[I]t was better to publicize the data to the international community as evidence that shows China’s high-handed maritime advances following land reclamation in the South China Sea.” In other words, Japan may be hoping to follow to redirect international criticisms of China’s actions in the South China Sea by following the Philippines’ example and making photographs and other evidence publicly available.