Azerbaijan may be situated in the Caucasus, but there’s an argument to be made for lumping the country in with the Central Asian states. Indeed, sometimes it is. It’s easy to see why.

Look at the demographics, for instance. Unlike its Caucasian neighbors, Azerbaijan maintains a majority Turkic Muslim populace, numbering close to 10 million. In terms of governance, the country also stands far closer to Central Asian kleptocracies than the semi-authoritarian bureaucracy in Armenia or the rumbling democracy in Georgia. The country boasts a nominally secular government – a fact its lobbyists remain eager to play up for Western audiences. The Aliyev clan has ruled Azerbaijan for decades, solidifying its ruling claque’s reach with each passing election. (Unlike its Central Asian counterparts, however, Azerbaijan remains the lone country who has accidentally released “election results” before the election even took place.) Much like his counterparts in Astana and Tashkent, President Ilham Aliyev brooks no dissent, either from the political or media spheres. Indeed, in terms of cracking down on civil society, Aliyev has managed to outpace some of his Central Asian counterparts. Azerbaijan maintains double the political prisoners of Belarus and Russia combined.

Much like Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan has pursued a form of multi-vectorism within its foreign policy outlook. While not nearly as remittance-dependent as Kyrgyzstan or Tajikistan, Azerbaijan nonetheless maintains warming relations with Russia, both due to general autocratic consolidation as well as Russia’s swelling arms trade with Baku’s regime. Azerbaijan doesn’t maintain quite the level of relations that Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan know with China, though with the ever-expanding breadth of China’s Silk Road Economic Belt initiative, Baku’s relations with Beijing will only continue to swell. And while Azerbaijan sees far cooler relations with Iran than Central Asia – Iran enjoys a substantial, restive ethnic Azeri population – Baku has buffed its relations with Brussels and Washington for years. And while much of these relations come on the back of conspicuous bribery and underhanded PR campaigns, the relationship also comes on the back of a very real mutual interest: energy.

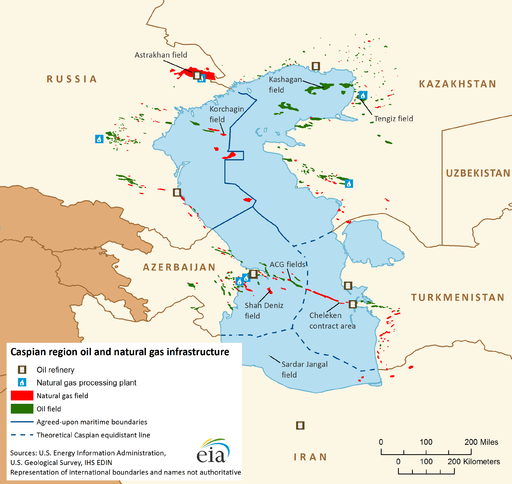

Image Credit: U.S. Energy Information Administration

Beyond demographic makeup or nationwide governance, it is within the realm of energy that the parallels between Azerbaijan and Central Asia remain strongest. Much like Astana and Ashgabat, Baku’s lifeblood stems from its hydrocarbon reserves, with over 90 percent of its exports coming in the form of petroleum. Unlike the Central Asian states, however, whose oil and gas extraction only picked up during the post-Soviet period, Baku has stood synonymous with oil export for over a century, since the Nobels and the Rothschilds first skimmed carbon from the Caspian. Likewise, and also unlike its Central Asian counterparts, Azerbaijan has managed to wend its hydrocarbon exports to Western markets in mass quantities. With the advent of the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline nearly a decade ago, Azerbaijan managed to forego Soviet-legacy pipelines through Russia to send Caspian hydrocarbons to Western markets. Moreover, that extraction and export may yet expand in the near future. With the advent of the Trans-Anatolian Pipeline, set for completion in 2019, Azerbaijan will be able to transit more of its hydrocarbon to waiting Western customers.

Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan have proven eager to push a trans-Caspian pipeline – but Moscow remains reticent to see the construction of another line that would bypass Russia proper. For years, the trans-Caspian line – much like the TAPI pipeline that would transit Turkmenistani gas to India – has appeared far more appealing on paper than on the ground. While the EU, Azerbaijan, and Turkmenistan have claimed the latter two are the only parties with required consent, Russia consistently cites environmental concerns and the Caspian’s uncertain status to stall any potential progress on the pipeline. And while there’s been some semblance of movement in delineating the Caspian’s status as a sea/lake, there’s no sign of a final status anytime in the near future. Nonetheless, European Commission Vice President Maros Sefcovic has said Turkmenistani fuel will reach EU customers by 2019; as such, barring a significant rapprochement between Ashgabat and Moscow, the most feasible route may well remain a trans-Caspian line.

Of course, the trans-Caspian line – which has helped repair strained relations between Baku and Ashgabat – could well be derailed by warming relations between Iran and the West. Likewise, Russia shows no signs of willingness to acquiesce in its Caspian military hegemony, despite recent buildups from the littoral states. As such, for the foreseeable future, Baku will continue having a leg-up on the rest of Central Asia. While Turkmenistan’s reliance only continues swelling vis-a-vis Beijing, Baku greets an eager Brussels with a wealth of gas that can help replace Russian supply. Whether or not the rest of Central Asia will manage to join Baku in serving the West the gas Brussels requires remains to be seen.