The year 2010 was a difficult one for U.S.-China relations. In January 2010, the Obama administration approved its first arms sale to Taiwan; Beijing cut off military-to-military relations in retaliation. Also in January 2010, U.S. technological firm Google publicly accused China of hacking its servers, sparking a high-profile recrimination from then-U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.

In mid-February 2010, Obama held his first meeting with the Dalai Lama since assuming office, causing more anger in China’s government and media alike. And in July 2010, the United States waded into the South China Sea disputes after Clinton gave a speech outlining Washington’s interests in the region at the ASEAN Regional Forum in Hanoi.

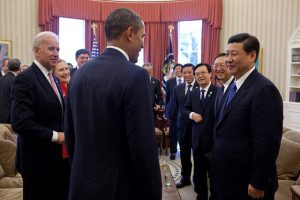

In other words, 2010 saw an outbreak of tensions in areas of intense friction between the U.S. and China: the Taiwan and Tibet issues, cyber issues (including internet freedom), and the South China Sea. Yet tensions cooled noticeably in late 2010 and early 2011, and the cause was clear: both sides were making a concerted effort to reboot their relationship in advance of then-Chinese President Hu Jintao’s January 2011 state visit (his first) to the United States.

Today, the U.S.-China relationship is in similarly dire straits. Many analysts believe, in fact, that the relationship is in its worst state in years, with structural issues (rather than discrete flashpoints) beginning to cause a rift in what has been called the world’s most important bilateral relationship. Most worryingly, there have been no signs to date that the tensions between Washington and Beijing are being brought under control in advance of President Xi Jinping’s upcoming state visit this September. That alone suggests how much the relationship has changed in just five years.

Unlike in 2010, when Washington and Beijing increased their outreach and began carefully shaping a successful narrative for Hu’s visit months in advance, tensions seems to be getting worse with Xi’s visit looming on the horizon. U.S. officials have told media outlets that the White House is seriously considering placing sanctions on China for alleged cyber crimes, specifically hacking attacks against private enterprises in the United States.

At the same time, many analysts (particularly those in the defense sector) are urging the Obama administration to give the Pentagon free rein to conduct “freedom of navigation” patrols within 12 nautical miles of certain reefs claimed by China in the South China Sea. Proponents of stronger action on the both the cyber and the maritime fronts argue that Washington should stop worrying about “upsetting” China and take concrete steps to defend its interests.

Those arguments tap into a deeper unease within the U.S. policymaking community that Washington has somehow been duped by China during the last 40 years of relatively stable ties. Analysts from Michael Pillsbury, author of The Hundred-Year Marathon, to Robert Blackwill and Ashely Tellis (in a recent Council on Foreign Relations report) argue that the U.S. strategy to engage China and integrate it into the world community has backfired and now must be abandoned.

Meanwhile, China itself is engaging in more anti-Western rhetoric than in recent memory, blaming “hostile foreign forces” (a shorthand generally understood to refer to U.S. agents) for protest movements in Hong Kong and Taiwan. Beijing has instituted new restrictions on NGOs and tightened supervision of universities and professors, citing concerns over the spread of “Western values.”

On the security front, China’s land reclamation and construction activities in the South China Sea have many U.S. analysts worried that Beijing’s ultimate goal is to militarize the region. Against the backdrop of growing U.S. concern over China’s military abilities and intentions, the optics of China’s military parade to celebrate the 70th anniversary of the end of the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression played particularly badly in American media and public opinion.

Given the litany of serious issues of disagreement – from cyber issues to the South China Sea to more long-standing areas of friction such as Taiwan, human rights, and the openness of China’s economy – the stakes are high for Xi’s visit to the United States. But the pessimism among policymakers and analysts on both sides seems to have preemptively overwhelmed Xi’s trip. Instead of discussions about progress in the relationship (as we saw in late 2010 and 2011, before Hu’s visit), the media narrative is dominated by negative stories.

In fact, there have even been calls for the visit to be downgraded or even cancelled altogether. Some U.S. analysts say Xi should not be “rewarded” with the pomp and circumstance of a state visit, while Chinese officials had allegedly threatened to cancel Xi’s trip if the White House implements cyber sanctions on China. Either the optics of the visit have truly spiraled out of control of both governments, or they are using the visit to increase – rather than decrease – tensions and up pressure on each other.

But there’s still time to salvage Xi’s visit. The ironic benefit of the negativity surrounding Xi’s first state visit to the United States is that the bar has been set quite low – any progress at all on seemingly intractable differences could be enough to turn the tide. Of particular interest are two important initiatives that have been overshadowed by larger structural concerns: progress on the U.S.-China Bilateral Investment Treaty and/or on an agreement to govern standard operating procedures when U.S. and Chinese aerial assets encounter each other in international airspace. With the 2015 UN Conference on Climate Change drawing ever closer, now is also the time to reaffirm joint U.S.-China commitments to and cooperation on battling climate change.

With U.S.-China tensions higher than they have been to date in the Obama presidency, it will be difficult for Xi’s visit to be a rousing success – but it’s more important than ever that Beijing and Washington can craft a positive narrative going forward.

This piece was originally published by Consensus Net. A Chinese-language version can be found on the Consensus Net website.