Kyrgyzstan may be looking for new partners to finance the construction of two major hydropower projects in the wake of years of delays and Russia’s declining economy.

Kyrgyz President Almazbek Atambayev, according to 24.kg, said during his year-end press conference on December 24, “I don’t like uncompleted construction projects, one should be realistic. We all see the state of the Russian economy, it is, shall we say, not on the rise, and for objective reasons, these agreements (on the construction of hydropower plants) can’t be implemented by the Russian party.”

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s press secretary, Dmitry Peskov, said that while there were difficulties with the projects different options were being considered. The Russian ambassador to Kyrgyzstan was similarly cautious, urging patience for an official statement from Putin and saying that the matter was not closed.

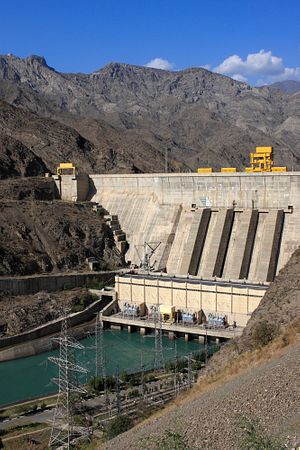

The two projects — the massive Kambarata-1 dam and the Upper Naryn cascade (comprising four smaller dams) — have been in various stages of progress for years. Eurasianet has followed the tangles, reporting in June 2014 that “Kambar-Ata 1 still appears to be in the dream stage.” In February 2015, Eurasianet reported comments from the Kyrgyz energy minister appearing in the Kyrgyz press that pointed to a lack of visible progress on both projects. “With Kyrgyzstan providing no cash or capital for either project,” Chris Rickleton wrote at the time, “it would not be a surprise if they are low on the Kremlin’s to-do list right now.”

In March, the Russian government approved the creation of a Russian-Kyrgyz development fund worth $1 billion. The Moscow Times wrote in March, “According to the draft bill, $500 million of capital for the fund will go straight from Russia’s strained federal budget to the fund’s account in the National Bank of Kyrgyzstan.” This infusion of capital was viewed as enticement for Bishkek to complete the accession process and join the Eurasian Economic Union — which it did, after several delays — in August.

Part of the current problems surrounding the two hydropower projects, however, seems to be the Russian-Kyrgyz development fund. Atambayev implied in his remarks that the Russians were hesitant to disburse funds because of worries of corruption in Bishkek.

“They thought that someone will steal money here. Apparently, they judged by the old standards. I explained that we have a different situation, and said: God forbid, you fought with corruption as we do. And we found mutual understanding,” he said, according to 24.kg. Atambayev noted that there were misunderstandings on both sides and even placed some of the fault on Kyrgyzstan for not seizing previous opportunities to make progress: “We have delayed allocation of land, didn’t use chance when there were money, when the Russian economy was booming.”

Days after Atambayev’s remarks, the development fund’s chairwoman, Nursulu Akhmetova, told a press conference that the fund plans to approve 26 large projects and 78 small- and medium-sized business projects in 2016. The few details reported pointed to “economy” housing construction and the importance of small- and medium-sized business.

The projects, worth over $3.2 billion, are a key part of Kyrgyzstan’s larger economic plan, which sees the small mountainous state exporting electricity to South Asia, in particular. Like Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan’s various hydropower projects are a bone of contention with Uzbekistan, which lies downstream and relies on water coming down from the mountains to sustain its massive cotton industry.