On the morning of January 14, a series of explosions and gunfire rocked the Indonesian capital of Jakarta, leaving at least seven dead and more than 20 injured.

While it is still early days, the evidence so far suggests that the so-called Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) is responsible. Though it is important not to exaggerate the significance of a single event, the attack highlights the growing reach of terrorists into Indonesia – the world’s most populous Muslim country – as well as the rising threat of militancy in Southeast Asia.

From what we know so far, the attacks began late Thursday morning in Jakarta when a suicide bomber detonated a device at a Starbucks, killing himself. Then, as individuals fled the café, two gunmen outside began opening fire, while two more suicide bombers detonated devices on the street. A Canadian man was shot dead and an Indonesian was killed by shrapnel, while the police shot and killed two other militants, leaving all five attackers dead. Police later said they had found six small bombs after sweeping the area.

The January 14 attack was hardly out of the blue. Indonesia is no stranger to Islamic militancy. A previous wave of terrorism following 9/11 saw Jemaah Islamiyah – loosely referred to as the Southeast Asian offshoot of Al-Qaeda – carry out a series of attacks, including the deadly Bali bombings in 2002 and twin bombings in July 2009 which targeted the J.W. Marriott and Ritz Carlton hotels. The 2009 attacks marked the last major terrorist incident in Indonesia. There are several groups currently operating in the country, including one based in central Java with links to ISIS as well as Mujahidin of Eastern Indonesia (Mujahidin Indonesia Timur, MIT) in Poso, Central Sulawesi, led by Santoso, who is Indonesia’s most wanted terrorist.

The threat posed by ISIS in particular had been rising towards the end of 2015. As it is, counterterrorism officials had estimated that over 500 Indonesians had gone abroad to join ISIS in the Middle East – including as part of Katibah Nusantara (Malay Archipelago Combat Unit) – with over 1,000 ISIS sympathizers in Indonesia. But not long after the Paris attacks in November, intelligence officials indicated they had evidence of an imminent attack in the country, with social media chatter picking up significantly. In December, Indonesian police arrested more than a dozen men across Java suspected of planning attacks over the holidays. And as I wrote just a day before the bombings, some experts had feared that ISIS would seek to target Indonesia in 2016 as one place in Southeast Asia to establish a territorial foothold (See: “Islamic State Eyes Asia Base in 2016 in Philippines, Indonesia”).

With the January 14 attack, Indonesia has experienced its first major terrorist attack since 2009. There are reasons to be concerned about what this all means. First, the fact that this was a coordinated gunfire-and-bomb attack with attackers at multiple locations rather than just one indicated some level of planning and sophistication. Thus far, Indonesian police have named Indonesian militant Bahrun Naim as the main person responsible for plotting the attack. Naim, who left Indonesia for Syria to join ISIS in 2014 after being jailed, is believed to be based in the ISIS stronghold of Raqqa, Syria, where he had been calling for attacks back in his home country. In one blog post entitled “Lessons from the Paris Attacks” (Pelajaran Dari Serangan Paris), Naim had encouraged Indonesians to study the specifics of those attacks – including the planning, targeting, and coordination. If this link holds up, it points to a rather alarming connection between Indonesian ISIS members in the Middle East and inspired militants at home.

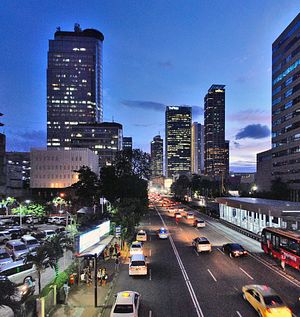

Second, while we still do not know the exact details, the location and targets suggest a rather bold operation. The attack took place not just in the Indonesian capital, but specifically on Jalan Thamrin, a busy street in Jakarta where a number of major hotels, malls, and office buildings are located. Furthermore, the attack appears to have begun with a suicide bomber at Starbucks. The choice of a Western symbol in incidents like these is rarely coincidental. Sidney Jones, a Jakarta-based expert at the Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict, had warned in November last year following the Paris attacks that with the rising ISIS threat, local militants may shift back towards targeting Westerners and soft targets as opposed to Indonesian police, who had been the main victims since 2010.

That said, some perspective is also needed when assessing both the attack as well as its broader significance. While the Jakarta attack was planned and coordinated, it was not as sophisticated as some of the attacks we have seen in the past, including the 2009 hotel attacks where bomb materials were gradually smuggled in by guests who checked in as paying guests days earlier. This attack was also largely a failure, with a relatively low death toll (five of the seven dead were militants). Though this is only one case, what we know so far suggests that these are local militants who are poorly trained. “It is the work of a new generation of radicalized militants, young and hungry to make an impact — but without the equipment and combat experience to carry out their wishes to the deadliest effect,” Yohannes Sulaiman, a prominent security analyst, concluded on the BBC website.

More broadly, as consequential as this attack is, it is important not to exaggerate the significance of a single incident. Indonesian security forces have been largely successful in foiling major plots in 2015, and their efforts even in this case had helped reduce casualties, which could have been far higher. Even before the attack, police had revealed on January 12 a more aggressive campaign in Poso to find Santoso – an important objective, since extremists have long viewed the area as a secure base and training center. One can expect these efforts to accelerate into 2016. And while it remains to be seen how the Indonesian government will fare against this growing terror threat, its tough response following the rise of Jemaah Islamiyah in the 2000s – which saw a degrading and disruption of violent networks in the country – offers some promise.

Jakarta’s resilience thus far following the attacks also needs to be credited. Following the attacks, people in Jakarta took to social media with a defiant message: “We Are Not Afraid” (#KamiTidakTakut), a hashtag which was trending on Twitter. Indonesian president Joko “Jokowi” Widodo also struck the right note in his initial remarks, expressing grief for the victims but also reinforcing the message that Indonesia would not be cowed

“Our nation and people should not be afraid,; we will not be defeated by these acts of terror,” he said in comments broadcast on local television.

The perennial challenge for the Indonesian security forces, of course, is that disrupting potential attacks and making arrests does not directly get at the ideology of ISIS, which is the source of its support in the first place. Without addressing that root problem, the existence of sympathizers and the prevalence of social media always risks giving rise to new ISIS-inspired attacks, and law enforcement officials may not be able to prevent all of them. After all, the sobering reality in combating terrorism is that law enforcement officials need to be right all the time to keep the country safe, while militants only need to be right once to spread fear necessary to achieve their political ends.