With a reemerging China in great power politics, instability on the Korean Peninsula, ongoing territorial disputes with Russia, and the rise of non-state actors, Japan is recalibrating its national security calculus at a time of changing dynamics in the Asia Pacific. The reinterpretation of Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution to allow for collective self-defense and the accompanying structural changes to the country’s institutional fabric gives rise to the notion that Japan’s military industrial complex is poised to come into its own. But how will Tokyo manage its transition to what the Abe administration has termed “proactive pacifism” amidst condemnation from neighboring countries, internal push-back from both rival and coalition political groups, and a citizenry largely conditioned in a culture of non-militarism?

To sell the image of a non-threatening Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) at home and abroad, important both in terms of domestic politics and international diplomacy, Tokyo has and will continue to utilize a web of affective cultural and entertainment resources – the Creative Industrial Complex (CIC) – to influence perceptions of Japan’s military establishment. The alignment between the CIC and the JSDF is nuanced, storied, and important for understanding both how Japan sees its own defense identity and how the international community sees Japan’s military.

The Manga Military

The CIC has produced a stunning amount of film, anime, theater, literature, fashion, and other expressive media designed to generate affinity towards the nation’s growing hard power identity and burgeoning military industrial base. Manga, perhaps chief among them and a multi-billion dollar publishing marvel, is an artistic iconography developed in Japan during the 19th century and long used by Japan’s political and government establishments as a potent marketing and communicative tool. In particular, the commodification of manga cuteness, often typified by extenuated character traits such as proportionally large eyes and small bodies, taps the power of “moe,” what Patrick Galbraith, author of The Moe Manifesto, describes as an affective response to fictional characters or representations of them – it is a cognitive or emotional reaction elicited from iconographic images.

Beginning in the early 1970s, state agencies, recognizing the strong commercial success of manga both at home and abroad, and the potential malleability of the moe that it engenders, collaborated with large corporations to produce manga that communicated political, business, literary, and educational information to the public. With this move towards cute, or kawaii, communication came a correlative change in how the Japanese citizenry digested their official information. This culminated in the production of a Manga History of Japan (Manga Nihon no rekishi) commissioned by the academic and literary publisher Chūō Kōronsha, a 48-volume work recognized by the Ministry of Education and Culture as an official educational resource for public schools.

By the mid 1980s, the use of manga as an official communicative medium had thoroughly permeated nearly all state-sponsored institutions save one – the Self-Defense Forces. Long shy of engaging with a highly critical citizenry and suffering from a poignantly negative internal and international public image, the JSDF had preferred to keep to itself, strategically slow in employing modern and non-traditional communication strategies. However, as economic hardship in the 1990’s reduced Japan’s relative power and influence, and a host of emergent foreign-born security threats reduced Japan’s absolute power and influence, it became clear to the JSDF and Ministry of Defense that answers to many important questions facing the nation would need to be answered with a more participatory defense establishment.

Thus, and as curtains closed on the Cold War theater, the JSDF and sister institutions sought to employ private sector creative industries to build avenues of information and knowledge flow to, from, and between the Japanese people and international community. With the launch of Prince Pickles, a cartoon and comic series that sought to describe the ideal “journey to peace,” and an initiative to publish official defense white papers in manga format for general consumption starring a character by the name of Ms. Future, the JSDF moved from a position of self-imposed isolation to one of active engagement. Strategically utilizing the then well-established and normalized popular culture of kawaii manga, the JSDF incorporated “cute” throughout its recruiting and public relations campaigns in what University of California professor Sabine Fruhstuck has described as a two track effort to pacify and negate its violent war-waging past and potential while also selling its role as a competent protector of Japan.

The popular AlphaPolis manga and anime series Gate perhaps best exemplifies the extent to which military-creative industry collaboration has become widespread since the turn of the century, as well as the changing manner in which Japan’s military interprets and represents itself. Produced, designed, and funded in coordination with the JSDF, the fantasy-based series glorifies Japan’s defense establishment with a doe-eyed cast of capable, identifiable, and non-threatening characters that protect Japan from alien invaders. As the plot unfolds, the youthful defenders of the nation’s sovereignty drive back the invading forces with the use of superior technology and, backed by the U.S. army, send a counter-invading task force outward to the place beyond the portal Gate on a quest for retribution. The story’s tracking with contemporary security-related issues and government agendas is unmistakable.

Cover art from the manga Gate, depicting Japan’s affable and attractive heroines

The utilization of moe by Japan’s manga military represents a poignant example of how postwar Japan negotiates the contentious process of normalizing its armed forces. It is precisely moe’s divergence from reality that allows it to serve as a familiar, affective lubricant in showcasing Japan’s JSDF and Ministry of Defense to a kawaii-primed public skeptical of its own armed forces and militaristic history. Moe induced by manga is the recognition of a fictional realism, whereby Japan is able to explore its hard power identity against a backdrop of cute fantasy, one in which the JSDF symbolically disarms itself by normalizing, domesticating, and emasculating the military. Indeed, the manga military has become virtually indistinguishable from many of the prominent “neighborly” government institutions, including the postal service, utilities, and railway, cast in their likeness from the same popular culture mold.

The Moe Ministry of Defense

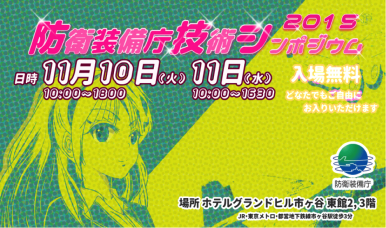

Although not much covered by mainstream media, Japan has embarked on a new approach to defense technology spearheaded by the recently established Acquisition Technology and Logistics Agency (ATLA) at the Ministry of Defense. The ATLA is tasked with core management functions concerning defense cooperation, R&D, and promotion of Japan’s indigenous high-tech industrial base: The organization is a central node in Japan’s growing military industrial network. Late last year, the ATLA hosted the annual Defense Technology Symposium for the first time, and as Crystal Prior notes for The Diplomat, a notably interesting aspect of the event was the use of manga/moe in showcasing and advertising the agency. From the gender, saucer-eyes, impish grin, determined brow, horizon-focused gaze, and professional attire, to the use of certain colors, textual highlights, and subliminal images imbedded in the tapestry background, this advertisement and those like it are highly nuanced approaches to message communication.

An advertising poster for the ATLA’s 2015 Defense Technology Symposium

While parsing images for meaning is a pursuit beholden to bias and subjectivity, a long history of findings in political and media studies have identified patterns in image recognition and propaganda methods upon which one may make certain conjectures. Here, the ATLA has followed in the footsteps of many JSDF showcasing techniques that utilize the manga medium. Female characters, for example, are often used in a bid to exploit prewar gender binaries of aggressive, kamikaze men and nurturing, supportive women. These kawaii heroines in advertising and images such at this remain motionless, neither in retreat nor in advance, symbolically indicating that they do not pose an immediate threat to the status quo. Eye contact and the primal challenge that it denotes is carefully avoided, with a gaze fixed on an unidentified point in the distance rather than directed at the viewer. Themes such as national pride, strength, or virtue are absent from the billing; the advertisement could easily be one for almost any product or service. Pink text with disco highlights reminds the audience that selling and buying weapons of mass destruction is only as unsavory as a night out in some of the more handbill-laden parts of Roppongi, the sordid nightclub district of Tokyo.

The American Macho Military-Entertainment Complex

One can find perhaps the most densely woven ties between the creative industries and government institutions in the United States, where Hollywood and the gaming industry work closely with the Pentagon in what Tim Lenoir and Henry Lowood of Stanford University have termed the U.S. military-entertainment complex (MEC). Similar to Japan, the MEC engages the public with fantasy-based iconography, although the form and function of the messages are vastly different. While Japan scripts a diminutive, temperate narrative of its self-defense force, the U.S. government embraces the hyper-macho, bazooka-blasting fare that defines the majority of military-related films and games. Washington is Tokyo’s closest and most important ally and has long pushed for Japan to take a more proactive, engaged roll in its own self-defense and regional affairs. As the Liberal Democratic Party and Abe administration continue to champion a recalibrated military mandate, recognizing the ties that bind the MEC to American identity offers an informative and juxtaposed comparison to Japan’s manga military.

The list of Hollywood movies produced with government support is hundreds of films long, and includes recent successful ventures Zero Dark Thirty and Lone Survivor. Perhaps the most endearing medium, however, has also been the most covert in connection: Films from the hugely popular animated and CGI-based franchises Iron Man, Transformers, and X-Men, which have been viewed, consumed, and internalized by a far-reaching domestic and international audience, have been developed and crafted in coordination with the Pentagon. In fact, the relationship is as old as the Oscars: the first Best Picture winner in 1929, Wings, a romantic action-war picture was produced in part by the U.S. government.

The military-entertainment complex creates economic and political advantages to both the U.S. government and Hollywood. Studios use taxpayer-subsidized military locations, personnel, and equipment in exchange for allowing the military script and / or final cut approval. This partnership enables entertainment companies to significantly reduced production budgets as well as source military establishment knowledge, while the Pentagon is able to harness the affective power of cinema to advance government agendas, and convert movie theaters, televisions, and computers into virtual recruitment offices and bastions of national identity.

Similar to Hollywood, many of the most commercially successful and technologically innovative games, including the groundbreaking and massively popular first person shooter (FPS) games Doom, Quake, and Counterstrike have been shaped and fashioned in various ways through formal collaboration between the United States military and the entertainment industry. The game premises of Call of Duty, currently the leading FPS game, track with contemporary conflicts and security threats, from nuclear proliferation to terrorism, pitting “good versus evil” gameplay under the watchful eye of the Pentagon.

The U.S. military establishment, similar to its counterparts in Japan, uses creative popular culture to shape domestic and international perceptions of its identity. As the U.S. continues to question its overall military posture, with increasingly vigilant domestic calls for a less interventionist foreign policy stance, one might expect to see a softer image put forward by the entertainment-military complex moving forward. If this sounds familiar to students of American history, perhaps it is because the Pentagon has used this tactic in the past at times of public discomfort with government foreign policy agendas, including during the Vietnam and Korean wars. Indeed, one of the most acclaimed action movies of the 20th century, the hit classic Top Gun, was produced in collaboration with the U.S. government, wrapping Ronald Reagan’s military adventurism in Libya and Grenada in a romantic cloak of brotherly love and national pride, complete with slick call signs and an infectious charismatic charm.

Opportune Kawaii Camouflage

Japan’s manga military engages in a potent form of political revisionism where it encourages the audience to rethink critical views of the military and government, and indeed the country’s history more broadly, by appealing to the familiar cultural and ideational ties of the creative industry. As Japan enters into its new era of “proactive pacifism,” Tokyo will continue to use the nation’s Creative Industrial Complex to (wo)man the helm of public perception both at home and abroad. Cute manga decals on fighter jets, missiles, and military establishment advertising campaigns will continue to mediate Japan’s changing middle-power consciousness. However, if the day comes when the JSDF and Ministry of Defense no longer must negotiate their identities with national and international perceptions, the disappearance of Japan’s kawaii-camouflaged manga military may well spell a turn to full normalization of the country’s foreign policy instruments and how Japanese society views its defense mandate in an anarchic world.

Matthew Brummer is a lecturer at Tokyo International University, researcher at Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, and Ph.D. candidate at The University of Tokyo. He tweets about technology, society, and international relations at @matthewbrummer