Western media outlets (such as the Wall Street Journal and The Economist) focused on the controversial security legislation Prime Minister Shinzo Abe pushed through the Japanese parliament in September. Yet Western media have paid far less attention to another significant change now well underway. In June of this year, legislation passed for the establishment of a new defense acquisitions agency under Japan’s Ministry of Defense. The new Acquisition Technology and Logistics Agency (ATLA) opened its doors for business on October 1.

The purpose of ATLA is to bring together disparate parts of the Ministry of Defense working on defense R&D, procurement, and exports under one roof. The goal is to improve efficiency, and eliminate organizational bureaucracy and duplication. Compared to similar agencies in Japan’s peer countries like the United Kingdom and France, ATLA is small, at 1,800 people and with a budget of about 2 trillion yen ($16.3 billion). Yet this is a massive agency by Japanese standards, representing a third of the total MOD budget. Creation of ATLA follows MOD’s shift away from the 1970 policy of indigenous development and production (former Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone’s kokusanka houshin) to its new “Strategy for Defense Production and Technological Bases.”

Japan’s Changing Defense Industry

The establishment of ATLA is closely linked to recent changes in Japan’s security policies, particularly the relaxation of its arms exports. The story begins in 1967, when Prime Minister Eisaku Sato established the “Three Principles on Arms Export and Their Related Policy Guidelines,” which prohibited arms exports to Communist countries, countries subject to arms embargoes under UN Security Council resolutions, and countries involved in or likely to be involved in international conflicts. Then in 1976, Prime Minister Takeo Miki strengthened these regulations to say that Japan shall not promote “arms” exports, regardless of the destination—creating an effective blanket ban on arms exports. These rules held for the four next decades, with the major exception of exports to the United States from the 1980s, most notably for collaboration on Ballistic Missile Defense.

In December 2013, Japan released its first-ever National Security Strategy, which promised to review the ban on arms exports. In April 2014, Abe’s Cabinet finally revised the Three Principles on Arms Export, even renaming them the “Three Principles on Defense Equipment Transfers.” The new rules allow exports in cases that will contribute to global peace and serve Japan’s security interests. Japan’s first deal under the new rules came in July 2014, when it sold Patriot Advanced Capability-2 (PAC-2) missile interceptors to the United States. Japan just lost its bid to sell its indigenous P-1 submarine hunting jet to the United Kingdom, but still on the table is a proposal to sell Soryu-class diesel submarines to Australia. Japan is also in talks with India about selling its US-2 amphibious aircraft.

Previously, people worked separately on defense acquisition from the Maritime, Ground, and Air Self Defense Forces, and also from MOD’s internal bureaus. The officials I spoke with when I visited the new ATLA office on November 12 said that currently, their greatest challenge is getting people from all these different areas and cultures to work together smoothly.

Besides integrating organizational cultures and understanding how to support defense exports, ATLA faces at least five other substantial challenges. One is how to achieve civilian oversight of arms procurement and exports. ATLA has an oversight arm of 20 people which monitors bid and procurement procedures and contact between officials and vendors. Yet Parliamentary oversight is basically nonexistent, even though as an advanced democracy, Japanese people should demand that their elected officials be involved.

A second challenge is how Japan will carry out adequate end-use verification of its defense technology exports given its intelligence limitations, both in terms of surveillance equipment and intelligence personnel. While arms exports to France, the United States, Australia, or the United Kingdom may raise little concern as these states have their own robust export control systems, exports to India, the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia, or Turkey present greater reason for concern.

A third major challenge is how ATLA will work with and through the new National Security Council when it comes to exports, and as well as with the ultimate licensing authority, the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI). The fourth and fifth challenges involve how to engage with an overwhelmingly pacifist public and still-hesitant Japanese businesses. Businesses are concerned about the public labeling them as “merchants of death” if they see their technology or goods used in warfare, and are looking to the government to take the lead.

Dual-use technologies present a way to address these final concerns, and ATLA should take advantage of the opportunity. As the only advanced country that has not made a major business out of exporting arms after World War II, Japan never developed the sort of military-industrial complex seen in the United States or European countries. Although Japan hasn’t exported arms, it is one of the world’s largest dual-use technology exporters—a known and recognized player in this field. Its peer countries are making the slow and sometimes painful shift from “spin-off” (transferring defense technology to the civilian field, as was done with the Internet or the microwave oven) to “spin on” (where militaries adapt civilian technology for their own purposes; Japan provided an early example of this with its low-power CMOS chips in Seiko wristwatches). Indeed, much of the technology and all of the talks at the recent Defense Technology Symposium featured such dual-use or spin-on-ready technology.

Showcasing Japan’s Defense Technology

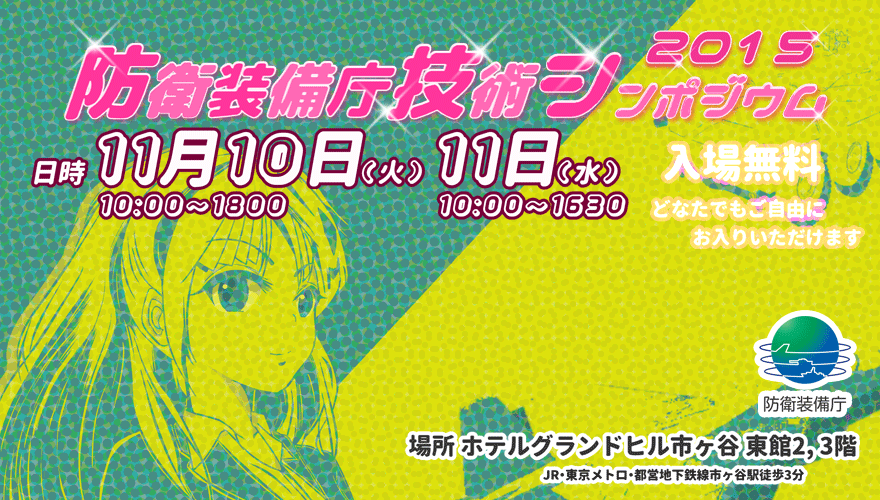

Hosting the annual Defense Technology Symposium was one of ATLA’s first tasks. Free and open to the public, it was held from November 10-11 at the Hotel Grand Hill Ichigaya, a Japan Ministry of Defense (MOD) Hotel. The most striking part of the symposium was perhaps this “Moe”/manga character–themed poster:

This year’s advertising and website stand in stark contrast to the blasé approaches of previous Defense Technology Symposiums (e.g., 2012, 2013, and 2014).

The apparent intent of this design was to make the event more attractive to the public, including students, and to impress upon the public that ATLA does more than just make weapons. Indeed, the four featured talks were: the Cabinet Office on its five-year Science and Technology Basic Plan, JAXA (Japan’s space agency) on supersonic aircraft and high-altitude UAV research, a professor at Japan’s policy research university on the importance of dual-use technology policy, and a professor and a corporate representative on the future of artificial intelligence and artificial cognition. These softer, policy-related topics garnered much interest. The dual-use policy session I attended was standing room only in the main hall, which held at least 300 people. Of course, there were also more military-focused presentations by Ministry of Defense officials, such as on Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear (CBRN) threat evaluation and the P-1 maritime patrol aircraft. (Read about more technologies that were covered here.)

The ATLA technology strategy head who concluded the symposium commented that they had about a 10 percent increase in attendance from last year. About half the people attending were from corporations and the rest from universities and research institutions. Another ATLA official confirmed via email that this year the symposium had 2,456 attendees over the two days, compared to 2,236 in 2014.

The symposium spread out over two floors in the hotel and had exhibit rooms featuring air, sea, and land technologies. Each of these rooms had poster sessions and booths with men (in the standard Japanese uniform—business suits) standing by to explain. A few Japanese companies also presented their wares, such as the virtual reality technology I got a chance to try:

Rather than focusing on purely technological sales like the US-2 or the P-1, ATLA should put as much or more emphasis on spin-on, which is truly the future of defense and the arms industry. Japan has demonstrated expertise in the dual-use field; the public is enthusiastic about Japan and its maintaining its technological advantage; businesses know the drill (unlike the governments’ clumsy start to the bidding process in Australia); and rigorous dual-use export controls under METI are in place.

It will be some time yet before we can evaluate how ATLA functions in the context of the recent policy and regulation changes. ATLA needs farsighted leadership to continue rationalization of Japan’s defense technology development, procurement, and exports. In the short-to-mid-term, ATLA would be well-served to focus and play up its contribution to spinning on the latest in Japanese advanced technologies.

Crystal Pryor is a resident Sasakawa Peace Foundation Fellow at Pacific Forum CSIS.