Last fall, Chinese lighthouses began operating on the reclaimed Cuarteron and Johnson South reefs in the South China Sea’s disputed Spratly Islands. Observers worried that China would use the new infrastructure to bolster its legal claims and authority over the area. But in February, when the Center for Strategic and International Study (CSIS) revealed that China had also built what appear to be advanced radar installations on those reefs, the legal concern shifted to a military one.

Gregory Poling of the Center’s Asian Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) told the Washington Post that the apparent High Frequency radar on Cuarteron Reef, especially, was critical to a “Chinese anti-access area denial strategy that sought to reduce the ability of the U.S. to operate freely in the South China Sea.” However, while China’s new radars are a serious new capability, it is not clear how they would inhibit U.S. operations except in an open military clash. Nor is it clear in that scenario that these sites could even survive for very long. Instead, the United States should consider that China’s radars in the Spratlys are likely far more important to cementing its civil control than directing its navy and air force.

Why does “High Frequency radar” merit so much interest? In the Cold War, over-the-horizon High Frequency (HF) radar systems were deployed by both sides to provide early warning of masses of nuclear-armed bombers or missiles closing in from across the ocean.

High Frequency (HF) waves are actually much lower than frequencies used by the radars carried on ships and airplanes, which typically use the Ultra- or Super-High frequency bands. Those lower frequency radio waves lose less energy as they travel through the air, allowing them to reach much farther distances. The tradeoff is that HF waves also carry far less precise information than navigation or targeting requires. HF surface wave radars may have ranges out to 200 nautical miles, and other HF radars can bounce signals off the lower atmosphere back towards the earth and detect ships and aircraft over 1500nm away.

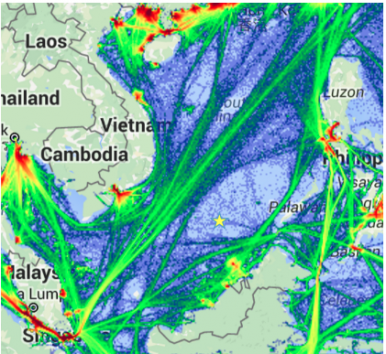

Even without more specific information about the apparent HF radar on Cuarteron (in concert with the constellation of other Spratly radar sites AMTI identified) it is possible that this radar system can cover the entire South China Sea, and almost certainly the entirety of the Spratly chain.

But when the Chinese Foreign Ministry announced the lighthouse groundbreaking on Cuarteron reef last May, there was no mention of a radar or communications complex. The lighthouse was justified on the grounds that “the South China Sea is a vital passage for maritime transport and one of the important fishing grounds in the world. A large number of vessels pass through this area, which is under complicated conditions and vulnerable to marine accidents”. Furthermore, China argued that the new facility would “provide passing vessels with efficient guidance and aiding services which will substantially improve navigation safety in the South China Sea.”

The Foreign Ministry reiterated this safety-of-navigation narrative when the lighthouse became operational that October, calling the South China Sea “an important maritime corridor, as well as one of the world’s major fishing grounds, with high density of vessels and complex sea conditions”, where the new lighthouse “will provide highly effective route guidance and navigation aid to vessels passing these waters.”

Much like the carefully crafted statements Chinese officials use to keep China’s other regional claims ambiguous, the Foreign Ministry’s comments about the South China Sea and its lighthouses are accurate but obscure the facts on the ground. The South China Sea is full of navigationally challenging waters and the Cuarteron lighthouse is on the south western edge of a 50,000 square mile area of the Spratlys most nautical charts label “Dangerous Ground.” U.S. Navy navigation guidance warns this area is “known to abound with dangers” and that “no systematic surveys have been carried out…and the existence of uncharted patches of coral and shoals is likely.”

The new lighthouse would thus be a valuable navigational aid if the area around it were not already devoid of commercial shipping. Cuarteron’s lighthouse has an advertised range of 22 nautical miles (nm). The main transit lane for ships traveling to and from the busy Malacca Strait is over 120nm away, and even smaller regional traffic does not get closer than 70nm. It appears that the only vessels that will ever see the Cuarteron light are small regional fishermen and Chinese vessels re-supplying the radar and communications infrastructure China has built around it. It is those regional fishermen, not the U.S. Navy, that may actually be the radar’s real target.

China is willing to do little more than object when U.S. warships patrol the South China Sea, but quite willing to use its Coast Guard to intercept other countries’ fishermen in the Spratlys and even to disrupt foreign maritime authorities from enforcement actions against illegal Chinese fishermen. HF radar coverage in the Spratlys could be a major new enabler of this aggressive “White Hull” strategy against other regional fishermen and law enforcement. Ironically, the United States has already modeled how such a maritime surveillance-enforcement scheme could work. After the threat of Soviet bombers subsided, the U.S. Navy’s East Coast HF over-the-horizon radar facilities switched their focus to assisting law enforcement by finding and tracking drug smugglers.

Unlike the massive Cold War HF radar installations that gazed across oceans from safely inland, facilities on the tiny, isolated reclaimed Spratly features would be vulnerable to quick neutralization in an actual armed clash. That vulnerability on its own suggests that, consistent with President Xi’s pledge against militarization in the Spratlys, these radars could be intended for primarily civil—not military—use. The outline of China’s 13th Five Year Plan revealed in March at the 12th People’s Congress included plans for a new national maritime strategy to “safeguard national maritime rights and interests, protect marine ecosystems and habitats, and open up more space for the blue economy so as to strengthen China’s maritime development.” In the heavily contested South China Sea, this is a tall order—one the Cuarteron HF radar could help China’s Coast Guard fill.

Steven Stashwick is a writer and analyst based in New York City. He spent ten years on active duty as a U.S. naval officer with multiple deployments to the Western Pacific. He writes about maritime and security affairs in East Asia and serves in the U.S. Navy Reserve. The views expressed are his own. Follow him on Twitter.