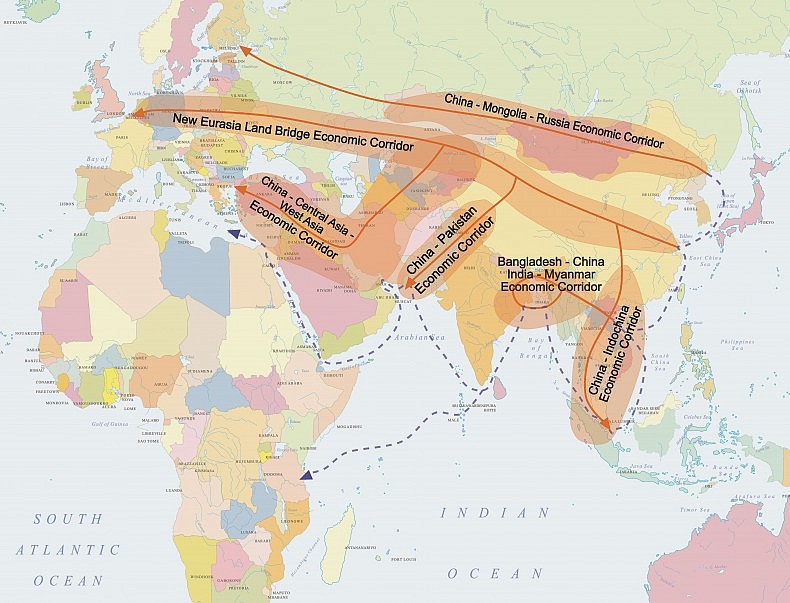

China’s “One Belt One Road” initiative clearly reads as an audacious vision for transforming the political and economic landscapes of Eurasia and Africa over the coming decades via a network of infrastructure partnerships across the energy, telecommunications, logistics, law, IT, and transportation sectors. While such themes have become the subject of intense debate and expert commentary in the past couple of years, one of the Belt and Road’s core “Cooperation Priorities,” that of “people-to-people” connections, has passed largely unnoticed outside China. Where it is discussed, it tends to be vaguely accounted for as China’s “soft power” strategy, an analytical approach that misses the complex role culture and history play in the initiative. To illustrate this, I focus here on the theme of heritage diplomacy in order to suggest that histories of silk, porcelain, and other material pasts, together with competing ideas about civilizations and world history, will play a distinct role in shaping trade, infrastructure, and security within and across countries in the coming years.

One Belt, One Road has been described as “the most significant and far-reaching initiative that China has ever put forward.” Five major goals sit within a broad framework of connectivity and cooperation: policy coordination; facilities connectivity; unimpeded trade; financial integration; and people to people bonds. Although this final goal is broadly recognized as an important mechanism for deepening bilateral and multilateral cooperation, it has received less media and expert attention in large part because its projects do not carry the spectacle of multi-billion dollar infrastructure investments and contracts, or the mega-project outcomes they produce. However, for both China and many of the countries involved, in cultural and historical terms, much is at stake in this project. As Xi Jinping indicated in his speech to the Boao Forum for Asia Annual Conference in 2015, the Belt and Road will “promote inter-civilization exchanges to build bridges of friendship for our people, drive human development and safeguard peace of the world.”

In recent years a growing number of experts have pointed to the role deep history plays in China’s conduct of international affairs today. The Chinese government is investing significant resources to connect present society to its past by establishing museums, expos, festivals, and countless intangible heritage initiatives. Perhaps most significant here though are its urban, monumental, and archaeological cultural properties, 34 of which are recognized by Unesco as being of Outstanding Universal Value and thus worthy of its prestigious World Heritage List.

Now in its fifth decade, the list has inadvertently become a marker of not just national, but civilizational standing. States around the world are pursuing world heritage status in order to promote particular forms of cultural nationalism and civic identities at home. At the international level, it has emerged as the cultural olympics of history, with much energy going into ensuring the worlds of European, Persian, Arab, Indian, or Chinese pasts are given the recognition they deserve. China ranks second in the global league table of listed properties, and the Silk Road will help it eclipse Italy in the prestige stakes of culture and civilization.

As David Shambaugh has indicated at length, culture has become an important pillar within China’s strategy to secure influence internationally, as was laid out at the 2011 plenary session of the 17th Central Committee of the CCP. Nowhere is this effort more important than within the region itself, where there are deep seated suspicions about China’s economic and military rise. I would suggest that it is within this wider context that we need to situate the Belt and Road strategy of fostering people-to-people connections.

But we also need to also look to the ways in which a historical narrative of silk, seafaring, and cultural and religious encounters opens up a space for other countries to draw on their own deep histories in the crafting of contemporary trade and political relations. Iran, Turkey, and the Arab States of the Persian Gulf are among those looking to the Belt and Road as an expedient platform for not only securing international recognition for their culture and civilizations, but also using that sense of history to create political and economic loyalty in a region characterized by unequal and competing powers. The now conventional idea of soft power focuses on how states and countries secure influence through the export of their own social and cultural goods. But this idea only partially captures what is at stake in One Belt, One Road. Reviving the idea of the silk roads, on both land and sea, gives vitality to histories of transnational, even transcontinental, trade and people-people encounters as a shared heritage. Crucially, it is a narrative that can be activated for diplomatic purposes.

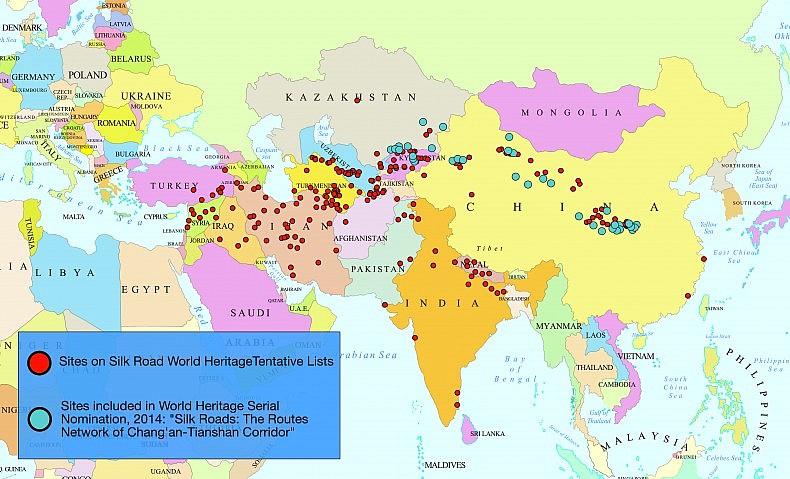

We are now seeing a surge in Silk Road nominations at Unesco’s annual world heritage committee meetings, with the Belt and Road dramatically changing the political impetus for cultural sector cooperation. The first successful Silk Road world heritage listing in 2014 involved government departments and experts from China, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan cooperating over 33 separate sites; the governments of Japan, Norway, and South Korea provided financial support. In November 2015, the 14 member countries that currently make up the Silk Roads Coordinating Committee gathered in Almaty, Kazakhstan to plan future nominations and tourism development strategies. Given dozens of Silk Road corridors potentially linking more than 500 sites across the region, the Silk Road is likely to emerge as the most ambitious and expansive international cooperation program for heritage preservation ever undertaken.

Interestingly, these Silk Road heritage nominations align with the multilateral structures of cooperation proposed under the “Vision and Actions on Jointly Building the Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road” issued by the Chinese government in early 2015. A proposed South Asian Silk Road nomination largely corresponds with Belt and Road’s Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar (BCIM) Economic Corridor, and plans for a Central Asian heritage corridor involving Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan directly align with the China-Central Asia-West Asia Economic Corridor.

This emphasis ties into the security dimensions of the Belt and Road initiative. One of the lessons of the original Silk Road was that cross border trade and cultural exchange build mutual respect and trust. Beijing places paramount importance on the stability of its western provinces. Transforming Urumqi and Kashgar in Xinjiang into commerce, tourism, and transport hubs, with the wealth generation that affords, will integrate the Muslim Uyghur communities of the region with the rest of the nation. Indeed, the recent history of Tibet and Lhasa provides a likely template of the cultural politics in play here. As cross-border and domestic tourism brings business opportunities to these regions it is highly probable that Han Chinese migration into the area will also increase. Moreover, for Beijing and the governments of Central Asia the specter of Islamic fundamentalism demands policies that that turn long, and in many cases porous, borders from a threat into an opportunity for creating the types of social stability that come from economic prosperity.

For many in the region, the Silk Road is a story of peaceful trade, and a rich history of religious and harmonious cultural exchange. The Belt and Road seeks to directly build on this legacy. It rests upon a historical narrative that connectivity — both cultural and economic — reduces suspicion and promotes common prosperity, an idea that is being eagerly taken up by states concerned about civil unrest, both within and across their borders. In November 2015, Nursultan Nazarbayev, president of Kazakhstan, chose UNESCO’s headquarters in Paris to announce the country’s new Academy of Peace, stating that “we can best counter extremism through inter-cultural and inter-religious dialogue.”

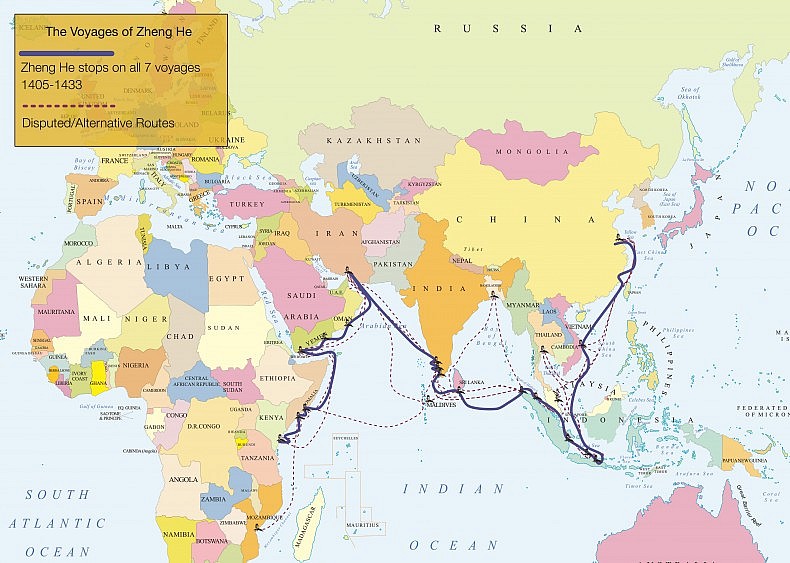

The situation of the overland Silk Road is mirrored in the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road. The 2015 Visions and Action plan calls for two transboundary maritime economic routes, linking deep water ports across the South China Sea, Indian Ocean, and beyond. It has been extensively documented that both China and India are competing to build networks of maritime infrastructure across these regions, amid growing anxieties over freedom of navigation rights and the need for strategic access for seaborne trade. Against this backdrop sits heritage diplomacy, with China and India assembling countries in the region for maritime-themed world heritage nominations, namely the “Maritime Silk Road” and the India-led “Project Mausam” respectively.

One figure in particular, Admiral Zheng He, embodies China’s grand narrative of region-wide trade, encounter, and exchange. A Muslim eunuch who led seven fleets across to South Asia, the Arabian peninsula, and West Africa between 1405 and 1433 during the Ming dynasty, Zheng He is widely celebrated as a peaceful envoy in both China and by the overseas Chinese living in Malaysia, Indonesia, and elsewhere. In addition to the museums, mosques, and artefacts now appearing around the region celebrating his voyages, China has given millions of dollars to Sri Lanka and Kenya to support the search for remains of Zheng He’s fleet. Both countries are key nodes in the modern-day Belt and Road infrastructure network, with China financing the construction of deep water ports in Colombo and Hambantota in Sri Lanka, and Lamu in Kenya.

In 2005, Singapore also celebrated the 600th anniversary of Zheng He’s voyages, hosting multiple events over the course of the year. These helped raise public awareness about Singapore’s maritime history and connections to China; an historical narrative political leaders now explicitly invoke to garner domestic support for Singapore’s strategic engagement in Belt and Road. Given the networked nature of the initiative, over the coming years we will see other states in the Persian Gulf, East Africa, and South-Southeast Asia excavate — both physically and discursively — their own maritime pasts and build heritage industries and museums around stories of trade, connection, and exchange.

By speaking to the construct of the Silk Road, One Belt One Road sits on a deep history of cultural entanglements and flows, which countries across Eurasia and beyond can buy into and appropriate for their own ends. As a bridge, this complex trans-boundary cultural history is reduced to a series of heritage narratives that directly align with the foreign policy and trade ambitions of governments today.

The Silk Road is a story of connectivity, one that enables countries and cities to strategically respond to the shifting geopolitics of the region and use the past as a means for building competitive advantage in an increasingly networked Sino-centric economy. Culture forms part of the international diplomatic arena now, and with routes, hubs, and corridors serving as the mantra of the Belt and Road, countries will continue to find points of cultural connection though the language of shared heritage in order to gain regional influence and loyalty. In both its land and sea forms, the Belt and Road gives impetus to a network of heritage diplomacy that fosters diplomatically valuable institutional and interpersonal connections. Perhaps more significantly though, this in turn provides the foundation for the more informal people-to-people connections that will lie at the heart of Silk Road tourism.

China has allocated $40 billion to the Silk Road Fund. The question remains how much of this will be dedicated to culture and people-to-people bonds more broadly. One Belt, One Road has been interpreted as a rising China sharing its economic wealth, and the load of building the infrastructure of an Asian century, with its regional counterparts. But it is important we also recognize that the project is built on certain ideas about shared, connected pasts that are doing important political work in creating forms of alignment, trust, and trade today.

Tim Winter is Research Professor at the Alfred Deakin Institute for Citizenship and Globalisation, Deakin University, Melbourne.