It has emerged that the Orlando shootings were committed by an American citizen whose parents emigrated to the United States from Afghanistan. Omar Mateen pledged support to the Islamic State (ISIS) shortly before his death, though he does not seem to have been actively recruited by ISIS.

While the motives for the attack have not been completely established beyond doubt, given that the attacks took place at a gay nightclub, it is likely that at least partially, the attacks were motivated by homophobia. Further details on the nature and motivation of the attacks can be found at multiple locations.

However, undoubtedly, there is now widespread interest in what Islam and Muslim-majority cultures say about homosexuality and the traditional manner in which homosexuality is approached in Muslim-majority societies, in particular Afghanistan.

As is the case with most Jewish and Christian understandings, virtually all schools (madhhab) of Islamic jurisprudence, Sunni and Shia, hold that homosexual acts are forbidden. The starting point for this view are the verses 7:80-7:81 of the Quran, which state:

وَلُوطًا إِذْ قَالَ لِقَوْمِهِ أَتَأْتُونَ الْفَاحِشَةَ مَا سَبَقَكُم بِهَا مِنْ أَحَدٍ مِّنَ الْعَالَمِين

إِنَّكُمْ لَتَأْتُونَ الرِّجَالَ شَهْوَةً مِّن دُونِ النِّسَاءِ ۚ بَلْ أَنتُمْ قَوْمٌ مُّسْرِفُونَ

We also sent Lut: He said to his people: “Do ye commit lewdness such as no people in creation ever committed before you? For ye practice your lusts on men in preference to women: ye are indeed a people transgressing beyond bounds.” (Yusuf Ali translation).

Most traditional Muslim clerics and scholars agreed on what this “lewdness” or “indecency” was. The classical Sunni commentator Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari (died 923) clarified that this referred to the practice of homosexuality. Sunni commentator Ahmad ibn Muhammad al-Thalabi (died 1035) and Shia commentator Abu Ali al-Fadl ibn al-Hasan al-Tabrisi (died 1154) both clarify that specifically the “indecency” referred to in the Quran is sodomy.

The Quran itself does not prescribe a penalty against homosexuals; however, usually the body of Sharia prescribes the death penalty for the act of sodomy based on the hadith (sayings) of Muhammad and the testimony of his sahaba (companions). Islam as a whole does not recognize any sexual act outside of marriage as legal, which excludes all homosexual activity in Islamic societies. However, the tradition does not endorse individuals taking the law into their own hands or attempting to implement the traditional penalties for illicit sexual activities in non-Muslim societies.

Penalties for homosexual acts are applied, as a consequence of this tradition, in many Muslim countries. Ten proscribe the death penalty, including Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. On the flip side of things, however, there is a fairly vibrant homoerotic tradition within Islam, and many Muslim societies ignore or find loopholes around Sharia.

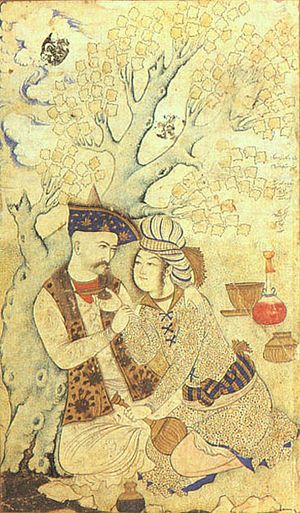

This tradition is particularly strong in the regions dominated by the Persian literary and courtly tradition, including much of today’s Iran and Afghanistan. The Persian tradition was filled with stories of love affairs and wine–and often these love affairs featured men with boys, a tradition that perhaps arose due to natural feelings or because codes of honor often limited the free interaction of men and women.

Several real-life rulers, such as Mahmud of Ghazni and the Mughal Emperor Babur, both based in Afghanistan for most of their lives, are recorded as having taking young male lovers and seem to have shown no interest in women, other than to further their dynasties. In his own memoirs, the only time that Babur seems infatuated about another person was when he fell passionately in love with a young boy he saw in the bazaar.

Persian poetry, popular also in Afghanistan, where Persian is the native language of about half the population (known as Dari), is quite often homoerotic. In sharp contrast to neighboring Urdu and Arabic poetry, until the 20th century, almost all love poetry in Persian is addressed from a male to a male. Persian poetry, often addressed to a “beloved,” usually addresses a boy (pesar, پسر).

In Afghanistan, especially Pashtun areas, the tradition of Bacha Bazi, which is Persian for “boy play,” is very common. It involves the use of boys for sexual pleasure by men and is very common, especially among men of power. Ironically, one reason why the Taliban was disliked by many of its enemies was because it tried to stamp out the practice.

Thus, Islamic attitudes and responses to homosexual acts vary greatly in practice and application, though there is not much variation among the legal schools of Sharia. Some countries, such as Turkey, simply ignore the Sharia as they are secular. Others, like Afghanistan, quite often apply their own laws selectively, leading to the tragic situation where while consensual homosexual relations are punishable by death, while exploitative relationships with boys are simply winked at. However, the presence of homoerotic themes in Persian poetry at least paints an alternative narrative of traditional attitudes to homosexuality than one might otherwise imagine from merely understanding the Quranic and Sharia views on the matter.