The 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) is supposed to be the constitution of the oceans because it establishes important principles on how ocean resources will be allocated and disputes settled. What the negotiators of the LOS Convention never anticipated is that two of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council would, in the case of the United States, not ratify the treaty, or would, in the case of China, disregard many of the most important features of the Convention including its dispute procedures.

China has made no bones of the fact that it regards the current arbitration case brought by the Philippines to be a legal nullity because of Beijing’s “undisputed” sovereignty of the features in the South China Sea (SCS). Yet China wrote and published in December 2014 a polished Western-style legal defense analysis of its positions. A decision by the Hague-based arbitration panel is expected in any day.

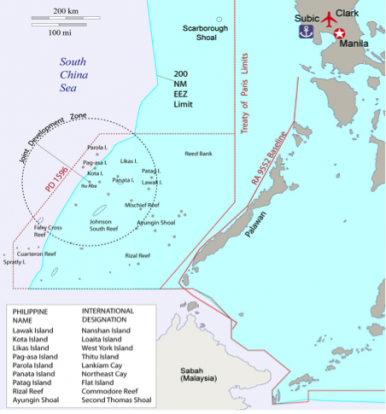

This case is a big deal. The Philippines is staking its rights to fisheries and oil and gas in these areas: Scarborough Shoal, Second Thomas Shoal (the site of a beached former U.S. Navy LST), Reed Bank (or Reed Tablemount – a hydrocarbon site), and eight features in the Spratly Island chain that are also claimed by Vietnam and the Republic of China (Taiwan). Regarding the eight features, the Philippines is claiming that most are low-tide elevations and that the PRC’s occupation of those features is illegal. Three other features, it alleges, are rocks and only entitled to a 12 nautical-mile territorial sea entitlement. Also under scrutiny is the legality of China’s assertion of its nine-dashed line claim to the South China Sea as depicted in China’s 2009 filing with the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS).

For its part, China’s asserts that its claims to the South China Sea are based on “historic rights” backed by imperial maps of the Ming dynasty and other historical documents. In successive legislative enactments in 1958 (territorial sea declaration), 1992 (territorial sea law) and 1998 (exclusive economic zone, or EEZ, and continental shelf assertion) China has asserted its sovereignty over the Dongsha (Pratas), Xisha (Paracels), Zhongsha (Macclesfield Bank and Scarborough Shoals) and Nansha (Spratlys) although it was never specific about the coordinates and extent of these claims. The Philippines lays claims to these same features (excepting the Pratas and Paracels) based on its legislative enactments, past occupation, and proximity to its mainland. Vietnam is a major claimant to the Spratlys and Paracels based on occupation and cession from France.

A final wrinkle in the overall equation is the claim of Taiwan to the 110 acre Itu Aba (Taiping), based on occupation since 1946 and possible transfer to Taiwan as part of the Japanese surrender documents. Itu Aba, given its strategic geographic location and the presence of potable water and some small-scale agriculture, gums-up the legal works since Taiwan could possibly assert entitlements to a 200 nautical-mile EEZ that would collide with the similar claims of the Philippines from its mainland. The difficulty with Itu Aba, and the claims of Taiwan, is that Taiwan has never formally petitioned to be part of the Arbitration; choosing instead to publish a persuasive legal manifesto on May 13, 2016 which chastises the Panel for proceeding without considering their interests.

Handicapping the outcome is complex given the recent oblique entry of Taiwan and, by extension, Itu Aba, into the fray. Some dismiss Taiwan’s statements as background noise since Taiwan is not a member state of the United Nations, or UNCLOS, and cannot formally intervene in an UNCLOS dispute settlement action. But under general international legal principle, so-called in statu nascendi, nascent states which are still in the formative stages, or are under the vestiges of some sort of colonial rule or legal disability, can receive limited judicial recognition and protection. The ICJ Opinion of 1971 Concerning the Occupation of Namibia is an example. It doesn’t help that Taiwan took so long to put forth a position. Were this case guided by common law, Taiwan might be estopped from making its arguments so late in the game. In the last analysis, the Tribunal will likely be able to avoid making any type of decision that directly undermines the interests of Taiwan to claim a full EEZ associated with Itu Aba. The lawyers for the Philippines have made it possible for the Tribunal to walk a fine line between legally classifying the characteristics of a particular feature versus indicating which state has the better claim of sovereignty.

Some analysts of this topic fail to appreciate the nuance of international legal practice, in which tribunals only decide the questions that have been put before them and do not “freelance” into areas which have not be raised by one of the litigants. In this particular case, the Philippines’ very talented legal team has been scrupulous in pleading the case in a limited way so that the tribunal is never asked to adjudicate ownership or sovereignty. But if the Tribunal were to rule that Gaven Reef, McKennan Reef (including Hughes Reef), Second Thomas Shoal, Mischief Reef, and Subi Reef are all considered low-tide elevations, then it must logically follow that China would have no right to occupy those features since low-tide elevations are considered part of the continental shelf (of either the Philippines or Taiwan) and are not subject to another state’s appropriation. (The question put forth on Johnson Reef, Cuarteron Reef, Fiery Cross Reef and Scarborough Shoal is whether these features are rock (or high tide elevations) or islands within the meaning of article 121 of UNCLOS. If a rock, they are entitled to a 12 nautical-mile territorial sea versus 200 nautical miles for a full-fledged island.)

At the end of the day, the arbitral panel is likely to rule that the five features listed above are low tide elevations and that Reed Bank and Second Thomas Reef are part of the Philippine Continental Shelf. The other listed features including Mischief Reef, Subi Reef and McKennan Reef (including Hughes Reef) will also likely be classified as low-tide elevations by the panel, but it will defer judgment on whether they are part of the Philippine Continental shelf because they could be within the EEZ of Itu Abu. They may, for example, in the case of McKennan Reef – which has been the site of a massive PRC reclamation project – declare that the PRC is without legal authority to occupy those features. The panel will also likely rule that Scarborough Shoal is a rock entitled to the 12 nautical-mile territorial sea and that the PRC has no authority to exclude Philippine fisherman from waters beyond the 12 nautical-mile territorial sea (but within the larger Philippine EEZ). The panel will probably not tackle the nine-dashed line matter since the PRC has never published the precise coordinates of that claim in its domestic law. However, the panel will probably issue an admonition that there is no legal basis for a state to claim a large swath of ocean based on a theory of historic rights. Put another way, historic rights might apply in general international law disputes over sovereignty over terra firma, but when it comes to rights over waterspace, UNCLOS is the single international law on this topic. Vague assertions of historic rights is not part of UNCLOS.

What Next?

James Kraska and other Western trained international lawyers are confident that that the Philippines will prevail on most questions. But, the question of “what next” from a legal perspective is much more elusive: Now that you have a judgment, what do you do to enforce the judgment? There’s no car or house to repossess. The political answer to this question seems straightforward in the short term: China has no choice but to claim that an adverse decision has no legal effect on them. They staked-out a legal and political position that the Tribunal had no jurisdiction and they are unlikely to publicly change that position Other states in the region and those committed to UNCLOS, will rightfully sound alarm bells that China’s actions are destabilizing both in terms of China’s relations with its smaller neighbors and in terms of the continuing viability of UNCLOS. For states that have tied their future to UNCLOS, it makes sense for them to increase the costs to China for engaging in legal revisionism since this particular case goes to the heart of what UNCLOS all about. Put another way, many maritime states outside of the region will not be comfortable with China being able to “cherry pick” the benefits of UNCLOS while evading its responsibilities as a member of the UNCLOS community.

Being a member of UNCLOS entitles members to have memberships in: (1) the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS); (2) the International Seabed Authority (ISA), and (3) to lodge petitions for the Commissions on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS). China has availed itself of those benefits and it would make sense for the tribunal, as a method of enforcing its decision, or a state party, to institute an action to deprive the PRC of the benefits of belonging to these entities. Specifically, there might be an action to recall China’s judge on ITLOS. The tribunal, or a state party could seek to block the CLCS from any further proceedings involving the rights of China in the current matter which are they deliberating vis-à-vis Japan and South Korea concerning seabed areas in the vicinity of the Okinawa Trough in the East China Sea. Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, China has at least two deep seabed mining applications which are pending with the ISA for prospecting sites in the Indian Ocean. It would be appropriate for a state (or the Tribunal) to argue to the ISBA that China should not be able to continue to pursue those claims (or serve on bodies that are writing the regulations for deep seabed mining) given their refusal to honor the decision of the arbitral tribunal in the Philippine matter.

The precise path to hold China accountable with UNCLOS institutions or compel China to cease reclamation or occupation via a court order is not clear. But most courts will declare that they possess “ancillary” jurisdiction to issue the orders necessary to give effect to their decisions and are binding upon states under UNCLOS 296.

UNCLOS Article 290 has a provision entitled “provisional measures,” which is vaguely similar to the contempt power of U.S. courts. In any event, the creative Philippine legal team could seek provisional injunctive actions against China in the above areas. Or, if the path of enforcement using the tribunal is unclear, the Philippines could petition the International Court of Justice for an order enforcing the tribunal’s decision since China cannot veto such a petition and the order would be legally binding upon China. The 1976 ASEAN Treaty of Amity and Cooperation has mandatory dispute provisions that possibly could be used to enforce the orders of the Arbitral Tribunal. (This is an interesting idea since China cited the ASEAN Treaty, among others, as a reason why the arbitral panel should not enter the case. ) Lastly, the Philippines, as a member of ITLOS, ISBA, and CLCS, could, as suggested above, simply petition that China’s access to these bodies be suspended so long as they are in “contempt” of the arbitration decision.

Students in the field of lawfare (in which China is quite expert and heavily invested) argue that quiet retaliation in the commercial law and trade field might be more effective than public legal action since it would create friction within China between its political leaders and its business leaders. Lawfare tactics used in the past include the threatened cancellation of a Russian cargo ship’s insurance, which resulted in that ship not transporting a cargo of arms to Syria in 2012. There were also lawsuits targeting banks in the Middle East to exact large financial awards (in court) against institutions that had previously held the deposits of international terrorists. Variations on these tactics might include increased inspections (and delays) associated with the entry of Chinese flag merchant vessels in the ports of certain countries, the non-recognition of its merchant ships’ insurance or inspection certificates, or the non-renewal of Chinese licenses to fish in the EEZs of other countries. Obviously, pursuit of these legal harassment measures could backfire and rob the Philippines of the moral high ground it has occupied by pursuing its grievances against China using legal means.

Before the Philippines pursues any of the listed provocative actions versus the PRC, it would be wise for it to press for the commencement of bilateral negotiations with China on access to the waters around Scarborough Shoals, Second Thomas Shoals, Reed Bank and, perhaps, some sort of joint use arrangement for the Spratlys. As regards the Spratlys, a joint development concept is something that both sides have endorsed and is a way to move the process forward. The Spitsbergen Treaty of 1920 (for Svalbard Island) is a good model: It involves all countries shelving their sovereignty claims but agree to share the oil and gas and fisheries resources on an equal basis. Figure 1 below depicts such a notional multilateral joint development zone agreement between the China, Taiwan, Vietnam, and the Philippines for the central Spratlys. The diameter of this zone could be increased to encompass more disputed territories.

Figure 1 Suggested Joint Development Zone

- A non-claimant state would be designated as the administrator (or trustee) over the zone. Indonesia, given its stature in ASEAN, may be suited to do this.

- All countries that have occupied high-tide features in the zone would be allowed to remain, although they would be required to replace all military occupiers with civilians. Military equipment would be removed.

- All structures built on fully submerged and low-tide elevations would be dismantled or converted to use by ASEAN researchers for biological diversity research purposes.

- The four parties would mutually agree to not assert territorial claims around any feature except that each occupier would have the right to establish 500 meter safety zones around each island/feature for safety of navigation purposes.

- The trustee would allow each of the four claimant states to fish anywhere in the disputed area and be the sole licensee of any fishing. Licensing would be based on current FAO standards to ensure sustainment of regional fishing stocks. Each one of the claimants would be entitled to 25 percent of the catch.

- Mining in the area would also follow the 25 percent formula.

- Oil and gas prospecting would be licensed by the Administrator on a strictly competitive basis. The 25 percent formula would be applied to any royalties received.

- The administrator would be the only state permitted to have permanently based military forces in the area to enforce the terms of the agreement.

- The United States, the EU and Russia would provide security guarantees to Indonesia in the event that any of its forces came under attack.

- The agreement would enter into force by agreement among three of the four countries and any outlier’s share would be held in escrow by the administrator.

For China to continue on its current trajectory as an economic and political power in Asia, it must realize that its power is inextricably linked to increased access to oceans near and far for resources and transit and that UNCLOS contains the rules for exploitation of that space and its resources. China seems to now be expressing some buyer’s remorse for not being more proactive when UNCLOS was being negotiated in the 1970s or in properly assessing the impacts when it joined UNCLOS in 1996. If China feels that UNCLOS does not protect their interests, then China would do well to pursue its long- term interests at the United Nations to seek amendments to UNCLOS and negotiate a short-term joint use arrangements like that suggested above as a holding action.

However, intentionally choosing a path that takes China outside of the UNCLOS framework and casts it in the role of Asia’s bully is neither in China nor ASEAN’s long-term political and economic interests. A naked win by the Philippines in the arbitration is a loss for everyone because turning China into a hardened legal foe does nothing to advance the cause of cooperation and diplomacy in the South China Sea. One can only hope that leaders in Manila, Beijing and other ASEAN capitals will come to this realization and take the next step to put the arbitration on hold so that negotiations in good faith can proceed, or else use its findings as the basis for a deal.

Mark Rosen is SVP and General Counsel at CNA Corporation. He also also holds an adjunct faculty appointment at the George Washington University School of Law. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author alone and do not represent the views of CNA or any of its sponsors.