Chinese President Xi Jinping made his second trip to Eastern Europe in 2016 this week, with stops in Serbia and Poland following a March visit to the Czech Republic. In all three cases, Xi took the opportunity to push for his European hosts to integrate into China’s “Belt and Road” initiative, which aims to link East Asia with Western Europe (and everything in between) via a network of interconnected infrastructure: rail, road, port, energy, finance, and telecommunications.

As The Diplomat has covered elsewhere, China under Xi has paid particular attention to the countries in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), even creating a new dialogue platform specifically for these 16 European states and China. Under the framework of the “Belt and Road,” these visits usually focus on discussions of the region’s (or a specific country’s) role in linking China with Europe — see the preferred phrase “China’s gateway to Europe,” which has now been applied to Poland as well as Greece, the Czech Republic, Belarus, and Romania.

As with the diplomatic framing, the type of projects as equally predictable: agreements in infrastructure (particularly railways), energy projects, and agriculture are the usual results of a visit to Europe by a Chinese leader. CCTV listed a number of pre-existing projects highlighted during Xi’s recent visit, all of which fit within that general rubric: “[T]he China-Europe land-sea express passage, freight train services between China and Europe, a rail link between Serbian and Hungarian capitals, the cross-Danube bridge in Belgrade, [and] the Kostolac power station in Serbia.”

During Xi’s visit to Serbia, officials and businesses from both countries signed 22 new agreements, including deals for China to finance a waste-to-energy plant, construct a highway in Belgrade, buy a steel plant, and conduct currency swaps. China also reportedly expressed interest in building a port and adjacent industrial zone on the Danube, which would echo similar projects along the Belt and Road.

In Poland, Xi’s visit led to the signing of 40 bilateral agreements, relating to construction, energy, and finance. Other deals will see increased agricultural and mining exports from Poland to China.

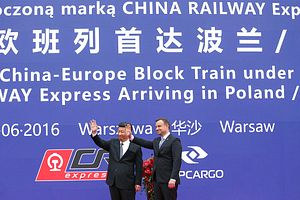

Xi also attended a special “Silk Road Forum” in Warsaw and, along with President Andrzej Duda, was there to welcome the first China Railway Express cargo train to the Polish capital. Further emphasizing the rail links between the two countries, CRI did a special report on an existing railway linking Lodz, Poland to Chengdu, the capital of China’s Sichuan province.

Also during Xi’s visits, China upgraded its ties with both Serbia and Poland to “comprehensive strategic partnerships.”

The theme of political – rather than economic — partnership was particularly strong in Serbia, which is not a member of the European Union. “Unlike some other Central and Eastern European countries, Serbia is not a European Union member. Because of a dispute with Brussels on the issue of Kosovo’s status, maybe it never will be,” Dušan Proroković, executive director of the Center for Strategic Alternatives in Belgrade, Serbia, wrote in an op-ed for China Daily. “[…]For the new strategic positioning of Serbia, China is in the long run probably the most important partner.

Meanwhile, Xi pointedly made the time to visit the site of the former Chinese embassy in Belgrade, which was hit by U.S. bombs during the 1999 airstrikes in Yugoslavia. Washington claimed the bombing – which killed three – was accidental, something Chinese analysts have never believed. The site is set to become a Chinese culture center; Xi attended the foundation-laying ceremony for what will become the “Serbia-China Friendship Square.”

The event was a silent (literally — Xi did not speak during the wreath-laying ceremony) rebuke not only of the embassy bombing in particular, but more broadly of what China Daily described as “NATO’s intervention in Yugoslavia.”

In a bit of irony highlighting the difficulties of China-Europe relations, even as Xi was being feted in Serbia and Poland, the European Commission issued a document expressing concern at recent developments in the South China Sea. While the policy document didn’t directly criticize China, its insistence on “freedom of navigation and over flight … in the East and South China Seas” and opposition to “unilateral actions that could alter the status quo and increase tension” were both read as implied critiques of Beijing’s policy.