Earlier this week, the Korea Coast Guard (KCG) reported that it opened fire on a Chinese fishing vessel fishing illegally in Korean waters near Incheon. The incident marked the first time the KCG fired its deck-mounted machine guns to compel non-compliant Chinese fishing vessels to stop and occurred after Korean officials vowed more forceful measures against illegal Chinese fishing in Korean waters.

According to the report, the episode took place during a standoff between the KCG and about 30 Chinese fishing boats operating near the Yellow Sea border with North Korea – an area of frequent encounters between Korean authorities and Chinese fishermen. After repeated warnings by the KCG for the Chinese vessels to stop, the Chinese vessels reportedly attempted to ram the KCG vessel, prompting the KCG to fire their machine gun into the air. The warning shots proved ineffective, so additional machine guns bursts were employed near the bow of the Chinese vessel. Two Chinese trawlers were seized in the clash and no one was hurt.

The incident comes on the heels of an earlier encounter near Socheong Island in October in which a small KCG patrol vessel was rammed and sank by a large Chinese fishing vessel as the Chinese vessel resisted arrest. Lee Joo-seong, head of the KCG’s central region, called the action by the Chinese vessel “attempted murder” and vowed stern action against the Chinese fishermen responsible. Reaction was swift from Korean lawmakers as well, with Rep. Woo Sang-ho, the floor leader of the opposition Minjoo Party of Korea, saying: “The violent, illegal activities by Chinese fishing boats are beyond a tolerable level. I would say they are not fishermen but pirates.”

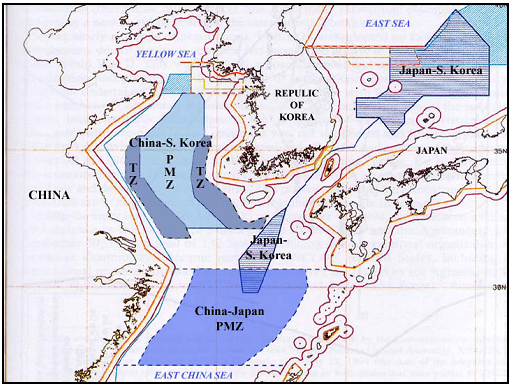

In response, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Geng Shuang said the KCG “should not have been operating in that part of the sea” because it was a “violation of the their joint fishing agreement.” He was referring to the 2001 Korea-China Fisheries Agreement. One notable feature of the agreement is that it provides for joint patrols of fishing vessels in a Transitional Zone (TZ) on each side of the Provisional Waters Zone (PMZ) in the Yellow Sea – an area of positive collaboration between the two countries.

Map: Agreed Fishing Zones of Sino-Japan and Sino-Korean Fisheries Agreements

Source: Xue, Gui Fang, “China’s Response to International Fisheries Law and Policy: National Action and Regional Cooperation,” Doctoral Dissertation, University of Wollongong, Center for Maritime Policy, October, 2004.

Under the agreement, each country’s coast guard personnel may board and inspect fishing vessels of both parties, and the flag state of each vessel is responsible for compliance with the terms of the agreement. The most recent joint patrol, for example, occurred in July of this year.

However, another important provision of the TZ is that fishing activities within the respective zones of the other country were to be phased out and gradually conform to the coastal state’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) jurisdiction. That has not occurred. In fact, Chinese fishing vessels have continued to fish in these zones with increasing frequency over the years, leading to violent standoffs between KCG and Chinese fishermen.

Even before these recent high profile incidents, illegal Chinese fishing had been a constant irritant between South Korea and China, leading to the deaths of both KCG officers and Chinese fishermen. In early October, a Chinese fisherman was killed during a scuffle with the KCG 90 miles west of Wangdeung-do island. In September, three Chinese fishermen died trying to evade arrest after KCG officials fired flares and non-lethal stun grenades into the vessel’s wheel-house where Chinese fishermen had locked themselves in. In December of 2010, a Chinese fisherman died while attempting to repel KCG officers from boarding their fishing vessel. Since 2008, two KCG officers have been killed by Chinese fishermen and 73 injured during attempted arrests of Chinese fishing vessels in Korea’s EEZ.

The KCG reports that Chinese fishing boats are now choreographing their movements in groups – often connected together with ropes – making it difficult for KCG vessels to approach and board Chinese vessels for inspection. Many Chinese fishermen also wield iron bars, pipes, hammers, shovels, knives and hatchets, according to KCG officials, making non-compliant boardings a particularly dangerous endeavor for officers.

This is not a localized trend in the Yellow Sea, of course. In other parts of the world, such as off the coast of Indonesia and Argentina, Chinese fishermen have shown an increasing willingness to challenge attempts by coast guards to enforce fishing laws in EEZs of coastal states, leading to several deadly confrontations.

In part as a consequence of Chinese illegal fishing, the KCG has embarked on a modest ship building program to procure nine vessels (eight 500-ton and one 3,000-ton) to support the Korean shipbuilding industry and strengthen maritime sovereignty and governance. Two Korean Shipbuilding companies were awarded contracts for the smaller sized vessels: Hanjin Heavy Industries & Construction and Kangnam Corporation. The wining contract for the 3,000-ton ship has yet to be announced.

Such clashes over fishing rights between China and South Korea will not greatly affect bilateral relations, but are nonetheless cause for concern among Korean lawmakers and officials who have long viewed Chinese fishermen as renegade mercenaries at sea. The clear winner in all of this may be a rejuvenated KCG, which was unceremoniously disbanded after the failed rescue operation during the sinking of the Sewol ferry in 2014. A focus on countering illegal fishing in Korean waters seems to be translating into greater budgets and renewed pride for the KCG.

Lyle J. Morris is a senior project associate at the nonprofit, nonpartisan RAND Corporation.