By any metric, Hong Kong’s skyline is a breathtaking testament to the city’s vast wealth. The city has a GDP above $300 billion and is home to Asia’s four wealthiest men, who own a combined net worth of $90 billion.

But beyond the dazzling lights, swanky dining, and luxury shopping, large segments of the city’s population are living in poverty — one in five, to be precise. Making matters worse are the city’s real estate prices, which are among the world’s most astronomical. This state of affairs has forced the city’s lowest income residents to accept inhumane housing conditions, from “coffin homes” to literally sleeping in cages.

Depressing housing conditions are nothing new in Hong Kong. After all, the infamous “city of darkness” was only demolished in 1993. During its heyday, the city-within-the-city housed 35,000 to 50,000 (varying by estimate) in an anarchic labyrinth of 300 interconnected highrises.

And the gap is widening. The South China Morning Post recently pointed out: “In the city with the highest number of Rolls-Royces per person, tycoons splurge HK$100 million on a wedding without batting an eyelid, or millions more on diamonds to name after their children, while some 300,000 kids can’t get three square meals a day.”

Add to this the reality that Hong Kong is home to at least 29,500 people — mostly domestic workers — who are essentially slaves, trapped in a system of forced labor that is among the worst in Asia.

Jonathan van Smit, a self-taught photographer from New Zealand, has been roaming the streets of Kowloon by night documenting this gritty side of Hong Kong since 2008. Jonathan spoke with The Diplomat about the unvarnished, yet human images he captures by veering far off Hong Kong’s well-beaten path.

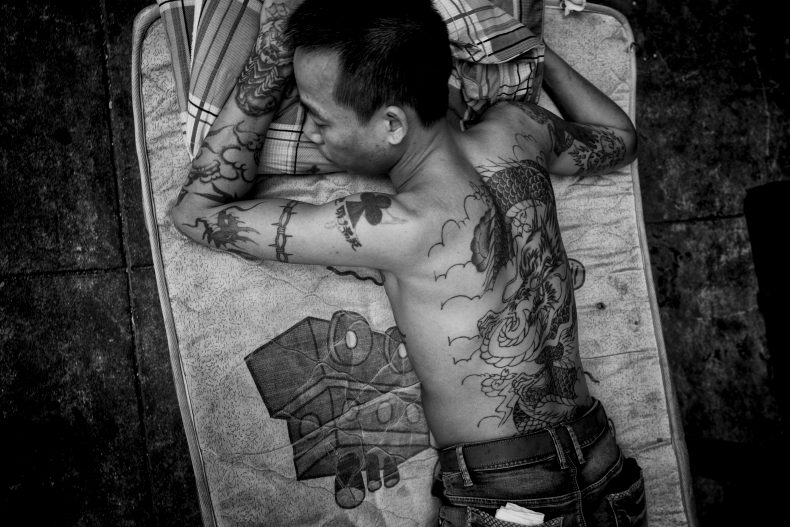

Man with the dragon tattoo, Hong Kong. Photo by Jonathan van Smit

The Diplomat: I’ve read that you moved to Hong Kong in 2008. Did you seriously start to take photos then? Or had you already been developing your eye before leaving New Zealand?

Jonathan van Smit: I was only taking travel snapshots in 2008-2009, and then began to become more seriously interested in photography in 2010.

Did you set out to create the style you have developed — i.e. stark black and white images, nighttime street scenes, the lives of impoverished people living on the fringes of society? Or did you come to discover your primary themes by simply roaming the streets of Hong Kong with a camera in hand?

I don’t really think about my photography that much. I simply began to play with contrast and black and white conversion so that a photo connects with me emotionally in some way.

I’m more interested in the actual taking of a photo than editing or processing. I love walking, which I do for hours on weekends… especially in more marginal areas away from city malls and highrise buildings. Daytime walks morph into night walks where there’s more mystery. It’s a different world when darkness falls.

I have gone on some long photo walks at night in Hong Kong, particularly in Kowloon, myself. So your work really resonates and inspires me on a personal level. What is it about Kowloon that draws you?

I was originally motivated by trying to find traces of mid 20th century Hong Kong as that heritage has been disappearing very quickly. Now, my main interest is exploring lives and worlds that are different from mine.

I love walking in Kowloon, especially those areas west of Nathan Road, because of its density, its history, and also partly because of its dystopian atmosphere which appeals to me. I’ve also occasionally done community work there, which provides a little insight into people’s lives there.

There have recently been stories in the media about “coffin cubicles, caged homes and subdivisions.” In the past, Hong Kong was also home to the infamous yet legendary “Kowloon Walled City” – aka “city of darkness.” Do you think there’s something about Hong Kong that sets it apart as an urban environment for the kind of street scenes and characters you feel most compelled to photograph?

Coming from New Zealand, and also growing up in rural U.K., the teeming density and street life in Hong Kong does seem remarkable but it has parallels in other large cities in Asia, for example, Chongqing, Kolkata, and Beijing. The difference with Hong Kong though is that I’ve been here for a few years now, and know my way around so I guess that makes it easier.

Cage Home TV Room, Mong Kok. Photo by Jonathan van Smit.

Has seeing the radical separation between the rich and poor up close and personal fundamentally changed your view of Hong Kong?

Sadly, the economic marginalization of a substantial proportion of Hong Kong’s population seems to have worsened since I’ve lived here. People in similar sized cities in mainland China now seem to have more opportunities and a better quality of living than Hong Kong, while that certainly wasn’t the case 10 years ago.

In particular, the opportunities for the younger Hong Kong generation seem to have diminished. Property prices have spiraled out of reach for many people, which leads to a feeling of hopelessness.

When you’re out with a camera in hand and you see something that want to capture, what sense or alignment of factors generally impels you to press the shutter button?

I know I should have a clever, arty answer to this question but really I don’t think much when I’m walking. It’s more about being open to circumstance, and letting intuition and instinct come to the fore. Most of the time, I don’t even use the viewfinder, and just guess the subject framing.

Drug use, the lives of sex workers, boredom, sadness, loneliness, neglect — your work explores some heavy themes. Do you think Hong Kong is any more full of these socioeconomic issues than other large Asian cities?

Hong Kong is one of the world’s wealthiest cities, has a sizable population of extremely rich and privileged people, and the gap between rich and poor is very obvious. It bothers me a lot, and sometimes even makes me angry. Of course, it exists in other cities such as Beijing and Shanghai but it doesn’t seem so obvious to me elsewhere as it does in Hong Kong.

Have you spent time photographing other large Asian metropolises?

One underlying theme that I like to explore is marginalization and how people react to adversity. I have visited other cities such as Kolkata, Beijing, Shanghai, Phnom Penh, Hanoi, Ürümqi and so on to take photos, and I’m instinctively drawn to areas that are away from city centers and big shopping malls.

Skinny preparing AK’s meth bong, Phnom Penh. Photo by Jonathan van Smit.

Do you ever feel in danger when entering some of Hong Kong’s rougher areas? And how do you get people comfortable enough to let you take their picture, often in very vulnerable situations and settings?

Hong Kong is a very safe city so I’m pretty comfortable walking around at night.

In the course of your exploration, have you met any certain individuals who have made a particularly deep impression on you personally?

Quite a few, and the strong impressions can be negative as well as positive. Just this weekend, I had a long chat with an alcoholic in his mid-fifties who used to be a tennis coach here in Hong Kong, and is now staying at a hospice for street-sleepers after suffering a serious knee injury. I was struck by his intelligence, optimism, and ability to smile and laugh despite the adversity he faces.

There’s AK, my fixer in Phnom Penh, who was once a boy soldier in the Khmer Rouge and now deals in hard drugs and women. He’s almost animal-like in his instincts and lack of morals but is also good company and often charming.

And then there’s the expat who was running an NGO in Cambodia who maintained that he was religious about financial transparency and governance but who was ripping off his donors. He’s the worst of the lot, in my view.

The deepest impressions though are from young women I’ve photographed, usually with a young child, whose lives and dreams spiral down into a hopeless pit of sex work, drugs and abusive men.

I read a comment describing your work, which you made in another interview that I found intriguing: “…it’s not documentary, it’s just a personal perspective, and sometimes veers off into the realm of fiction.” Can you explain a bit more what you mean by fiction here?

I was simply trying to make the point that I’m not trying to document anything. I’m certainly not documenting the lives of the people who appear in my photos. A photo is just a tiny slice in time, and often exists in another context than reality. I’m often surprised when a photo I’ve taken shows something which I hadn’t noticed at the moment of taking the photo, even it’s just a fleeting expression of sadness while laughing or smiling.

I’ve read comments you’ve made saying you don’t like to look at other photographers’ work all that much. But your comment about “fiction” makes me wonder: Do you draw inspiration from other art forms?

I think that was a comment made a few years ago because I do have a few photography books now. I prefer looking at paintings more than photos but I’m not sure if I’m particularly influenced by them.

Mong Kok alleyway. Photo by Jonathan von Smit.

If you were to take a radically different direction with your photography in Hong Kong, what is another aspect of the city that might spark your curiosity in a new way?

I’m not sure that I want to take a radically different direction in Hong Kong unless something here changes radically. I’ve spent the last four years exploring drug use in Phnom Penh, and that is an ongoing project. I’m also planning to visit the Philippines soon, and want to take photos in a small, rice growing community so I suppose that is a new direction. I also want to go to Dhaka in the next year or two.

Are you working toward some kind of exhibition/book/body of work that you would like to present to a wider audience in the future?

I’m far too lazy to put a book together! I haven’t even updated my website for three years.