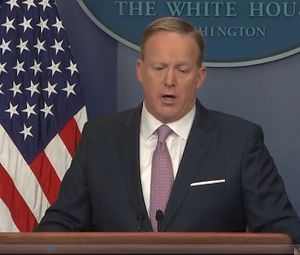

Roughly 72 hours since Donald Trump’s swearing-in as the 45th president of the United States, we got our first utterance from the new U.S. administration on the South China Sea — and it wasn’t entirely reassuring. Sean Spicer, Trump’s White House press secretary, fielded a question on the subject from a reporter during the administration’s first White House press briefing on Monday.

“The U.S. is going to make sure that we protect our interests there,” Spicer said, referring to the South China Sea. More specifically, Spicer had been asked if the administration stood by comments made by Secretary of State Designate Rex Tillerson during his confirmation hearing earlier in January. Tillerson was approved by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee shortly after Spicer’s press briefing. (I discussed Tillerson’s remarks on the South China Sea in some detail in these pages shortly after he made them.)

“It’s a question of if those islands are in fact in international waters and not part of China proper, then yeah, we’re going to make sure that we defend international territories from being taken over by one country,” Spicer added.

Spicer’s remarks will have been heard closely in Beijing and in the capitals of the other claimant states in the South China Sea. Unfortunately, they demonstrated a worrying lack of familiarity with both the status quo in the South China Sea and the work of the outgoing Obama administration in the region.

The incoming administration, of course, has every right to telegraph and execute a change in U.S. policy in the South China Sea if it so wishes, but it wasn’t clear if Spicer meant to signal as drastic of a departure with the Obama administration’s policy as his remarks make it seem. For instance, as I wrote after Tillerson’s remarks on the South China Sea:

The United States currently does not take a position on the sovereignty of individual features in the South China Sea. This is true even of features claimed, but not controlled, by the Philippines — a United States ally.

If Washington were to interdict China from accessing its possessions in the South China Sea without doing the same for the other claimants — a group including the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, and Taiwan — then it would be discriminating on the legitimacy of specific claims.

Though Spicer was somewhat more subtle than Tillerson in his remarks, the implication of his distinction between islands that are “part of China proper” and other islands suggests a divergence from Obama-era (and prior) U.S. policy in the South China Sea. Spicer’s use of the phrase “international territories” is particularly puzzling and he didn’t seem to raise the issue of South China Sea features occupied by other claimant states, including the Philippines, a U.S. ally.

Most notably, stating an intention to “defend international territories” could be read in the region as a sign that the incoming White House is serious about revising the conditions under which it would resort to force in the South China Sea. (The Obama administration’s threshold would likely have been a Philippine request to defend its Spratly possessions covered under the two countries’ Mutual Defense Treaty.)

The words “freedom of navigation” — the linchpin of Obama-era declamations on U.S. interests in the South China Sea — did not appear at the briefing, notably. Spicer could have easily described Chinese claims as “illegal,” but did not — a view that would be supported by last July’s decision by a Permanent Court of Arbitration-based tribunal.

Of course, these are early days, and it’s quite likely simply that Spicer, given the broad portfolio of the incoming administration, simply hadn’t been adequately briefed on the South China Sea issue. But more concerningly, Spicer’s answers demonstrate that the new administration simply doesn’t have a coherent policy for the region, which stands as one of Asia’s prime flashpoints and a hotbed of tensions between the United States and China in particular.

This would matter for any incoming administration, but matters especially for the Trump administration, which has telegraphed its intention to go head-to-head with China along several fronts — most notably over Taiwan and the One China policy, and trade policy.