The restructuring of Kazakhstan’s banking sector continued at full steam in the past few months, signaling the upcoming consolidation of major lenders in an effort to withstand the economic downturn and cleanse bad debt from their balance sheets.

South Korea’s Kookmin Bank said it will sell its 41.9 percent stake in Bank CenterCredit and leave Kazakhstan less than a decade after first setting foot in the Central Asian market. A group of investors led by Bakhytbek Baiseitov, CenterCredit’s chairman, and TsesnaBank, a medium-sized bank owned by Adilbek Dzhaksybekov, head of the Presidential Administration, came forward to buy the stake for around $780 million. The group of investors said it will also buy the 10 percent that the World Bank’s IFC had bought in 2008, to aid Kookmin’s takeover. Baiseitov already owns around 27 percent of CenterCredit.

Baiseitov, one of Kazakhstan’s richest men, could guarantee a smooth takeover of CenterCredit, which could be ultimately bought by TsesnaBank, thus strengthening its position as the third-largest bank in the country.

The exit of Kookmin Bank is a sign of market failure in Kazakhstan’s banking sector: in the past few years, international lenders have left the country, reversing their investment strategies of the early years after independence. Analysts said that Kookmin will pull out at a loss, chiefly because its shares in the Kazakhstan Stock Exchange were denominated in the local tenge currency, which has suffered four major waves of devaluation since 2008.

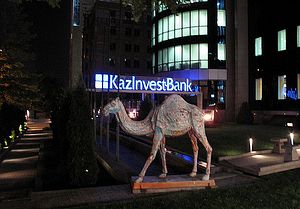

At the end of December, the Central Bank revoked KazInvestBank’s license because of its unsustainable holdings of non-performing loans (NPLs), or customer debt past 60 days overdue. For KazInvestBank, the ratio of NPLs over the total loan portfolio had grown to about 80 percent. This was the first time the Central Bank intervened to strip a banking license since 2006.

KazInvestBank, ranked as Kazakhstan’s 20th bank by assets, was linked to elite figures of the caliber of former ministers Nurlan Kapparov and Yerbolat Dossayev and businessmen Berik Kaniyev and Yuri Pak until mid-2016. As the bank was being stripped of its license, Gauhar Kapparova, the wife of late-Nurlan Kapparov, sold her 10 percent stake to Nurzhan Dzhanabekov, an associate of the former owners. Now, the bank is under administration and will likely be liquidated in the next few months.

In the meantime, the inactivity of KazInvestBank will put a strain on its customers and shareholders alike. Importantly, the administration of KazInvestBank will also have an impact, although marginal, on the Single Pension Fund, where the bank held around $9 million. This shows just how even minimal cracks in the financial system could affect the whole socio-economic structure in Kazakhstan.

Amid the malaise of smaller lenders, the Halyk Bank-Qazkom saga continues. The two banks, the largest in Kazakhstan, have been in merger talks for a few months. Halyk’s chairwoman, Umut Shayakhmetova, recently set a necessary condition for the success of the deal: Qazkom’s bad debts cannot be part of the merger.

“We have not yet signed a final document because the transaction is very complicated. My opinion is that the deal between Kazkom and BTA was not properly structured and the consolidation was not concluded correctly, which has created problems for Kazkommertsbank. Instead of isolating and mending, or simply writing off [toxic assets], Kazkom put them on its balance. This decision aggravated the quality of their financial assets,” Shayakhmetova told Forbes.

Kazkommertsbank, abbreviated as Kazkom in common parlance, was the former name of Qazkom, which rebranded in 2016 to reflect the new ownership after businessman Kenes Rakishev bought off its largest investors in 2014-2016. Shayakhmetova’s reference to the buyout of BTA, the former bank of fugitive oligarch Mukhtar Ablyazov, traces back the origin of Qazkom’s current problematic balance sheet to the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-08, which brought BTA to default on its toxic assets.

The regional economic downturn, paired with sustained low oil prices, has put enormous pressure on Kazakhstan’s financial sector, as customers have proven unable to pay back their debt and banks have continued to accumulate toxic assets. More than a policy choice, the restructuring of the banking sector seems a necessary process that Kazakhstan has to kick-start if it hopes to see the crisis through.