With work featured in Amnesty International, BBC, CNN, Freedom House, and China Digital Times, artist Badiucao challenges China’s Communist Party with the almighty power of the political cartoon, using Twitter to spread his distinctive images around the globe. Using a pen name to protect his identity and relations in China, Badiucao was born and raised in Shanghai and his work is currently being exhibited in “Home Thoughts from Abroad” for the Adelaide Fringe in Australia.

Credit: Badiucao

How did you get started drawing political cartoons?

I didn’t do any political cartoons back in China, only starting when I came to Australia. That’s when I felt safe enough to do things like that. But I started studying political cartoons on Weibo. The trigger moment was when there was a bullet train incident (the 2011 Wenzhou train collision), and at the time it was the biggest news on Weibo, and I wanted to comment on it with my own voice. I’m not really good at writing things, so I thought visual language was the comment I should make; that’s how I started my political work. But, as you know, Weibo in China was being controlled day by day and I had to constantly recreate my account because it got deleted all the time. I had to move to Twitter […]

For me, political cartoons are a form of self-expression, I mean, everyone should have a voice, have an opinion, on what is happening in China and this is how we can comment and criticize. I think that, in China, every incident has a uniform, united, or official way to explain it, but it will never be good enough to tell the truth, to tell the facts. I believe that individual perspectives contribute to society, and I want to contribute with my perspective with visual art. I also think that political cartoons are a form of rebellion or resistance, so I would like to inspire others who like my cartoons to show that, when we are in front of these authoritarians, we can mock, we can use humor as a weapon against this type of oppression.

Credit: Badiucao

Who are you trying to reach with your political cartoons? As you mentioned, most social media is blocked in China. Do you think you can get to the people you want to communicate with?

Yes, yes I do. Although the information in China is controlled so tightly, people manage to get around the Great Firewall to get access to Twitter or Facebook or Google and YouTube, so at the moment my main audience would be Twitter users from mainland China. According to Twitter’s own data it seems like there are tens of millions of Twitter users in China — I’m not 100 percent sure it’s that much — but they like to see the words and the views from different channels, not just from CCTV. Also, because I post my work on China Digital Times, for that group, they have a regular amount of subscribers who regularly see the works on there.

I see the people on Twitter as seeds to spread the message. Because, now, in China, the platform has transformed from Weibo to WeChat which is a social media platform that’s more intimate, more private. So sometimes I’ll have feedback on Twitter asking if they can spread my works on WeChat.

There are political cartoonists in mainland China. How important do you think visual elements are to dissent in the age of social media?

Yes, well, let’s start by talking about how the Great Firewall works — which censors the words. So if you’re putting any sensitive words in your sentence, it is much easier to be found and censored. They don’t even need to use any real person to find that word. If you are talking about visual language, it’s much harder to censor. I don’t think the AI is smart enough to say, “this is a political cartoon.” So in this way it plays a very important role in battling censorship, by spreading the word secretly. But also, compared with words, visual language is more direct […] Especially when something like a crisis or accident happens, visual language — whether it’s Photoshopped work, or a photo from the scene, or a cartoon — it circulates much faster than just words.

Credit: Badiucao

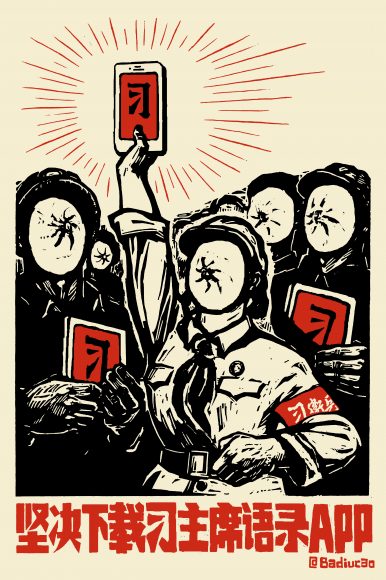

Well, let’s talk about your style: the deep reds and the scratchy blacks, somewhat reminiscent of a sort of rural, Soviet propaganda style. What were you trying to express with this distinctive style?

You’re actually pretty right on that. I feel like this style was picked up by the Communist Party’s propaganda machine, but originally it comes from German expressionism. They were left-wing artists as well but they started with wood-carving print work, which was introduced by Lu Xun in the beginning of the 20th century who brought this type of German expressionism back to China and played an important role as it became a mainstream art form. And then it got picked up by the government which added red instead of the black and white wood print. It got picked up the Chinese government and Soviet Union and finally it reached into the style that we know, the propaganda style […]

The reason I picked it is because, firstly, when we search to the German root, it is about expressing people’s pain in society, but once it was adopted by the communists, it changed. It was not a way to criticize. It was a way to prize. In my vision, I want to take it back to what it was, as if I’m using their own weapon against them. But also it reminds people of their history. People might argue that China is not the country it was — that they have open policies and introduced capitalism, and all that, but I would argue that it is still the same country being run by the same people. It looks different; if you only go to big cities like Shanghai or Beijing you will be amazed by the buildings and economic miracle, but the default of the state remains the same.

Credit: Badiucao

For our readers, you are currently wearing a mask. You keep your identity secret. Can you tell us why you think this is necessary?

I still think it’s very dangerous to express any political opinion on the Chinese government. Even though I’m in Australia, I can’t say I’m 100 percent safe. Let’s take the example the famous artist Ai Weiwei, who isn’t just an artist, who’s making work about current affairs in China, but the price is so severe: he got hit on the head, was disappeared for 81 days, and without them telling his family or his lawyers. Even for me, if my identity were leaked to the Communist Party, my family or friends back in China would get into trouble. All of this is based on real cases. Also, in Australia I don’t feel safe at the moment. With the Trump presidency, Australia is swinging between China and America day by day, and actually the whole nation is showing great favor with the bond with China. [Earlier] there was a show in Melbourne which was an opera from the Cultural Revolution. It was introduced in a major venue in Melbourne as a cultural exchange, but the nature of it is mainly Chinese propaganda. It’s a symbol that the so called soft power of China is invading different places — including Australia and America — every day.

As you mention, China has been picking up soft power in Australia for years, so do you think the choice Australia will have to make will have far-reaching impacts?

It seems the government is willing to get close to the Chinese government more and more, and at multiple levels. There was a controversy when one [member] of the Senate accepted money from China and it was just the tip of the iceberg […] Like this incident I experienced at a Confucius Institute in Adelaide, it was an artist from China who was giving her understanding of Chinese contemporary art. At the end there was a Q&A and I was asking about Ai Weiwei — cause back then his passport was taken away — and my question was not answered by the person who was invited. It was answered by a student. At the end, someone came to ask me for my ID and if I was a student, kind of like bullying me in a sense, telling me not to ask questions like that. This isn’t just my personal account. I guess there will be more samples and incidents like this in future. It’s become a major concern.

Before we finish, I would like to say something about Trump’s presidency and how it has influenced China. On Twitter these days, Chinese users are divided into two parts, one is pro-Trump, the others, like me, oppose him because he doesn’t care so much about human rights. It’s highly possible that he would make a deal with China (regardless of the human rights record in China) that would make things worse, but it’s worth talking to people about this issue because there are a lot of people who have the dissident perspective but are also pro-Trump. This is so absurd that those people see themselves as human rights defenders yet in the meantime support a politician who spreads hate and fear as Trump [does]. As to the majority people in China, the hate and fear toward Muslims created by the Chinese Government’s propaganda is strongly echoing with Trump’s policy. In China you can find a lot of hate and racist speech against this minority group day by day.

It feels like the whole world is crumbling and the belief in justice and the idea of universal human rights is shaking. Hence, as a personal statement, I want to stand with the Muslims and refugees from all around the world. That is because human rights are not something for trading but are universal rights for everyone in the world regardless differences in the religion, culture or skin color — regardless of whether the person might turn into a good person or a bad person, a useful person or a useless person.

Credit: Badiucao