Muazzama Qodirova, a Tajik lawyer, told RFE/RL this week that she is in Germany applying for political asylum. According to RFE/RL, she said “that Tajik authorities had threatened to launch a criminal investigation accusing her of leaking information about her client’s case to foreign media.”

Qodirova is the latest in an ever-lengthening list of lawyers hounded by Tajik authorities based on the clients they represent. In Qodirova’s case, she has been representing Buzurgmehr Yorov, the lawyer whose 23-year prison sentence — handed down in October 2016 after a closed trial — was recently extended by three years.

Yorov, and another lawyer specializing in human rights cases, Nuriddin Mahkamov, were arrested shortly after their most prominent clients: the leaders of the Islamic Renaissance Party (IRPT). The lawyers were accused and convicted of inciting ethnic enmity, calling for the overthrow of the government, support of extremist activity, fraud, and forgery.

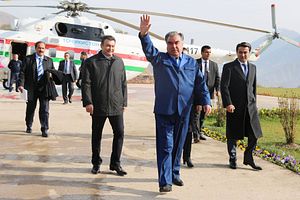

The IRPT’s downfall is a lesson in authoritarian consolidation. The party — arguably the heirs of the civil war opposition coalition — had settled into a comfortable spot as one of the very few legal opposition parties. They occupied two out of 63 seats in the Tajik parliament’s lower house and offered meek opposition to the government of Emomali Rahmon. It’s notable that the IRPT posed no real political threat to Rahmon, but they provided an outlet for expressing opposition to government policies.

Their “Islamist” title conjures (particularly in Western minds) beliefs about the party and its positions that don’t match reality. Perhaps the best demonstration of the party’s democratic credentials was their 2013 backing of a secular, female candidate for president (ultimately she wasn’t even allowed to run. Rahmon won against a handful of token alternates with 83.92 percent in an election that “lacked genuine choice” according to the OSCE).

Over the course of 2015 — a year I termed “Tajikistan’s Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Year” — the IRPT was squeezed out of government, erroneously linked to a mutinous general, and branded a terrorist organization. Its leaders were arrested, their lawyers were arrested, their families were harassed, and now their lawyer’s lawyer is on the run.

At present, the IRPT’s leader Muhiddin Kabiri is in exile, somewhere in Europe also seeking asylum. Dushanbe has managed to get Interpol to flag him with a Red Notice, demonstrating the authorities’ usage of international forums to pursue its enemies.

A year ago, in writing about a different lawyer whose children were being harassed and hounded by Tajik authorities, I asked, “Who will defend the defenders when all the lawyers are detained?”

And that’s exactly the point: Dushanbe wants no one to stand for the accused, whoever the accused may be. The absence of apparent opposition is easy to parlay into an image of broad approval of the government. In reality, however, the lack of visible opposition is a demonstration in the power of self-preservation and understandable wisdom of self-censorship in a country like Tajikistan.