For those in the West who have lived the second half of the 20th century, being under the United States’ tutelage was a mere fact of life. As the great victors of World War II and uncontested rulers of nearly every international institution in the world – UN, IMF, World Bank, GATT, NATO etc. – North Americans have transformed Central and South America into their own backyard.

Now change is said to be underway. Recent columns from the New York Times and the Guardian have drawn attention to the underlying risks of Trump’s grand strategy, that America’s newborn absenteeism issues an invitation for China to take over as the world’s paymaster. NBC News commentator Janis Frayer argued that, since Brazil, Argentina, Chile and Peru have become so economically reliant on China, so will the rest of Latin America fall for Beijing sooner or later. In The Diplomat, Antonio Hsiang went as far as to contend that the United States is making China great in Latin America, given Washington’s withdrawal from TPP (Trans-Pacific Partnership) and criticisms of NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement).

Which options are thus left on the table? What wild card can Latin American leaders possibly play in foreign policy in order to fight back on disdain and oblivion? It is tempting – and almost automatic – to point out the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as a potential shield for Latin America against Trumpism.

Is China Worth a Try?

As the current American president in office denies access to Latin American goods and people into the U.S.’ territory, while pushing the stigmatization of Latinos – who were verbally associated with “drug dealers” and “rapists” by Trump during his presidential campaign – and practicing massive deportation based on ethnic and racial criteria, should Latin American countries consider replacing Uncle Sam for Panda Bear as their ultimate political ally?

China shines as the fastest growing economy in the world during the last 30 years. Top position at gross domestic product rankings in terms of purchase power parity, bound for nominal leadership in U.S. dollars sooner than 2050, its figures related to demographics, military expenditure and politico-institutional apparatuses look astounding from the Global South. Almost every Latin American country today has China as a main commercial partner. Not to mention Chinese massive infrastructural investments all over the continent, with a clear emphasis on connectivity – seaports, airports, roads, bridges, telecommunication engineering and so on.

China’s physical presence is overwhelmingly felt these days – especially in big Latin American cities like Buenos Aires, Mexico City, and São Paulo, where the Chinese population already accounts for hundreds of thousands of individuals. Their diaspora is equally representative and visible in Manágua, La Paz, Lima, Havana and Santiago. Both symbolically and materially, Chinese people and private enterprises are already settled in.

If the above holds true, why does it still sound unnatural for many Latin American officials and citizens to seriously embrace the Beijing option? That is the one-billion-renminbi question.

Hearts and Minds

The reasons partly lie in soft power – or the lack thereof. There is no such a socially disseminated concept as “the Chinese way of life” in Tegucigalpa, Quito or Asunción. Despite heavily investing in cultural diplomacy – there are more than 450 Confucius Institutes around the globe now, in addition to hundreds of millions of U.S. dollars being spent on CCTV and Xinhua News Agency, two public media outlets run from Beijing – the country miserably fails in winning Latin America’s hearts and minds. Unlike South Korea and Japan, Chinese pop industry makes neither noise nor profit beyond national borders.

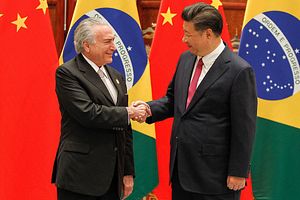

There is China’s diplomatic stance too. Beijing hardly considers Latin America a preferential target, be it for geopolitical or economic concerns. Being presented with a vast menu of strategic items, China can choose whether or not to involve in troublesome zones. Take the case of Brazil’s campaign for a United Nations Security Council (UNSC) permanent seat: Despite all the rhetoric on South-South cooperation and third-world solidarity, China has given no endorsement to Brasília’s candidacy. One can rest assured that, if an ecumenical and pragmatic path in foreign policy is to prevail, Chinese diplomats will not commit themselves to any particular position or single nation on Earth. Nor will it collide with the United States – one can predict on the grounds of the ‘peaceful emergence doctrine’ upheld by Xi Jinping.

Latin American diplomats, on the other hand, seem unprepared under many respects to engage in fierce negotiations with their Chinese counterparts and make the most of such encounters. If a bit of an exaggeration, American expert David Shambaugh claims that, while every Chinese ambassador posted to a Latin American capital city will most certainly speak fluent Spanish and/or Portuguese, barely a dozen Latin American career diplomats have adequate knowledge of Mandarin. Lisbon University researcher Débora Terra digs deeper and argues that there is still a huge gap between the parties – Latin America and China – when perceptions about one another are considered.

Since China is not a safe bet quite yet, and neither will the United States simply do for the time being, a quixotic dream of autonomy is what the region may be left with. Not so differently from, say, two centuries ago; back in the old days when Latin American peoples were gaining their independence from Spain and Portugal.

Dawisson Belém Lopes is a professor of international and comparative politics at the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG) and a researcher of the National Council of Technological and Scientific Development (CNPq) in Brazil.