In May 2017, India curtly and publicly declined to attend Chinese President Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Forum (BRF) in Beijing. India’s snub was both uncharacteristic and controversial, although not unexpected.

On May 13, 2017, a day before the BRF plenary, a spokesperson for the Indian Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) provided a formal explanation for India’s absence from the forum. From the statement it seems clear that there is a wide gap between the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) as it was understood by many participants at the BRF, and as interpreted by India’s MEA and much of India’s policy elite.

The terminology is certainly confusing: the ‘Belt’ refers to east–west land connectivity between the Pacific and the Atlantic via central Asia and Europe, while the ‘Road’ refers to the maritime arc that connects the land spokes. India’s deepest concerns seem to be with a particular spoke on the ‘Belt’ — the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor — and various points on the ‘Road’, notably Gwadar port in Pakistan, and the Hambantota and Colombo ports in Sri Lanka. There is no question that the BRI is diffuse, amorphous and Sino-centric in both conception and orientation. Yet the Belt component is already providing land connectivity to a large, resource-rich swath of central Asia, which is as much in India’s hinterland as that of Russia and Turkey — whose presidents both chose to attend the BRF.

Over successive governments, India’s foreign policy’s core objective has been to fashion an external environment that supports the nation’s economic and social transformation. Since India’s historic decision in 1991 to seek deeper integration with the world economy, this environment has included an open trade and financial order, whose rules were typically set by the richer countries — essentially the G7 — and acceded to by India. As articulated by President Xi in his speech at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland in January this year, China now presents itself as the flag-bearer for continued integration of the global economy at a time when support from richer countries, notably the US, is waning.

Frustration at the slow pace of reform of the established institutions of global governance — such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund — was an important motivation for China’s leadership in creating the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) which India was quick to join. It also drove Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa to jointly sponsor the New Development Bank headquarters in Shanghai, under an Indian chief executive. These are recent areas where India has found it helpful to support important Chinese economic initiatives.

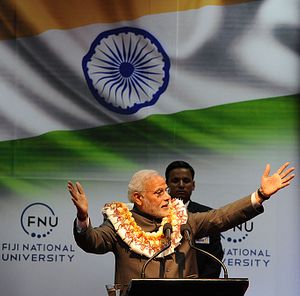

There is little doubt China’s BRI goals are much wider than just physical and digital connectivity, notably in its Asian hinterland. The arrival of China as an increasingly significant player in setting global standards may be uncomfortable for India, but is near-inevitable and needs to be planned for accordingly. In the weeks following the BRF, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his senior diplomatic officials have been engaged in a hectic circuit of visits and diplomacy, with a diverse set of partners and interlocutors. These have included the African Development Bank’s annual meetings in Gandhinagar (Gujarat, India); the meeting of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) in Astana, Kazakhstan where India and Pakistan were both welcomed as full members; a round of country visits to Russia, Spain, France and Germany; and most recently to the United States, Portugal and The Netherlands.

Particular note should be taken of Prime Minister Modi’s visits to a wide variety of European capitals in recent weeks. While he may have been lucky in his timing, the visits came soon after an unsatisfactory G7 summit in Italy and visible stress in the relationship between US President Donald Trump and German Chancellor Angela Merkel. The diplomatic visits also followed the election of French President Emmanuel Macron, which bodes well for a return to French–German leadership in Europe, at a time when the economy in the Eurozone is doing better than it has done in a while.

This is not to deny the significant differences that continue to exist between India, the EU and individual countries within Europe on a broad range of economic and social issues. It is rather to urge Indian policymakers to respond to the transformed global and regional environment in a couple of ways that may be novel for them.

The first is to engage more actively on issues of global and regional governance than India has typically done. With China’s rising prominence on the international stage, being a ‘free rider’ may be less agreeable for India than in it had been in a U.S.-led past.

The second, to import a phrase from European diplomacy, is to develop an instinct for ‘variable geometry’ — being comfortable with participating in shifting coalitions depending on the policy issue under discussion. Some of these could well include China, in others the interests of the two countries might differ. India’s diplomatic efforts have created goodwill with a broad spectrum of partners, notably the United States, Japan, France and Germany. As was demonstrated at the SCO summit, India has also maintained a working relationship with China, despite their many serious differences.

It will take fancy footwork to develop coalitions on economic issues of importance to India. But as India found in 1991, a time of global turbulence can also be a time of opportunity. The forthcoming G-20 summit in Hamburg provides a good opportunity to develop these skills.

Suman Bery is a Nonresident Fellow at the Economic Think Tank Bruegel, Brussels, and is a former Director-General of the National Council of Applied Economic Research, New Delhi. This piece originally appeared over at East Asia Forum here and is republished with kind permission.