The world is rapidly heading east. Evidence of this trend abounds in the west, especially in the realm of foreign policy-making. Former U.S. President Barack Obama inaugurated his mandate with an acknowledgment of Asia’s major role in the world. The “Pivot to Asia” doctrine, conceived to position Washington in favorable ways towards the recently noticed preeminence of China and India, not to mention the heightened importance of Japan, Indonesia and Russia. It would not take much longer for France, England and Germany to follow the same track and start investing heavily in bilateral and multilateral relations with eastern nations. Even a few peripheral states have managed to adapt their diplomatic strategies in order to better handle tomorrow’s international economics and politics – deeply influenced by the rise of Asia.

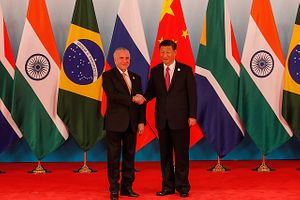

Confronted with this brave new not-so-western world, how has South America’s largest country been reacting? I am afraid not in the cleverest and most far-sighted manner. Having just flown back from China – where he attended the 9th BRICS Summit in Xiamen – Brazil’s current president Michel Temer is a laggard in this global race for gold. While neighboring Argentina and Chile have recently dispatched their heads of state to the Belt and Road Forum, a pompous high-level meeting convened by Chinese President Xi Jinping with the purpose of announcing Chinese infrastructural plans for the world to come, Brasília decided against sending a representative with ministerial credentials. That move – taken just a couple of months back – is meant to be illustrative on the scant degree of attention Beijing is getting from Brazil nowadays.

If one observer compares how diplomatic positions in Brazil’s embassies and consulates around the world are filled in, she will inevitably jump to this conclusion: Asia is being overlooked by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Whereas the Brazilian embassies based in Washington, London, Paris and Lisbon gather more than 20 career diplomats each (not to mention non-diplomatic staff), a glance at Asia’s main capitals – Beijing, Tokyo, New Delhi and Seoul – unveils a completely different scenario, since not even a dozen men and women have been posted to each Brazilian foreign mission.

Understaffed and unprepared, Brazil’s diplomatic corps also fail to catch up with their Asian counterparts at a most basic level: Although Chinese, South Korean or Japanese diplomats in Latin America will invariably be good speakers of Spanish or Portuguese, the opposite rarely holds true. The apparent lack of concern with Asia on the Brasília end has even triggered the sending of a letter to Brazil’s foreign minister in late July – signed by Brazilian ambassadors to China, Japan and India – when the experienced trio of diplomats attempted to raise awareness to this grave situation and wield pressure for a change of attitude.

Truth be told, though, that is a Brazilian foreign policy structural problem, whose origin predates and transcends Temer’s coming to office. Take, for instance, the “Science without Borders” university mobility program as a proxy indicator: Designed and implemented during the presidency of Dilma Rousseff, the program managed to send around 90,000 Brazilian undergraduate and graduate students abroad within five years. From this total amount, approximately 2,100 people chose a country like Hungary as an academic destination, while no more than 1,500 scholarships were destined to East Asia (including China, Japan and South Korea). That piece of information alone is telling enough on the failures of a governmental catching-up strategy which barely contemplates Asia’s cutting-edge schools – be they located in Beijing, Shanghai, Kyoto, Tokyo, Hong Kong, Taipei, Singapore, Kuala Lumpur or Seoul.

More than any other single aspect, foreign trade is Brazil’s Achilles’ heel when it comes to managing bilateral relations with Asian nations these days. Reasons for this very unsatisfactory diagnosis lie in the contents of commercial exchanges. In most of the cases, the South American giant basically buys manufactured goods and sells primary resources. Although huge balance-of-trade deficits might be prevented in the short run since East Asia, particularly China, has been demanding tons of soybeans, meat and ores from Brazil, these dynamics are clearly unsustainable in the long run and make Brazil easy prey in times of multiple accelerated turnarounds – usually driven by Asian hi-tech masters. At the end of the day, Brasília is believed to be entering a new “colonial” cycle that could prove even harder to escape.

Last but not least, there is the BRICS grouping. Once seen as the crown jewel, the Global South initiative has seemingly become an obsolete reminiscence of the days when Brazil could pose as an emerging power. To make the prospects a bit worse, if one looks into the figures related to intrabloc trade and cooperation writ large, she will quickly realize how ineffective this arrangement was in delivering a consistent surge in country-to-country flows. According to a report released not long ago by the Brazil’s secretariat for strategic affairs (SAE) – an agency attached to the president’s office – Brasília’s ‘BRICS Strategy’ has failed at every dimension, including the commercial one, as the exchanges remain very much asymmetrical and limited to Brazil-China bilateral flows. As a commentator from India recently put it, considered the unenthusiastic way the Planalto has been dealing with the Global South league, an exit strategy on the part of Brazil – the so-called ‘Braxit’ – would not be an unthinkable policy choice for the future.

All taken into account, Brazil is under heavy pressure. While the country’s officials still look uncomfortable and even perplexed with the rise of Asia at the global chessboard, they know they need to respond accordingly to the ‘easternization’ conundrum. If they don’t, much would be at stake.