Why did the United States decide to seize the Philippines while waging a war against Spain over the fate of Cuba? Support for the seizure of the Philippines within the United States was less strong than is commonly assumed. Accounts of the U.S. decision to seize the Philippines often treat it as an extension of Manifest Destiny, the idea that the United States had a unique civilizing mission on the North American continent and beyond.

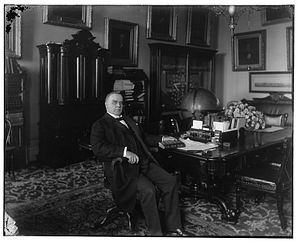

A recent article by Philip Zelikow in the new Texas National Security Review (associated with the website War on the Rocks) investigates this question through a deep dive into the deliberations of the McKinley administration. The short answer is that McKinley did not have much in the way of a well-thought out plan for seizing the Philippines, but instead did so largely out of operational dynamics associated with the presence of the U.S. Navy’s Asiatic Squadron in the region. Then, bolstered by war rhetoric, imperial advocates won the intra-administration battle for annexation, an outcome few had envisioned at the beginning of the war.

The problem began with the U.S. Asiatic Squadron, a task force based out of British Hong Kong intended for anti-piracy work. Extant understandings of neutrality meant that the Asiatic Squadron could not remain in Hong Kong, or take advantage of any other neutral ports in the region, after the beginning of hostilities with Spain. In effect, the United States needed to use the Asiatic Squadron or lose it. And the best way to use it was in an attack on Manilla.

The U.S. Navy won a quick victory at Manilla, which led to follow-on operations to seize much of Luzon. Philippine rebels asserted control in much of the rest of the archipelago, initially welcoming U.S. intervention. Many within the administration viewed the seizure as strategic; the archipelago could be used to extract concessions from Spain during peace negotiations.

However, the McKinley administration had set a rhetorical trap for itself. After concentrating its public war rhetoric on (truthful accounts of) Spanish depredations in Cuba, the administration found it difficult to make a case for returning the Philippines (unwillingly) to Spanish control. Having made a fundamentally moralistic argument in favor of war, the McKinley administration found itself trapped in its own crusade.

But what of simply freeing the archipelago? Rebel groups in the Philippines were already assembling military and governmental institutions, and expected independence on terms similar to Cuba. U.S. commanders on the spot, however, felt that these institution would quickly collapse under foreign intervention. Both Germany and Japan had imperial ambitions, and either might have preyed upon either an independent Philippines, or on the decaying corpse of the Spanish Empire. Indeed, the Germans quickly deployed naval vessels to the region as the outlook on the future of the Philippines grew cloudy.

The international situation forced McKinley to reconsider his initial position, which was a quick return of the bulk of the archipelago to Spanish control. The advocacy of imperialists within his cabinet, along with an overly optimistic set of assessments regarding the military difficulties of maintaining control, led the president to shift his position towards formal, if temporary, control.

Victory at Manila then, in effect, set the United States on a path that led to the seizure and control of the Philippines. In the end, the United States committed itself to fighting a guerrilla war against its erstwhile allies, and occupying the Philippines into the 1940s. The bureaucratic and rhetorical trap that the McKinley administration created for itself would prefigure similar experiences by later administrations; over the top rhetoric, proxies with irreconcilable interests, and opportunistic foreign players eager to take advantage of instability.