Much has been written about the inability of Central Asia’s two poorest states – Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan – to pay back their loans to China. Beijing holds 41 percent and 53 percent of Kyrgyzstan’s and Tajikistan’s external government debt, respectively. Certainly, there are risks but so far both countries are actually managing their debt quite well. Chinese loans are highly concessional. The current debt loads and repayment schedules for both states are manageable.

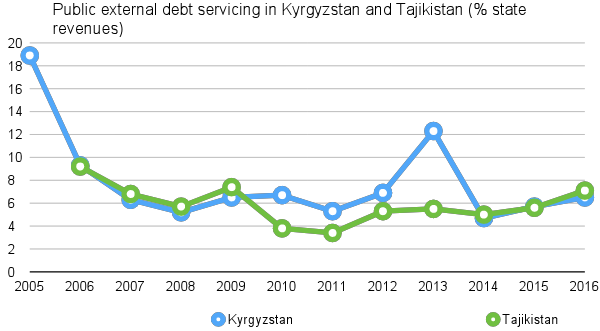

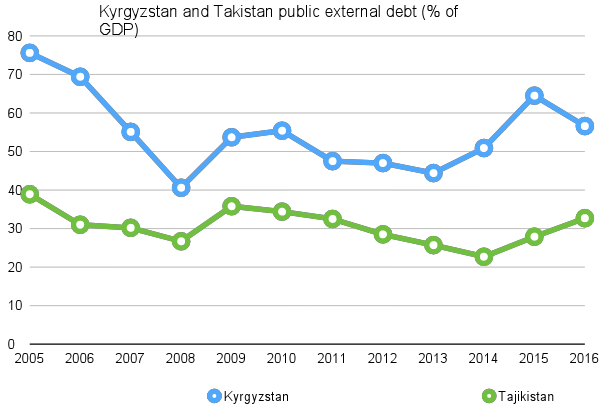

China started lending large sums of money to Tajikistan in 2006 and Kyrgyzstan in 2010. Since then, Tajikistan’s and Kyrgyzstan’s debt positions have barely changed. Both countries‘ debt to GDP ratios are about the same as when China started seriously lending to them. Debt servicing (as a percentage of budgetary revenues) has been maintained at a manageable 5 to 8 percent in both countries. This has been achieved through strong economic growth, normal repayment of debt and the cancellation of earlier Russian credits.

There will be an incremental increase in repayments on current loans for both Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. Chinese loans are almost all offered at 2 percent interest, repaid over 20 years with a grace period of varying lengths. As the grace period ends for these loans, repayments will increase.

Source: National Bank of Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan Ministry of Finance and IMF

Source: National Bank of Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan Ministry of Finance and IMF

The Kyrgyz and Tajik governments have made a very simple bet: Economic growth rates in will outpace the growth in debt repayments. Kyrgyz Minister of Finance Adylbek Kasymaliev, speaking in December 2016, said:

The peak of repayments will not be in 2018, but for the period 2024-2031. Then each year loan servicing will go from $250 million to over $300 million [$308 million in 2024 to $338 million in 2028]. But I would like to quote other figures. In 2010, budget revenues amounted to 49 billion Soms, and in the current year already amount to 124 billion Soms [$1.79 billion, rate at December 22, 2016]. So, in six years, revenue has grown threefold [actually 2.5 times]. Accordingly, by 2024, GDP and revenues will also increase. I think by then the income will allow for paying out the loans.

Kyrgyz government debt repayments in 2016 were $144 million. This will jump to $200 million in 2018 and $308 million in 2024. To maintain debt servicing at 2016 levels, budgetary revenues would need to grow 2.1 times by 2024, which is a slower growth rate than occurred between 2010 and 2016. In the first nine months of 2017, Kyrgyz government revenues grew by 11 percent.

Repayment requirements will increase more slowly in Tajikistan than Kyrgyzstan. Over half of China’s debt to Tajikistan was disbursed between 2007 and 2010. The grace periods for these loans are finished and Tajikistan has been repaying the principal successfully for a number of years. Also, Tajikistan’s total external government debt (Chinese or otherwise) changed very little between 2011 and 2016.

With a slow recovery underway in Russia, the World Bank is predicting GDP growth rates of about 4 to 6 percent for Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan in the next few years. But, even if government revenues do not grow at the same rate as debt servicing, there is still room in the Tajik and Kyrgyz budgets to allocate a higher proportion of government funds to repayments.

So, the current repayment schedule is manageable, but if either country takes on excessive new debt or there are external shocks, their budgets could come under pressure fairly quickly.

And new debt sources are on the horizon. Both Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan are running sizable budget deficits that mean, in the short term, new debt acquisition is unavoidable.

It is also possible that the countries will take on large new loans for infrastructure projects. Both countries are trying to walk a fine line between fiscal responsibility and desperately needed public investment. It is always possible that they tip the needle too far toward the latter.

One such concern is Tajikistan’s recent issue of $500 million in bonds. This is new government debt issued at 7.125 percent. The Tajik government plans to use this for the Rogun dam, a project that both China and multilateral donors have avoided. The bonds threaten to stretch Tajik repayment capacity more quickly than Chinese loans at 2 percent. The bonds proved incredibly popular with international investors in search of high yield, so Tajik authorities might issue more. They could catch on in Kyrgyzstan, too.

Finally, there is the risk of external shocks. Most Chinese loans are denominated in U.S. dollars. A sizable depreciation in local currencies would put budgets under pressure. Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan lack the foreign currency reserves to manage currency fluctuations. Both countries’ relative lack of exports also deprives them of another potential source of foreign currency to buffer against external shocks.

So, there certainly are risks. Currency shocks and high interest bonds in Tajikistan are of particular concern. But when it comes to managing highly concessional Chinese loans, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan actually have pretty good records.

Dirk van der Kley is a Research Fellow at Narxoz University and a PhD Candidate at the Australian National University.