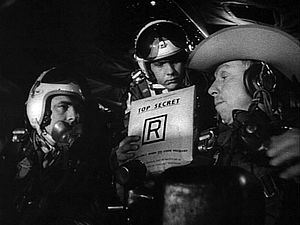

Fifty-four years ago in January, Stanley Kubrick’s dark comedy about accidental nuclear war, Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, premiered at movie theaters across the United States. The movie immediately attracted controversy as it suggested that a mentally unstable U.S. Air Force commander could order a nuclear attack on Soviet Russia without consulting his superiors, including the U.S. president.

Dr. Strangelove trailer (1963)

Various defense intellectuals and government officials dismissed the film as “impossible on a dozen counts”– especially the movie’s essential plot device of presidential pre-delegation of nuclear weapons use which, as one former Pentagon official said, could not be “further from the truth.” However, we now know that top U.S. military commanders indeed had presidentially authorized instructions providing them with the authority to launch nuclear weapons.

As declassified U.S. documents show, such pre-delegation existed beginning in 1956 when then U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower authorized U.S. air defenses to use nuclear weapons to defend against Soviet bomber forces in the event of an attack. This was further solidified with Eisenhower approving pre-delegation instructions for the use of nuclear weapons in 1959. Some form of nuclear pre-delegation existed at least until the end of the 1980s, as Bruce G. Blair has shown.

Daniel Ellsberg, a high-level nuclear war planner in the 1960s, notes in The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear War Planner that during the Cold War years, pre-delegation was seen as an integral part in the nuclear arms race with the Soviets for a simple reason: Its absence would undermine nuclear deterrence. Ellsberg writes: “The theatrical device represented by the president’s moment-by-moment day-and-night access to the ‘football’, with its supposedly unique authorization codes, has always been that: theater — essentially a hoax.”

He continues: “Whatever the public declarations to the contrary, there has to be delegation of authority and capability to launch retaliatory strikes, not only to officials outside the Oval Office but outside Washington too, or there would be no real basis for nuclear deterrence.” Or to put it more succinctly: Without pre-delegation, nuclear deterrence would be no more than an empty bluff, according to Ellsberg. This seems to have been generally accepted wisdom in the Pentagon at the time.

For example, Strategic Air Command (SAC), responsible for command-and-control of U.S. strategic bombers and intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) purportedly had pre-delegated authority to execute the so-called Single Integrated Operational Plan (SIOP), the United States’ general plan for nuclear war. Throughout the Cold War years, SAC also maintained an airborne command post with a one-star Air Force officer who had the delegated authority to execute nuclear war plans.

The first SIOP of the late 1950s to early ’60s, based on the massive retaliation doctrine, was a first strike plan targeting every city of 25,000 or more in China and the Soviet Union, next to military targets, with thermonuclear weapons with five to 25 megatons in yield. The Pentagon estimated that such an attack would kill 275 million in the first few hours and another 325 million in six months. Another 100 million would die in Eastern Europe, next to 100 million deaths of Western Europeans.

These estimates were calculated before the discovery of nuclear winter (the idea of nuclear winter remains contested) and also left out fatalities by firestorms caused by thermonuclear weapons. It also did not include the effects of Soviet retaliatory strikes. If the first SIOP would have been executed, it likely would have killed nearly every human being on the planet, the majority by a global famine as a result of reduced sunlight and lower temperatures. In more than one sense, the first SIOP was the real-world equivalent to Kubrick’s fictional Doomsday device in Dr. Strangelove and it could be launched by dozens of U.S. military officers.

Furthermore, throughout the 1960s, most nuclear weapons did not have coded switches, so-called permissive action links (PALs), to prevent the unauthorized use of nuclear weapons. These safeguards, essentially electronic locks, were later installed on ICBMs so that they could not be fired without a valid code sent from higher headquarters. However, according to Bruce G. Blair, a former Minuteman ICBM launch officer, the launch codes were continuously set at 00000000. This purportedly was true into the early 1970s (but continues to be denied by the U.S. Air Force).

Blair notes that he was specifically instructed to double-check the locking panel to check that no digit other than zero had inadvertently been dialed into the panel. “SAC remained far less concerned about unauthorized launches than about the potential of these safeguards to interfere with the implementation of wartime launch orders,” Blair states. “And so the ‘secret unlock code’ during the height of the nuclear crises of the Cold War remained constant at 00000000.”

As Ellsberg emphasizes: “Effective safety catches, whether in the form of rules of physical safe-guards, meant potential delays in response. And delays were anathema, dangerous to the mission—of disarming the enemy—and to the survival of the weapons, the command system, and the nation.” He also writes that the lack of proper safeguards to prevent the unauthorized launch was also partially the deliberate result of distrust by U.S. military officers of the judgment of civilian commanders in a crisis.

Consequently, the lack of safety mechanisms on ICBMs such as PALs that would prevent their unauthorized launch was partially connected to the military’s idea that under certain circumstances, military officers have to take matters into their own hands when it comes to national survival in a thermonuclear war — not far removed from Kubrick’s mad U.S. Air Force general, Jack D. Ripper. At the end, it was deemed more important by nuclear war planners to launch nuclear weapons before they are destroyed on the ground than to prevent false alarm or unauthorized action.

(Today, security measures used to prevent the unauthorized or accidental launch of nuclear weapons purportedly are vastly superior to those in the early 1960s.)

Dr. Strangelove, Ellsberg notes in his book, also correctly portrayed the inability for the U.S. president or senior military commanders to recall strategic bombers and order them not drop their thermonuclear bombs on a pre-designated target once they went beyond their positive control line. (ICBMs cannot be recalled in any way.) This was despite the fact that some U.S. bombers would have needed as much as 12 hours to reach their targets, during which the military and political situation could have changed dramatically. Indeed, bomber crews were specifically instructed to disregard unauthenticated orders to stand down.

According to Ellsberg, one of the reasons given to him for this was that “‘the Soviets might discover the Stop code and misdirect the whole force back.’ This is precisely the explanation given to the president in Dr. Strangelove for his lack of ability to send a Stop order to the planes that were fraudulently launched. I was dumbstruck by this point, among others, when I first saw the movie in 1964.” The accurate portrayal of U.S. nuclear war operating procedures in the film was the product of the screenwriter Peter George, who was a former Royal Air Force Bomber Command flight officer with intimate knowledge of Bomber Command control systems, which apparently were similar to those of SAC.

Bruce G. Blair, however, recently told The Diplomat in an interview that termination Sealed Authenticator System (SAS) codes did exist for much of the sixties and beyond and that it was possible to recall strategic bombers after they passed their positive control line. “I used to check them just like the execution cards during crew changeover to guard against tampering,” Blair said. He adds that Ellsberg may have been right with his assertion that bombers could not be recalled during the late 1950s.

The answer to the question “How many fingers are on the nuclear button?” was one of the most closely kept secrets in the United States throughout the Cold War years and it continues to be clouded in mystery to this day. Officially, no presidential pre-delegation of nuclear weapons use is in place. Yet that does not mean that it does not exist. “Currently, it is not publicly known whether any pre-delegation of authority to launch nuclear weapons continues to exist and, if so, under what constraints,” according to an October 2017 analysis by the Carnegie Endowment for international Peace.

“Every president from Eisenhower through Reagan pre-delegated launch authority to a raft of generals and admirals to hedge against the decapitation of Washington,” Bruce G. Blair, who recently published an analysis on options for reforming presidential nuclear launch authority with the Arms Control Association, told The Diplomat.

“Even if a presidential successor survived, it was very likely that the military commanders would have authorized a large-scale strike before the successor could take command. After the Cold War ended, this pre-delegated authority was rolled back and it remained so through the Obama administration [I have five highly credible inside sources for this statement]. The situation under Trump is unknown to me.”

Even if some form of pre-delegation does exist, it would be highly classified. “Pre-delegation is less of an issue than it has been in long time,” Hans Kristensen of the Federation of American Scientists said on Twitter recently. “Strategy trend is to place less emphasis on launch under attack and more on riding out attack. Except perhaps in cyber scenarios. But there’s so much smoke about what’s real vs. fantasy.” As it turned out in the 1960s, however, the purported command-and-control fantasies of Dr. Strangelove were closer to reality than even most government officials would have known at the time.