There are numerous examples of the successful and tangible manifestations of China’s Africa policy all across the continent. Two recent projects have placed a spotlight on Ethiopia, where the Chinese presence is overwhelming: the first modern light railway (tram) system of sub-Saharan Africa in the capital, Addis Ababa, and the Addis–Djibouti railway, connecting the landlocked country to the maritime trade routes of the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea. In this two-part analysis, we evaluate these Chinese investments after visiting these projects in January 2018. Below, we examine the light railway in Addis Ababa; in Part 2 we look at the Ethiopia-Djibouti rail connection.

The light railway system in Addis Ababa provides unusual scenery, a unique example of mass public transport in sub-Saharan Africa. The image of elevated tracks implies a vivid, developing, and growing country, and it is easy to see why Ethiopia’s decision makers wanted to build it. But behind the curtain, the elevated tracks have not made life better for many Ethiopians.

Construction on the light railway started in December 2011 after securing funds from China’s Export-Import Bank (Exim Bank). The final cost of the railway was $475 million, 85 percent of which was covered by a substantial concessional loan from Exim Bank. It took three years for the China Railway Group Limited (or CREC, the acronym of the parent company China Railway Engineering Corporation) to finish the two-line, 34.4-kilometer system. Trial operations started in February 2015, while the lines started to operate by September 20 and November 9, 2015.

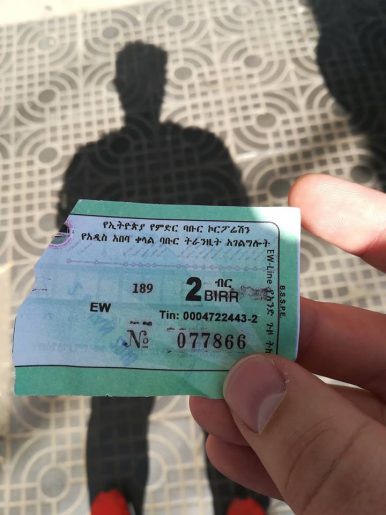

A 2 birr ticket for the light railway. Photo by Zoltán Vörös.

According to the official figures, the system carried on average 105,000-110,000 daily passengers in the first 14 months. Tickets currently cost two to six birr ($0.08 to $0.20) depending on the distance of the trip. Tickets are easy to buy at orange colored kiosks next to each station.

The initial plan was to ease the traffic in the capital, but according to critical voices, the light railway failed to achieve this goal. Logging around 110,000 daily passengers in a city with 6-7 million inhabitants (no official and correct figures are available) shows the light rail has a very limited relevance.

With these ticket prices, the train is comparable to the cost of a bus ride, but the light rail is way overcrowded and the network reaches only certain parts of the city. The number of trams should be increased, but according to the news as well as locals, the system is limited because of power issues. Even with the current number of trams, it runs infrequently or with single cars. There have been reports about a dedicated power grid, but even if it is there, it fails to fully operate the system.

Instead of easing traffic, locals actually blame the light railway for making things worse. The tracks are elevated at some parts and cut between and through road lanes at other parts of the city, making it harder to cross to the other side for cars and minibuses. It is also not easy for pedestrians to cross the road to reach stations where there is no overhead crossing; it can be literally life threatening, as we experienced it. In some cases, we had the feeling that the builders failed to plan the attached infrastructure properly.

Elias Kassa, a professor of railway science at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, confirmed this view; he commented on the project, saying that planners had failed to integrate the new light rail with the pre-existing bus system. There were also comments about the fact that the rail project was not even part of the Addis Ababa Master Plan.

At this point, we need to make mention of the Chinese involvement. Financed by a Chinese loan, constructed by a Chinese company, and operated with China-made trams, the light rail project is truly a sign of enhanced China-Africa cooperation. There were rumors about European loans as well, being offered to help ease the traffic of Addis Ababa, but not specifically for the light rail system. However, Ethiopia turned toward China since they would make it easy to realize the project, which highlighted Ethiopia’s prestige. And while in this sense the project was successful, and has caught the attention of other cities (there are rumors about similar projects in Lagos, Nairobi, and Lusaka), the traffic issues are still unresolved.

It is not just the traffic Ethiopia has to worry about, however. Soon they have to start paying back the Chinese loan, and the project is barely making a profit. The owner, the Ethiopian Railway Corporation, said that the light rail has a daily income of around 400,000 birr ($14,000) but there are issues with those who board the train without purchasing a ticket. Meanwhile, it is unclear who receives this money. The system is operated by a Chinese company, Shenzhen Metro Group. They received the rights in December 2014 with a contract worth $100 million for three years (starting in the first quarter of 2015 and terminating in August 2018; the contact includes provisions about training local personnel in order to be able to take over operations after August 2018.). According to the news, the contract includes the operation and maintenance of the lines as well. All this means that the Chinese company is likely to receive the income from ticket purchases.

A view of Addis Ababa’s light rail. Photo by Istvan Tarrosy.

Undoubtedly, China has built much-needed transport infrastructure that can increase Africa’s connectivity with the rest of the world, which in turn can contribute to a higher level of integration into the world economy. Chinese construction companies not only produced new ports, extended and modernized airports, and major railroads, but also new tarmac roads linking major regional hubs, including the various townships with proper connection to large cities. As Xiaochen Su underscored in a piece in The Diplomat, however, “African states are likely to require more than just portions of their limited budgets to complete repayment.” We may not agree with Su’s view on “a brand-new type of neocolonialism,” but we can also point out African vulnerability, which – in the case of Chinese infrastructure loans – surely escalates African dependence on China.

Public transport will never be profitable in the way discussed, yet somehow Ethiopia has to start slowly repaying its loans. As we will discuss in part two, with a look at the other benchmark transportation project of China in Ethiopia, the struggle to receive decent incomes from such projects is not an isolated case.

Dr. Istvan Tarrosy, Ph.D. is Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Pecs, Hungary. He is Director of the Africa Research Centre and Secretary of the Africa Sub-Committee of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

Dr. Zoltán Vörös, Ph.D. is Assistant Professor at the University of Pecs, Department of Political Science and International Studies.