At last month’s national conference on cybersecurity and informatization, China’s President Xi Jinping delivered another speech on building China into a national power in cyberspace. This is the third speech on the same theme given by Xi at a series of top-level national cybersecurity meetings since 2014. Defining and protecting China’s critical information infrastructure (CII) is one of the recurring issues mentioned at all three events.

In his 2016 speech on cyber strategy, Xi highlighted that the priority sectors requiring CII protection are finance, energy, telecommunications, and transportation. He also called on the government to deepen research on CII protection and accelerate work on building a national CII security assurance system. In the most recent comments, Xi took a more nationalistic and authoritarian tone, closely tying CII protection to domestic cyber industry capacity building and consolidation and centralization of cybersecurity information collection platforms. He also urged regulatory authorities to supervise the implementation of CII protection policies and CII operators to take full responsibility for critical infrastructure cybersecurity assurance.

Xi’s not-so-subtle signal pushing for the implementation of CII protection policies will likely be a wakeup call to the slow moving bureaucratic effort of formulating China’s CII Protection Regulation (Regulation). The first draft of the Regulation was published for public comment in July 2017 and was originally scheduled to be finalized by June 1, 2018. However, key drafters of the Regulation have been struggling to agree on the final text due to differing views regarding the scope of CII and competing sectoral authorities’ varying approaches toward CII cybersecurity assurance. It is unclear whether the drafters will finalize the Regulation according to the planned timeline. It’s even more uncertain if outside stakeholders will have an opportunity to provide feedback before its completion. Against this backdrop, it seems Xi is taking note of the lack of progress in developing CII policies and pressing for implementation in an area where a key piece of regulation has not been published.

In fact, China has been attempting to grasp the issue of CII protection for over 10 years. As early as 2007, China’s Ministry of Public Security (MPS) issued the Administrative Measures for Information Security Multi-Level Protection Scheme (MLPS). The MLPS classified all information systems into five levels according to the system’s potential negative impact on national security, social order, and personal interests if information security breaches occur, with level 5 being the most critical. Viewed as China’s first infrastructure protection policy framework, the MLPS mandates that systems rated level 3 and above adopt only products with Chinese intellectual property (IP). Its static, consequence-based approach was modeled on the now abandoned U.S. Department of Defense’s trusted computer system evaluation criteria, or the “Orange Book,” from the 1980s.

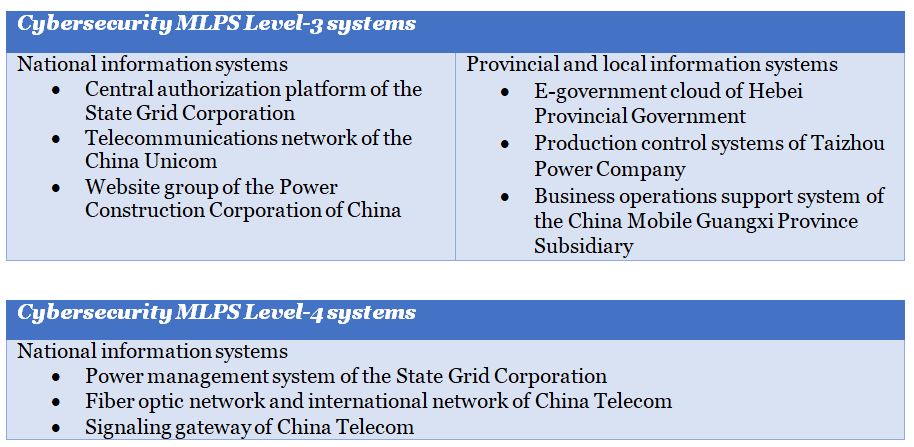

As the concept of information security evolved to become cybersecurity, and a risk-based approach gained popularity in the global cyber community, the MPS vowed to upgrade MLPS to incorporate more dynamic cybersecurity safeguard elements for the protection of modern CII. In a January 2018 speech, the lead drafter of the latest version of the Cybersecurity-focused MLPS, Guo Qiquan of the MPS, provided several examples of cybersecurity MLPS level 3 and level 4 systems, falling under the scope of CII, without disclosing the methodology used to designate CII or any additional developments regarding the draft upgraded MLPS. His CII examples include the following systems:

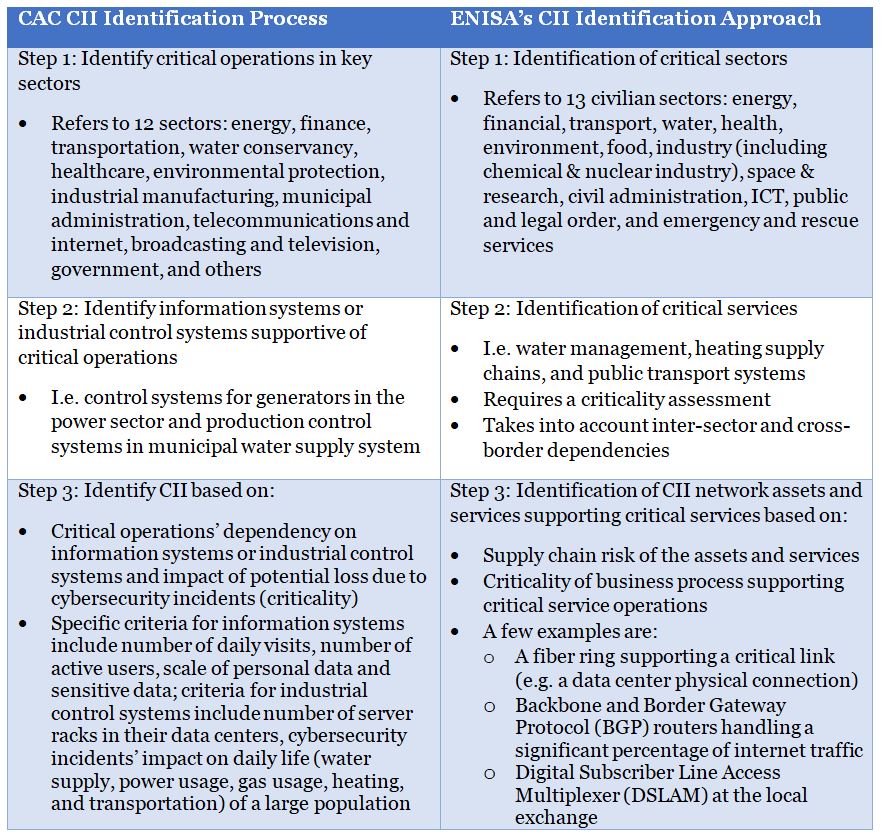

On the other hand, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) has been leading the development of the Regulation, including the identification criteria of CII cross sectors. According to the June 2016 National Cybersecurity Inspection Operational Guide issued by the Cybersecurity Coordination Bureau of CAC, CII identification shall follow a three-step process. This methodology of CII identification seems to mirror key elements of recommendations from the 2014 European Union Agency for Network and Information Security (ENISA)’s Methodologies for the Identification of Critical Information Infrastructure Assets and Services. This ENISA study also suggests a three-step approach to identify CII assets. Below is a comparison of the CAC process and the ENISA approach.

A major difference between the two methodologies is that the ENISA recommends assessing criticality and dependency of critical services before identifying CII assets and services while the CAC process emphasizes the criticality and dependency of specific CII systems and differentiates the supportive roles of information systems and industrial control systems to critical operations.

Another noticeable divergence between the two methodologies is that the ENISA study highlighted that for Step 2, the identification of critical services can be done by a state-led, top-down approach, or a critical services operator-driven, bottom-up approach. The top-down approach is more systematic and strict, while the bottom-up approach is more pragmatic, as the significant complexity of CII is best understood by the operators themselves. China clearly took the top-down approach to CII scoping and is likely facing the challenge of understanding the technically sophisticated criticalities and dependencies of CII components.

Xi Jinping mentioned in his latest speech that CII operators should “take full responsibility for critical infrastructure cybersecurity assurance.” This comment seems to highlight the current CII policy challenge for the working-level bureaucrats, specifically that operators have yet to take full responsibility for CII protection. From the CII operators’ perspective, they would like to see additional responsibilities to be paired with additional rewards.

To address the challenge of insufficient CII stakeholder participation, the CAC and the MPS need to provide incentives for operators and their supply chain partners, offer cybersecurity technical support, and help improve the regulators’ understanding of CII operation. To take the first step toward constructive public-private sector collaboration, the CAC may consider providing a meaningful consultation process for the Regulation’s latest draft and the MPS might engage technically savvy stakeholders in the early stage of the upgraded MLPS development.

Xiaomeng Lu is Access Partnership’s International Public Policy Manager and China practice lead