A herbalist in a small ethnic village in the mountains of southwest China who became a much-visited tourist attraction has died, a few years short of his 100th birthday.

Known as “Dr. Ho,” English-speaking He Shixiu rose to prominence after being profiled in a New York Times article by travel writer Bruce Chatwin in 1986, and later featured in Michael Palin’s BBC television series “Himalaya.”

Over the last three decades, He was listed as an attraction in travel guidebooks, including the popular Lonely Planet. Since being thrust into the limelight in the late-1980s, the self-taught doctor received over 100,000 patients and guests, mainly visitors from abroad, including celebrities, dignitaries, royalty, and journalists. As his fame spread, the renowned physician became the subject of over a thousand articles in more than 50 languages, making him the most-written-about Chinese doctor in the world.

Nakhi-minority He Shixiu initially taught himself traditional Chinese medicine and studied Western medical textbooks in order to recover from tuberculosis contracted in 1949 while serving with the People’s Liberation Army, shortly after graduating. Having cured himself, he continued his study of the healing properties of plants found only in the Tibetan borderlands of Yunnan province, along with traditional Nakhi knowledge of herbs. From his home in Baisha, located at 2,500 meters (8,200 feet) above sea level, he started to treat people’s ailments.

His university education and family background led to him being labelled a “counter-revolutionary” and “imperialist running dog” in the late 1950s. Sent to harsh countryside “re-education” camps, he continued his research while hiding in the hills. During the Cultural Revolution, he buried his medical and botanical books under the floorboards to avoid having them seized and burnt by the rampaging Red Guards. “We were very, very poor,” He said of this time. “We had nothing.” He lost most of his teeth.

Having been barred from practicing for decades, it was only following the 1978 Open Door Policy of Deng Xiaoping that the “rehabilitated” doctor was finally granted a license to practice. He was already in his 60s. In 1985 he set up the Jade Dragon Snow Mountain Herbal Clinic in his traditional-style red-painted wood and mud-brick house.

China’s opening up and the lifting of foreign travel restrictions and permits for “foreign aliens” in the mid-1980s saw intrepid travelers make it inland and up to the cobblestone and canal town of Lijiang, and to Dr Ho’s village, famous for its temple frescoes, traditional crafts, and the rare English-speaker such as Dr Ho.

He Shixiu had learnt from missionary teachers in Lijiang and U.S. Flying Tiger signalmen based at Baisha during World War II, and he worked as a tutor at the university’s foreign languages department in Nanjing after originally studying engineering at the Shanghai Naval Mechanical College. But his main English teacher was the last foreigner to live in Lijiang before the Communists took over in 1949. Dr. Ho’s father had been a translator for National Geographic explorer Joseph Rock, who lived in the next village for more than three decades.

After the turbulent times, He taught English at schools and colleges in Lijiang, before being able to work in public hospitals and then open his own clinic.

Writer Bruce Chatwin’s quest to find Joseph Rock’s legacy took him in 1985 to Baisha, which (like Lijiang and the Nakhi minority) was virtually unknown to the outside world. During the two weeks he spent in the area, he attended a christening banquet for Dr. Ho’s grandson and wrote up the encounter for the New York Times as “In China, Rock’s Kingdom,” published in 1986.

With more stories about the outgoing doctor, his herbal cures, including documented cases from a Mayo Clinic leukemia patient and a prostate cancer survivor, and the elderly man’s gregarious personality, an increasing number of travelers from around the world sought out the medicine man. Sometimes the outgoing doctor would stop visitors in the main street of Baisha and introduce himself, saying, “Hello. Are you looking for me? I am the famous Doctor Ho.”

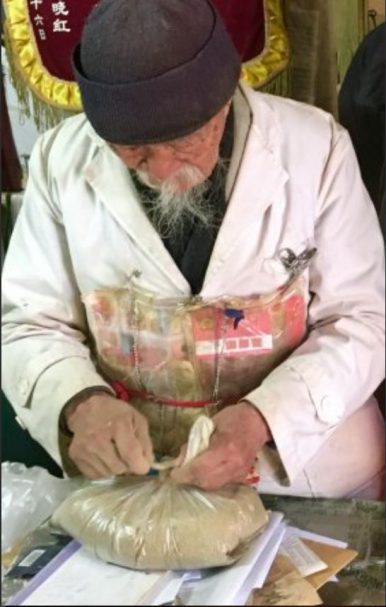

With his trademark doctor’s medical gown, knitted hat, and white wispy goatee, the diminutive but sprightly doctor would invite passersby into his spartan clinic, which was advertised with a sign and placards of laminated newspaper cuttings. “Come in. Nice to meet you,” was He’s typical welcome. “You must have heard of me. I’m in every guidebook.”

His dimly lit waiting room, which had a musty herbaceous smell from the containers of powdered herbs, was lined with framed newspaper articles, handwritten letters of thanks, testimonials by medical professionals, thousands of collected business cards, numerous awards, and black and white photographs.

Visitors would be seated on wooden benches and Dr. Ho’s assistant or his wife Min Chaoxin would serve the doctor’s secret “Happy Tea,” with his son He Shulong, also a herbalist, sometimes explaining about the unique healing plants found in the region, and his father’s rise to fame.

He treated all comers, without the need for appointments, and donations were only sought to cover the costs of the herbal formulas and to enable him to treat others who couldn’t afford it. Each week the clinic would receive requests for more medicine from former patients, and the clinic sent powdered herbs around the world.

Southwest China expert Michael Woodhead, writer of “In the footsteps of Joseph Rock,” first met Dr. Ho in the early 1990s, when the doctor was already one of the region’s personalities on the tourism radar. “He was one of a few colorful local personalities who spoke English and welcomed Western tourists, who were otherwise bewildered by a very foreign China,” Woodhead remembered. “Certainly he was a bit eccentric and obsessive, but he was unfailingly enthusiastic and hospitable, a sincere man who genuinely welcomed people into his home to talk about his passion, traditional herbal remedies. His English was mangled but uninhibited, and you could spend an afternoon with him expounding his theories of ‘wellness’ – this was two decades before Gwyneth Paltrow.”

Woodhead says Dr. Ho is a legend. “Yes, he was a shameless self-publicist, but he was not a fake. He was the real deal. And he really believed in the herbs.”

Despite the attention and fame, and the doctor’s frequent reference to his many accolades, Dr. Ho once said the reason so many visitors from abroad came to his clinic was for the herbal cures: “It is not about how great I am, but about how great the herbs and traditional Chinese medicine are.” He saw his work as a continuation of his father’s.

However, Dr. Ho did thrive on the publicity. The frequent visits by travelers meant he would give his spiel in stilted English, show a typed out transcript of his philosophy, give the appropriate guestbook to sign depending on nationality, and have a photograph with the visitors outside the clinic entrance. He often posed for photos, a twinkle in his bright eyes, his hands on the grubby lapels of his lab coat, which became decorated with badges and commemorative pins. He would then repeat the same procedure with the next group of drop-in visitors.

The international reputation of the doctor, as both a healer and a character, was further enhanced when adventurer and actor Michael Palin called on Dr Ho for his BBC “Himalaya” series, which aired in 2004. An earlier entry in the clinic’s guestbook — “Interesting bloke, crap tea” — had been attributed to Palin’s fellow Monty Python colleague John Cleese, but it was later debunked as the mischievous work of a visitor from Surrey, England.

“He was a charming man to spend time with, and from what I can gather, had a good, full life, ” Palin emailed me from the U.K. after I told him of the doctor’s death in September.

Dr. Ho had advised Palin to avoid pork, among other health tips. “Be careful of what you put in your mouth,” he often told visitors, as he dispensed herbal cures and lifestyle wisdom. As well as extolling the benefits of using herbs to treat long-term conditions, Dr. Ho advocated living simply; avoiding alcohol, smoking, and too much meat, particularly pork; and reducing salt.

“Simple food, simple life. But most of all, be happy. Optimism is the best medicine, I am sure,” he told those who crowded into his clinic. “No stress. No worry. Be happy. It is the truth.”

An irrepressible workaholic, both he and his wife remained active, working seven days a week. “I’m old, but I’m happy,” he would say. “And I am very strong.” He would let guests feel the softness of the skin on his forearms, saying, “See, like a baby’s skin.”

Despite the hardships and suffering of his early life, he was confident he would live a long life, and invited visitors to return again for his 100th birthday. “I hope to see you again, when I’m 100,” were his parting words, along with his blessing, “I wish you peace and good health.”

It was only since the turn of the century that the doctor gained more recognition and commendation within China. Overseas, he was already listed in many international who’s who biography lists of famous people, celebrities, and medical pioneers.

After his death on August 31, the provincial medical journal noted the high medical standards and exquisite medical skills of “the Good Doctor of the Snow Mountain.” “Proficient in foreign languages, he made a unique contribution to the promotion of Chinese medicine,” the journal proclaimed. A recent documentary on Chinese television, “Materia Medica China,” noted that Dr. Ho was influential in spreading Chinese medicine culture around the world.

The legacy of the doctor will be remembered fondly around the world by his tens of thousands of visitors and friends. His clinic, along with a herbarium and tribute to the Flying Tigers and Dr. Ho, is maintained by his son. He Shulong’s son, Dr. Ho’s grandson, is also a doctor.

Dr. Ho didn’t quite make it to his 100th birthday, but he lives on: as a legend, a character, a pioneer, a promoter, a wise man, a quirky wizard, and a healer.

Keith Lyons lived in Lijiang for a dozen years, founding the Lijiang Earthquake Relief Project in 1996 and establishing the travel operation Lijiang Guides. He was a longtime friend of Dr. Ho.