Concerns about immigration remain a focal point in both American and European politics. The competing demands in Taiwan are familiar to those watching immigration debates elsewhere: the need for workers, especially unskilled workers, for jobs locals cannot or are unwilling to fill versus concerns about the political and social costs of migration. Meanwhile, immigrant workers in Taiwan frequently protest labor conditions.

According to the Ministry of the Interior’s National Immigration Agency, of the over 770,000 foreign residents in Taiwan, more than 90 percent are from Southeast Asia, and predominantly from Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines. In 2017, Taiwanese married more Southeast Asian partners than partners from China. Despite government policies over time to increase ties with Southeast Asian countries as a means to be less economically ties to China, and discussion on immigration policy to encourage Southeast Asian skilled labor immigration to counter Taiwan’s brain-drain, such efforts have not been without controversy. For example, in December 2018 several Taiwanese universities were accused of skirting labor laws by recruiting Southeast Asian students for factory work under the questionable guise of internship programs, although many Indonesian students deny these claims. Another scandal concerned the disappearance of 152 of 153 Vietnamese tourists that arrived in Kaohsiung, with only 67 located by early January, raising concerns of human trafficking.

Concerns about immigration largely focus on the often interrelated perceived criminal, economic, and cultural threats. For example, considerable research focuses on the ethnicity of immigrants vis-à-vis the citizen population and its impact on perceptions of market competition and negative views more broadly of immigrants (see here, here and here). In terms of individual-level factors, higher education consistently corresponds with more favorable views of immigration, while other scholars have found living abroad and contact with other cultures also positively impacting immigration views. Meanwhile, limited scholarly work addresses both communities in Taiwan (see examples here and here).

I wanted to unpack whether evaluations of immigration differed in Taiwan based on two factors: immigration in general versus Southeast Asian immigration specifically and whether the focus is on skilled immigration. Considering that academics, political advisers, and marketers have long identified the role of framing and priming in influencing public perceptions, we would expect that relatively small differences in how immigration is presented would influence support, just as previous research on Taiwanese perceptions of free trade agreements, refugees, same sex marriage, diplomatic recognition, and President Donald Trump has shown.

If Taiwanese implicitly or explicitly distinguish between types of immigration, this should be evident when comparing perceptions of similarly worded survey questions. In particular, one would expect that if Taiwanese view Southeast Asian immigration as a criminal, economic, or cultural threat, a focus on Southeast Asian immigration should elicit stronger opposition than when asked about immigration in general. Similarly, if the concern is about unskilled labor and thus competition for jobs, a focus on skilled labor immigration would be expected to generate more positive views on immigration.

To address this, I conducted a web survey in November of 1,000 Taiwanese, surveyed via PollcracyLab at National Chengchi University. Respondents were randomly assigned to respond to one of four versions of a question regarding immigration and asked to evaluate it on a five-point Likert scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree):

Version 1: Taiwan should encourage immigration

Version 2: Taiwan should encourage immigration of skilled workers

Version 3: Taiwan should encourage immigration from Southeast Asian countries

Version 4: Taiwan should encourage immigration of skilled workers from Southeast Asian countries

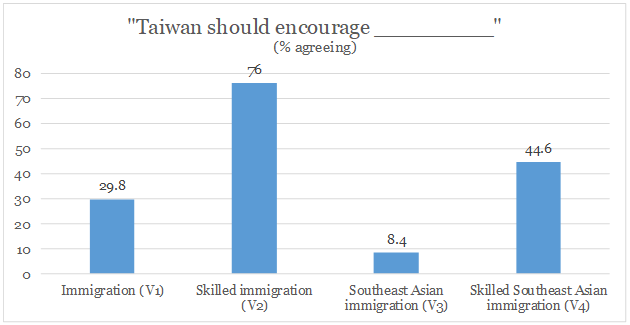

The figure below shows the percentage of Taiwanese surveyed agreeing to each version of the survey. For simplicity, I combined those that agreed and strongly agreed. Here we clearly see that Taiwanese are more supportive of encouraging immigration when framed as skilled immigration, a 46.2 percent increase from the baseline of Version 1. However, support decreases by 21.4 percent from the baseline when simply focusing on Southeast Asian countries. Furthermore, while the version focusing on skilled Southeast Asian immigrants increased support compared to the baseline by 14.8 percent, this is still far lower (31.4 percent) than support for skilled immigrants in general.

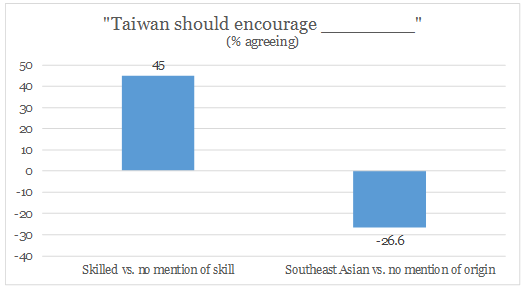

The figure below further makes it clear that Taiwanese are more favorable to skilled labor immigration and less favorable to Southeast Asian immigration. Support increased by 45 percent when skilled labor was mentioned compared to no mention at all, while support for immigration decreased by 26.6 percent when the focus was on Southeast Asian immigration rather than immigration in general.

Additional analyses controlled for a myriad of factors — age, gender, education levels, household income, political ideology, and party identification — with consistent results as those shown above. Overall the results suggest the extent to which Southeast Asian immigration generates a visceral reaction, one that is only partially overcome when the focus is redirected to skilled labor. However, it is unclear how to rectify these biases. With several hundred thousand children of Southeast Asian immigrants already in the Taiwanese elementary school system, ignoring this issue will only create larger identity concerns for Taiwan in the future.

Timothy S. Rich is an associate professor of political science at Western Kentucky University. His research focuses on public opinion and electoral politics in East Asian democracies.