India’s Defense Research and Development Organization carried out a failed first attempt to destroy a satellite in low-earth orbit on February 12, The Diplomat has learned. The test took place from Abdul Kalam Island off the eastern coast of India.

According to U.S. government sources with knowledge of military intelligence assessments, the United States observed a failed Indian anti-satellite intercept test attempt in February. The solid-fueled interceptor missile used during that test “failed after about 30 seconds of flight,” one source told The Diplomat.

That test is believed to have been India’s first-ever attempt at using a direct-ascent, hit-to-kill interceptor to destroy a satellite—a feat that was completed successfully on March 27, when Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced a successful test in a national address. The first Indian anti-satellite test was dubbed “Mission Shakti.”

It is unclear if the February 12 failed test attempted relied on the same missile and interceptor as the successful March 27 test. According to one U.S. government source, the Indian side had notified the United States of its intent to carry out an experimental weapon test in early February, but without confirming that it would be an anti-satellite test. “They gave us a vague heads up,” the source said.

The first failed Indian test, however, provided enough information for U.S. military intelligence to conclude that New Delhi was attempting an anti-satellite test using a new kind of direct-ascent kinetic interceptor.

India’s anti-satellite test resembles tests conducted in 2007 and 2008 by China and the United States respectively. All these tests have used the kinetic force of an interceptor to collide with a satellite moving rapidly in low earth orbit, destroying it completely and creating orbital debris.

India’s successful intercept took place at an altitude much lower than China’s 2007 test, which generated more than 2000 pieces of significant debris, hundreds of which will remain in orbit for decades. The approximately 282 km altitude of India’s intercept was closer to the 240 km altitude of the United States’ 2008 shootdown of the USA-193 satellite.

U.S. government sources that spoke to The Diplomat were unable to confirm if Microsat-R, the 740 kg satellite India had launched on January 25 and shot down on March 27, was the intended target for the February 12 test attempt. Microsat-R was the target satellite shot down during the March 27 test.

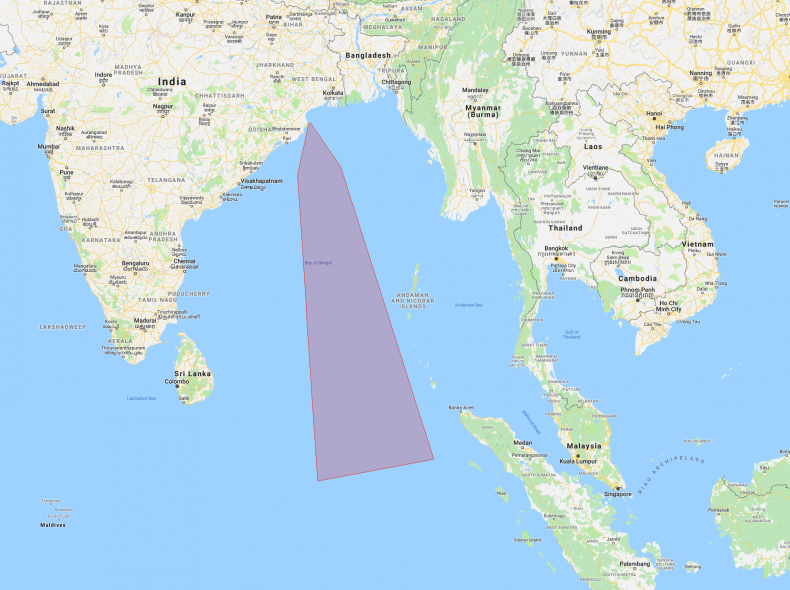

However, a Notice to Airmen (NOTAM) issued by Indian civilian authorities with effect between February 10 and February 12 demarcated a restriction zone off the eastern coast of India that matches the restriction zone described in another NOTAM issued ahead of the March 27 test attempt, suggesting that the very same satellite was the intended target. The February NOTAM warned of the “launching of experimental flight vehicle,” but did not specify that any low earth orbit objects would be held at risk.

Indian NOTAM with effect between February 10, 2019, at 5:15 a.m. to February 12, 2019, at 6:45 a.m..

Following India’s successful anti-satellite test on March 27, the U.S. State Department released a statement noting that it “saw PM Modi’s statement that announced India’s anti-satellite test.” The statement added support for a strong U.S.-India relationship, noting that “As part of our strong strategic partnership with India, we will continue to pursue shared interests in space and scientific and technical cooperation, including collaboration on safety and security in space.”

“The issue of space debris is an important concern for the U.S. government. We took note of Indian government statements that the test was designed to address space debris issues,” the statement continued. In the aftermath of the test, U.S. Strategic Command began tracking more than 200 debris objects.

The United States is still assessing the total scope of the debris created by the Indian test. India has claimed that it expects all debris from the March 27 test to burn up in the earth’s atmosphere in 45 days.

A Pre-Election Controversy

Politically, had the first attempted Indian anti-satellite test succeeded, Modi might have avoided the scrutiny that came with a national address to announce the March 27 successful test so close to the opening of polling for India’s 2019 general elections, which will see some 900 million Indian voters select candidates for the lower house of India’s bicameral parliament.

Beginning on March 10, the Indian Election Commission put in place the Model Code of Conduct, which restricts the kind of policy announcements the incumbent government can make in an attempt to prevent unfair attempts to seize an electoral advantage before the elections.

Indian opposition parties claimed that Modi’s announcement of the anti-satellite test was a violation of the code. Two days after his announcement, the Electoral Commission determined that Modi had not violated the code of the conduct with his national address announcing the successful test.

The test attempt in early February also pre-dated the Pulwama terror attack on February 14, which killed 40 Indian paramilitary personnel and precipitated a major crisis with Pakistan that culminated in late February with Indian air strikes on Pakistani soil.