The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between two South Caucasian republics, Azerbaijan and Armenia, is already over 30 years old. Negotiations toward a settlement face a stalemate that appears difficult, if not impossible, to overcome. The conflict, which has roots dating back to the early 20th century, was restarted violently in late 1980s at the time of the collapse of the Soviet Union when Armenia, seizing the opportunity created by the regional geopolitical turbulence, established its control over 20 percent of the internationally recognized territories of Azerbaijan. Since the 1994 ceasefire agreement brokered by Russia, the sides have been trying to reach a peace agreement through negotiations brokered by the OSCE’s Minsk Group, co-chaired by Russia, the United States, and France.

The existing deadlock in the negotiations begs the question of whether China, an increasingly more assertive global actor that has never attempted to undertake a mediating role in the conflict, can push Armenia and Azerbaijan to resolution. Doing so would also expand the economic value of the entire South Caucasus region for China’s global projects. China’s expanding economic engagement with the two sides of the conflict and its global conflict resolution efforts suggest that it actually can push for a breakthrough – if Beijing chooses to try.

China’s Rising Economic Power in the South Caucasus

The South Caucasus was a “low-priority” region for China for the most part of the region’s post-Soviet history. By the early 2000s, the EU and Russia had already initiated comprehensive engagement with the regional countries in nearly all spheres, but China maintained a low profile in the political and economic map of the region. Nor did the South Caucasian countries, which were more focused on either the market of the post-Soviet countries or that of Europe, demonstrate a real interest in China.

The region started to gradually capture Beijing’s attention in the wake of the launch of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013. The growing desire of the regional countries to attract Chinese investments accelerated this process. The region’s attractiveness was also affected by the economic downturn in the economies surrounding the South Caucasus (Iran, Russia, and Turkey), which created more room for the influx of China’s economic influence.

Another factor that played a positive role in this context was the realization of big transportation projects in the South Caucasus such as the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway and Alat Free Economic Zone created within Alat International Sea Trade Port. These projects boosted the region’s viability for becoming a hub on the China- Europe trade route. Although 96 percent of the trade between China and Europe is being conducted via the ocean routes and the remaining 4 percent is covered by the Trans-Siberian route (the “Northern Corridor), a number of factors encourage both China and Europe to invest in the Trans-Caspian International Transport Corridor (TITR) project, also known as the “Middle Corridor.”

The Middle Corridor appears to be 2,000 km shorter and thus more economical and faster compared to the Northern Corridor. It also runs through more favorable climate conditions. The Corridor has also some advantages compared to the sea route, as it shortens the travel time by one-third, or 15 days.

The strained relationship between the EU and Russia is another factor encouraging China and the EU to invest in alternative routes that might come in handy when the Northern Corridor cannot be employed. Brussels’ decision to invest 13 billion euros for better connectivity and stronger growth in the six Eastern Partnership countries (e.g. Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, the Republic of Moldova, and Ukraine) demonstrates growing European interest in the Middle Corridor.

These developments provided favorable ground for China’s deeper engagement with the three countries of the South Caucasus. The recent mutual official visits between the South Caucasian countries and China have been a great impetus for this engagement.

In the course of the visit of Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev to Beijing to attend the second Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation, which took place in Beijing on April 25–28, 2019, Azerbaijani companies successfully concluded 10 agreements, cumulatively worth $821 million, with Chinese companies. This was an overwhelming push to the bilateral relationship between the sides as China had invested only $779 million in the Azerbaijani economy in the entire post-Soviet period. This development is in line with the overall growing cooperation between China and Azerbaijan, which also saw the bilateral trade turnover rise from a mere $1.5 million in the early 1990s to $1.3 billion in 2017 (around 6 percent of Azerbaijan’s overall foreign trade).

Similar progress has been made also in China’s economic relationship with Georgia. The two countries have enjoyed a free trade agreement since January 2018. Prospects look bright for the future as well. Last month, for the first time in 23 years, a Chinese foreign minister visited Tbilisi. Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s visit to Georgia on May 24, according to the Georgian Foreign Ministry, focused on “the development of cooperation in the fields of trade, logistics and transport.” Wang’s visit followed Georgian Minister of Infrastructure and Regional Development Maya Tskitishvili’s trip to Beijing, where she attended the second Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation. In the course of her visit, she signed an agreement on cargo and passenger transportation with Chinese Minister of Transport Li Xiaopeng, which the Georgian minister called a “huge step forward” in the bilateral relationship.

Armenia, the smallest economy of the region, has also achieved progress in its relationship with Beijing. Yerevan has long sought to draw Chinese investment to the establishment of the “Persian Gulf–Black Sea” multimodal transport and transit corridor to link Iran with Europe via Armenia and Georgian Black Sea ports. The project is seen in Armenia as the only resort to overcome the constraints posed by the country’s landlocked geographic location and the closed borders with Azerbaijan and Turkey, a direct result of Armenia’s occupation of the Nagorno-Karabakh and surrounding regions of Azerbaijan.

Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan’s visit to Beijing to attend the Conference on Dialogue of Asian Civilizations in May 2019 has been a boost for the bilateral relationship. In the course of the meeting, Chinese leader Xi Jinping expressed China’s readiness to invest in the construction and implementation of transportation and infrastructure projects in Armenia, although no concrete plans were made public.

Thus, although the South Caucasus has a significant chance to become a hub with dazzling economic potential on the transportation route between Europe and Asia, due to the intraregional conflicts the three countries of the region cannot realize their real potential. The remaining and often alarming threat of a sudden escalation of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict not only ruin the lives of the people of Armenia and Azerbaijan but also generates dangers for foreign investments. China, as an increasingly more assertive global actor involved in economic cooperation with the regional countries, can play an impactful role in the settlement of this conflict.

China’s Increasing Conflict Resolution Efforts

Beijing’s aspiration to expand its global economic ties had the knock-on effect of forcing the Chinese leadership provide fundamental security conditions for Chinese citizens and companies internationally. This generated a clear-cut shift in China’s foreign policy principles, which had traditionally insisted on disengagement from conflict resolution abroad.

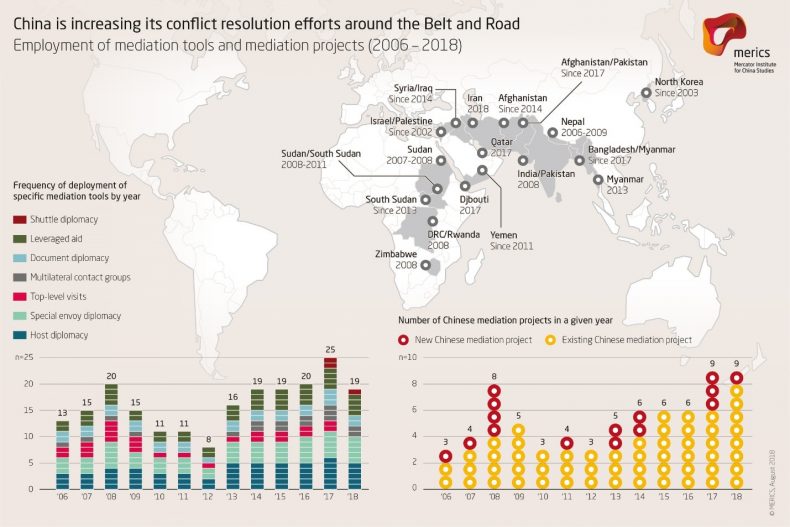

The launch of the BRI was a powerful push for this transformation. The project might encounter a drastic failure if the necessary political stability in the target countries cannot be maintained. A 2018 study by the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS) concluded that since 2013, when the initiative was announced, China has demonstrated a much more active role in the resolution of numerous conflicts along the route that the BRI traverses:

Recent years have seen significant changes in China’s international mediation activities. In countries like Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Syria, and Israel, among others, diplomats from China increasingly engage in preventing, managing, or resolving conflict. In 2017 Beijing was mediating in nine conflicts, a visible increase compared to only three in 2012, the year when Xi Jinping took power as General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Source: MERICS.

Such a rise in Chinese mediation of international conflicts creates hope for the constructive engagement of China in the resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. As the authors of the Mercator Institute study rightfully flesh out, not only would the resolution of interstate conflicts along the BRI route provide better security conditions for Chinese investments but it would also help Beijing to craft an image of itself as a responsible global power. This perspective is in a perfect line with Xi’s political agenda, as he has promised to turn China into a great power by 2049, the centennial of the People’s Republic.

The expanding economic bonds between the regional countries and China gives Beijing important leverage to affect the conflicting sides and push them into a quick resolution. In particular Armenia, a country that faced massive political and economic difficulties due to the prolongation of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, desperately needs Chinese investment for economic revival. Yerevan cannot fullfil its economic plans otherwise; the “Persian Gulf – Black Sea” multimodal transport and transit corridor alone could cost around $3 billion, a significant part of Armenia’s $10 billion annual GDP.

The conflict resolution process has the potential to be revived through Chinese-style mediation, which is traditionally based on high-profile engagement with the top levels of governments through official visits and via special envoys. The innovative strategies brought about by the European and American involvement, which included so-called Track II diplomacy promoting contacts between the peoples and civil society of the two countries, has so far failed to produce tangible results. Therefore, a new approach to the resolution process brought by Chinese mediation could prevent a potential escalation of the conflict and help reach a peace agreement between the sides.

The potential of Chinese mediation is also bolstered by the common interest shared by both Europe and China to maintain stability and build lasting peace agreements in the regions between the two. The European Union, although largely unsuccessful, but has spent a large amount of resources and made numerous efforts to encourage the sides to make compromises to achieve a common ground. These efforts could gain a new life with cooperation between Europe and China.

Importantly, the expanding cooperation between China and Russia in a wide range of global issues can also play a positive role in this context. Although Russia has traditionally opposed projects that seek to bypass it, international conditions are pushing the Kremlin to cooperate with Beijing, which might bode well for the settlement of the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict.

Dr. Vasif Huseynov is a research fellow affiliated with the Center for Analysis of International Relations and lecturer at Khazar University in Azerbaijan.