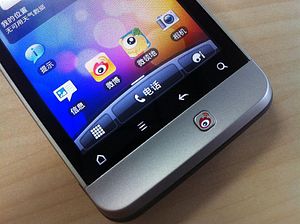

In late May, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) opened its first official account on Sina Weibo, the Chinese equivalent of Twitter. It was a clear indication that the Chinese government realizes the need to step up its public diplomacy activities to build up the country’s image through social media.

The new Weibo account comes after MOFA opened an account on WeChat, China’s most popular social media and messaging platform, last year. This comes in addition to an array of other activities already undertaken by MOFA, including organizing lectures, conferences, internet discussions, and opportunities for citizens to visit the ministry.

MOFA’s foray into social media is part of its expansion of public diplomacy, especially targeting the domestic audience but also including the Chinese diaspora worldwide. The effort seems to have been well-received by the Chinese public.

Public Diplomacy and China

Public diplomacy, broadly understood, is a country’s efforts to engage and interact with the general public in foreign countries to manage opinion in favor of the country. It has increasingly become a necessary imperative in many countries’ diplomatic toolkit, irrespective of the country’s size or economy. It is essentially a communication-driven practice, which has seen a spurt with the revolutionary expansion of the internet and social media.

The internet and social media have become a mainstay in the management of public perception and public opinion, mainly because they enable real-time engagement and communication. But with increasingly disappearing national and international boundaries, public diplomacy activities through social media target not only a foreign audience but increasingly the domestic public as well.

Although China has made a lot of investments and efforts in public diplomacy activities, MOFA kept itself aloof from social media platforms until it made its debut on WeChat as late as last year. It is strange indeed, especially as a rising power that is more conscious of its image in the international system, that the Chinese government and bureaucracy did not take social media seriously. This is even more striking because the government has pursued an array of public diplomacy activities by other means, such as building Confucius Institutes, cultural, and language promotion, and educational exchanges.

What Prompted the Latest Move?

This foray onto social media must be seen in the light of a number of variables, both domestic and international. China is making strenuous efforts to explain its viewpoints to the world in order to counter what China sees as rising prejudices, misunderstanding, and misconceptions about the country politically, ideologically, economically, and militarily.

China has always complained about the perceived targeting of China by the Western media, which Beijing says conveys a distorted picture of the country to the world without showing the positive developments. A recent example would be Western media interest in human rights violations of Uyghur Muslims, which caught international attention, and the perennial lack of free speech and expression more generally. China perceives it needs to disseminate positive national image as a counter strategy. It is a major challenge for China to fend off such perceived denigration and requires massive support from the domestic population for China’s foreign policies.

However, the constant stream domestic issues is another cause of great concern for the government. Domestic turbulence can severely damage the prospects of China’s big ambitions abroad. Recently, President Xi Jinping urgently summoned hundreds of officials to Beijing to lecture them about efficiently managing public discontent arising from a number of issues such as trade, foreign policy, corruption, and unemployment. Xi declared that any mistakes or subdued responses from officials faced with such dangers will be not be taken lightly.

He is reported to have told the gathering, “Globally, sources of turmoil and points of risk are multiplying.” Xi later added that “the [Chinese Communist] Party is at risk from indolence, incompetence, and of becoming divorced from the public.” In this warning to officials, many read a tacit admission from Xi that his government is losing support in the domestic sphere.

Domestic issues indeed cannot be separated from international relations and global politics. As Elizabeth C. Economy, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York, told the New York Times, “Beijing is confronting significant pressure from the international community over its political and business practices that only adds to its difficulties in dealing with its domestic issues.”

These circumstances help explain MOFA’s recent social media push. Opening a social media platform is intended to bolster the government’s positive image through dialogue and interaction with the public. This can certainly boost its image in the domestic realm, which will have implications at the global level.

Perennial sources of discontent like corruption and the possibility of economic turmoil could spark wide public resentment. The CCP is well aware that it must be prepared for the worst possible scenario. Therefore, an increasingly inward turn in its public diplomacy is inevitable, as domestic public support is crucial to bolster tough economic and foreign policies.

Another reason behind MOFA’s attention to social media could be China’s goal to interact more with the Chinese diaspora overseas. At a February 2017 national work meeting on overseas Chinese, Xi called for “closely uniting” with the Chinese diaspora in building up the country. The Chinese diaspora, numbering about 60 million, are spread all over the world, with the majority living in Asia. Many of them use the same social media platforms popular in China, especially WeChat.

In recent years, China has been seeking less official channels to make its concerns heard. In that context, more civil society participation can strengthen alternative channels to pursue China’s national interests. Therefore, the role of domestic constituents becomes increasingly important, and proactively engaging in domestic public diplomacy must be seen as a necessary long-term strategy.

Muhsin Puthan Purayil is a Ph.D. Candidate in Political Science at University of Hyderabad, India. His research interests include international relations, India’s foreign policy, and diplomacy.