Over the past few weeks, more details have been surfacing about allegations of a Chinese naval outpost in Cambodia. As such specifics continue to emerge in the coming months, it is important to consider what the implications of such a development would have for not just Beijing’s presence in the Southeast Asian state, but its broader regional influence and its effects on the wider balance of power in Southeast Asia and the Asia-Pacific.

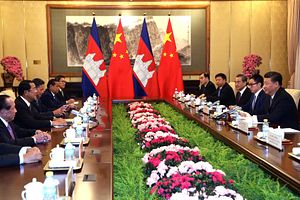

As I have noted before in these pages, while fears about an increased Chinese military presence in Cambodia have been intensifying over the past few years, they reached new heights as of late last year when, in November, U.S. officials had raised concerns about China building a dual use facilities in Cambodia and Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen had received a letter U.S. Vice President Mike Pence on this as well.

Over the past few weeks, a new round of scrutiny has been emerging on this issue. Last month, the United States said Cambodia had suddenly turned down an offer to repair a training facility and boat depot at Ream Navy Base, leading the Pentagon to deliver a June 24 letter seeking clarification on whether there were plans for hosting Chinese military assets there. And over the weekend, the Wall Street Journal, citing anonymous U.S. and allied sources, said that China had signed a secret agreement in the spring that gave China exclusive rights to part of Ream Navy Base for 30 years, with automatic renewals every decade after that which would allow Beijing to post personnel, weapons, and warships there.

Both China and Cambodia continue to deny the existence of a full-fledged base, and Cambodia in particular has maintained that a base would violate its constitution. But as I have noted before, the most likely scenario we are likely to see play out in such cases is that both Beijing and Phnom Penh would continue to publicly deny speculation about a base per se but also quietly develop various locations as dual-use civilian military facilities that essentially accomplish the same objective: providing privileged access and staging grounds for personnel and vessels. Given that, rather than fixating on labels and rhetoric, it is more useful to look at the tangible implications and realities of a heightened Chinese military presence there along these lines.

Those implications deserve noting from at least three different lenses. First, a new China naval outpost in Cambodia would matter because of the observed negative effects that previous security arrangements have already generated for regional stability. Indeed, it is important to remember that even leaving naval outpost fears aside, China has already been making other significant military gains in Cambodia that neither side has denied, including new exercises and sales of military equipment, that have coincided with losses for other countries, be it Cambodia’s shifting South China Sea position that has further undermined ASEAN unity or suspension of military ties with Western states that heighten zero-sum thinking on security alignments and raise further suspicions about what Beijing and Phnom Penh have in mind.

Given that a new, secretly negotiated Chinese naval outpost would be just the latest sign of Beijing’s rising security role in Cambodia which has already generated some negative regional effects, one can expect these consequences to heighten both in terms of perceptions and reality. And while countries including Cambodia are certainly free to choose their own alignments, it is also only natural that the nature of those alignments is of concern to other regional states in Southeast Asia and beyond, especially if they come at their expense and to the detriment of wider stability.

Second, a new Chinese naval outpost in Cambodia matters because would be yet another sign of the further development of Chinese security partnerships in Southeast Asia, which comes with its own challenges. As I have detailed extensively, including in a new report for the Wilson Center, episodic attention to individual Chinese inroads in countries such as Cambodia can obscure a bigger picture where Beijing has been systematically building the outlines of a wider regional security architecture of its own through a series of exercises, dialogues, and facilities, with Southeast Asia being the region where this has manifested most clearly. While these alignments may partly be a consequence of China’s rising influence, they also raise concerns, including with respect to transparency, exclusivity, and regional stability.

Seen from that perspective, a naval outpost in Cambodia is significant in that it constitutes the first opening for China for the facilities component of its strategic partnerships in Southeast Asia as a subregion. It would also provide Beijing with a platform to develop other aspects of this effort, including exercises and naval visits, in line with a trend we have seen thus far which is an increasing level of complexity and institutionalization of these arrangements.

Third, a new Chinese naval outpost in Cambodia matters because it could affect the wider balance of power at play in Southeast Asia and the wider Indo-Pacific region. While it is certainly true that a Chinese naval outpost in Cambodia is not quite as strategic as locations could be in other Southeast Asian states, it is nonetheless not without significance. An outpost there would provide China with a key positional advantages in mainland Southeast Asia, in addition to other access arrangements it is striking with regional states in the subregion and other facilities it has in other parts of the Indo-Pacific, be it in Gwadar or on its artificial islands in the South China Sea.

In that sense, this could have important implications for the balance of power. Most clearly and immediately, a Chinese naval outpost in Cambodia would affect the balance of power in mainland Southeast Asia, a region which has previously been riven with tensions and conflict. In particular, Vietnam and Thailand, which have both seen themselves as leaders in mainland Southeast Asia, would be concerned about having such a Chinese facility so close to their borders, and this could lead them and other actors to take reciprocal actions that would further affect regional stability (indeed, Vietnam has already shown some of this concern with respect to the Chinese development of institutions in the Mekong subregion). In addition, considering that the gradual development and networking of such Chinese facilities can over time complicate U.S. military planning when it comes to broader Asian flashpoints as well, such as Taiwan and the South China Sea, they could have additional implications for the Asian balance of power more generally as well.

To be sure, as has been the case with some recent China-Cambodia military arrangements as well, details are still unclear about the exact nature of the facility, including what exactly will be built, what it will be used for, and how it will evolve given the increased scrutiny we are seeing. Nonetheless, these big picture implications are helpful to keep in mind as we see more details continuing to filter in in the future on this front.