Why did Imperial Japan fail to prepare for the threat of submarine warfare, and what lessons can we take for how military organizations learn in the future?

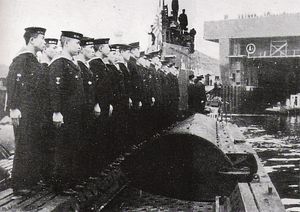

Despite close contacts between the Royal Navy (RN) and the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) during World War I, and a strategic situation with distinct similarities, the IJN in World War II largely failed to adopt the strategic approach to anti-submarine warfare (ASW) that the RN had pioneered in 1917 and 1918. While the Royal Navy adapted to anti-commerce submarine attacks and the British war effort survived, Japan was effectively strangled by a U.S. submarine campaign.

At Strategy Bridge, Phillip Ramirez proposes an answer that concentrates on civil-military relations. In both cases, the services adopted offensive, “Mahanian” (something of a misnomer) strategies for winning the war through forcing decisive battles. When the course of war denied such opportunities, each service was faced with the unforeseen problem of a long-term anti-commerce campaign. Civilian supremacy in the United Kingdom, he argues, forced the Royal Navy to adopt commerce protection measures, while the relative inability of Japanese civilian leadership to settle inter- and intra-organizational disputes within the Japanese military fatally delayed the development of anti-submarine capabilities.

Indeed, Japan’s anti-submarine problems were even more extensive that Ramirez documents. Even in World War I, the Royal Navy appreciated the threat of the submarine and dedicated considerable resources to ASW force protection, if not commerce protection. Partially in consequence, despite a few critical failures (the loss of three old armored cruisers in 1914, for example) the Royal Navy managed to almost entirely resist repeated attacks upon the capital ships of the Grand Fleet. In World War II the RN did somewhat less well, losing two battleships and three fleet carriers to submarine attack. But the Japanese record was even worse, with a battleship, eight carriers, and several heavy cruisers lost to subs during the conflict. The IJN’s inability to deal with submarines is even more puzzling given the complete inadequacy of U.S. submarine doctrine and equipment in the first years of the war, and the counter-force (Mahanian, in reality) submarine doctrine that the Japanese themselves adopted before the war.

Ramirez allows that the argument about civilian oversight is only part of the story. The relative material position of the Royal Navy and the merchant marine of the United Kingdom prior to both wars was distinctly superior to that of the Japan in 1941, meaning that the British had breathing room to make and learn from mistakes that the Japanese simply couldn’t afford. Moreover, the Japanese strategic class believed that any war that could not be won by short, decisive battles simply could not be won; there was no point in dedicating resources to a long war when victory under such circumstances was impossible.

Still, the contrast between Japanese and British preparation is useful and instructive for helping us think about how military organizations react to adversity. It’s also helpful for examining how navies that organize themselves on self-consciously “Mahanian” lines approach the problem of anti-submarine warfare. My next column examines these questions in some greater detail.