A new wave of populist governments with autocratic tendencies have come into power in Latin America, ending the left-leaning “pink tide” that swept across the region in the early 2000s. These new governments cast shadows over China’s comprehensive strategic partnerships in the region.

From December 2018 to January 2019, populist leaders took office in Mexico and Brazil. Worse, in Venezuela the failure of Juan Guaidó to dislodge Nicolás Maduro from power has accelerated the country’s economic implosion. All these laid the groundwork for possible return to power of former President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner in Argentina. With the three largest economies in Latin America destined for further mismanagement, the prospects for growth in the region are dim. Consequently, China’s strategic partnerships in the region are facing an acid test.

The first shadow comes from Mexico’s Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), inaugurated on December 1, 2018. On June 19, Mexico became the first country to approve the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). Importantly for Beijing, there is a “poison pill” clause in the USMCA regarding China. If any of the three countries in the USMCA enters a trade deal with a “non-market country,” the other two are free to quit USMCA within six months and form their own bilateral trade deal. While the fate of USMCA lies with the U.S. House of Representatives, Beijing is concerned that similar “poison pill” clauses may begin appearing in other trade agreements in the region.

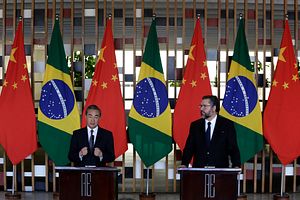

A second shadow is cast by Jair Bolsonaro, inaugurated as Brazil’s president on January 1. Bolsonaro’s rise to power and subsequent friendliness toward Washington may have come as a surprise for Beijing. Where previously China and Brazil enjoyed relatively friendly relations, Bolsonaro has been decidedly more antagonistic toward China and pro-Washington, going so far as to call off a June 20 meeting with Chinese president Xi Jinping during the G-20 summit in Osaka, Japan.

Bolsonaro has pivoted away from China with U.S. encouragement and promises of more trade. Before the new president’s inauguration, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo applauded Bolsonaro for “standing up for Brazilian sovereignty in the face of China’s predatory trade and lending practices.” Now, more than six months after Bolsonaro’s inauguration, President Donald Trump announced that the United States and Brazil will work toward a free trade agreement. All of this works directly against China’s strategic aspirations in Latin America.

President Nicolás Maduro of Venezuela is responsible for the third shadow. Maduro, who took the oath on January 10, 2019 for his second term, has been confronting opposition leader and self-declared interim president Juan Guaidó since January 23. But the danger Venezuela’s descent into chaos poses to Chinese strategic interests has long been obvious for Beijing.

Economically, Venezuela has not been able to repay Chinese loans. China lent Venezuela approximately $60 billion between 2007 and 2017 under oil-for loan deals. And in December 2017, Sinopec USA, a subsidiary of Chinese oil and gas conglomerate Sinopec, sued Venezuela’s state oil company PDVSA in a U.S. court. Last year China balked at making new financial commitments because of an outstanding bilateral debt reportedly in excess of $19 billion.

Politically, China is being dragged into the internal matters of a foreign country. China now must pay close attention to the vagaries of politics in Venezuela, with Beijing’s actions potentially setting off cascade effects that can damage China’s interests. For example, the Inter-American Development Bank cancelled its 2019 annual meeting in Chengdu, China, because Beijing refused to issue a visa to Guaidó’s representative, Harvard economist Ricardo Hausmann. Given these volatile dynamics, it will be difficult for China to continue pursuing its strategic initiatives without a recalibration of priorities and policy.

Latin America’s turn away from China has drawn a new ideological map for its international relations. During the “pink tide” era, left-wing governments in South America preferred “South-South cooperation” over ties with Europe or the United States. This preference is a key reason why China became Mercosur’s largest single trading partner (and the second largest for Latin America as a whole). Although the EU remains the largest investor in Latin America, Chinese investments and loans to the region have rapidly increased.

But it is increasingly unclear whether the new populist governments will encourage free trade. Some critics have charged Argentina and Brazil with using Mercosur as a way to shield domestic industries from international competition. The criticism levied by Oliver Stuenkel, an assistant professor at the Getulio Vargas Foundation in Sao Paulo, is that Mercosur often “is less about opening up but actually about protecting Brazilian and Argentine industries from global competition.” Mercosur countries have also failed to coordinate their trade policies toward third countries. For instance, Brazil unilaterally imposed anti-dumping restrictions on steel imports from China in 2011. Indeed, as far back as 2012 The Economist recognized that “politically negotiated exceptions to the bloc’s rules became the norm.”

Perhaps as a result of rising protectionist winds, the Latin American region saw the largest forecast downgrades from the IMF, with growth remaining low in Mexico and Brazil this year. Argentina, meanwhile, is expected to recover slowly from last year’s crisis.

For its part, China is pressing forward with its plans to deepen ties with Latin America. At the second Forum of China and Community of Latin American and Caribbean States ministerial held in January 2018, both sides agreed to an updated cooperation plan extending through 2021. China also invited Latin American countries to participate in its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which is focused on infrastructure development in various regions around the world. Currently 16 Latin American and Caribbean countries are participating in the BRI. However, if China cannot re-establish its relations with its most important strategic partners in Latin America, those efforts may bear little fruit for Beijing.

Antonio C. Hsiang is Professor and Director of the Center for Latin American Economy and Trade Studies, Chihlee University of Technology.