Argentina and Brazil are the largest economies in South America. They are both in the G-20, and Argentina has now been invited to join Brazil and other large developing economies in the BRICS group. They are both big commodity producers. They both have four decades of experience with democracy after years under harsh military dictatorship. They both have a fondness for telenovelas and have won a bunch of World Cups. And they both trade a lot with China.

But while Argentina has signed up to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Chinese President Xi Jinping’s signature program of massive lending to finance infrastructure building across the developing world, Brazil, a big recipient of Chinese foreign direct investment and a top supplier of raw materials to China, has stayed away. Why?

I argue that a country will not join the BRI unless it stands to gain significantly from joining – or lose significantly from not joining. Brazil, which has a more mutually dependent commercial relationship with China, has had more space to maneuver than Argentina, a country in perma-crisis and starved for hard currency.

The BRI was launched by Xi in 2013. In the program’s early years, Brazil was going through political chaos and a deep recession under the (mis)management of Dilma Rousseff, a leftist president who now leads the New Development Bank in Shanghai. Any foreign endorsement of Brazil’s troubled economy during the late Rousseff years, or indeed under her successor Michel Temer’s administration, would have been welcome.

Temer was followed by Jair Bolsonaro, a Sinophobe in the mold of Donald Trump, under whom any proximity to China was unthinkable. Since January 2023, however, Rousseff’s mentor, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (or Lula as he is known), is back in power (Lula was also president between 2003 and 2011). Lula visited China early in his term.

Brazil pursues a pragmatic no-values diplomacy, and Brazilian leaders are notorious for their nonchalant attitude toward congregating with nasty dictators, be it lending legitimacy to brutal regimes such as Cuba’s and Venezuela’s, or welcoming Iran and Saudi Arabia into the BRICS club.

Add to that the fact that Brazil really needs China. China has been Brazil’s largest trade partner since 2009, fuelled by Brazilian exports of soybeans, iron ore and petroleum. Under Bolsonaro alone, Brazilian exports to China rose from $63 billion in 2019 to $89 in 2022. Brazil is one of the few large economies that has consistently run a trade surplus with China. It is also a large recipient of Chinese investment and loans.

So it may be puzzling that, so far, Brazil has chosen to stay away from the BRI. The Brazilian Sinosphere was full of excitement about a potential announcement of Brazil joining the scheme during Lula’s visit in April 2023, but that was not to be.

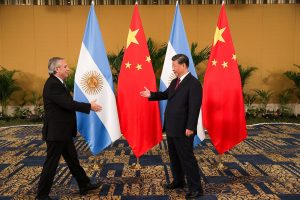

Contrast that with Argentina, which in February 2022 signed a memorandum of understanding to join the BRI.

From a foreign trade standpoint, Argentina is arguably less dependent on China than Brazil is. Argentina’s largest trade partner is not China but Brazil, its partner in the stagnant Mercosur trade bloc. Argentina’s inward FDI numbers picked up significantly in the three years to 2022, albeit from a low base. Recent data on Argentina’s FDI are hard to come by, but historically China has not been among the top investors into the country.

Argentina’s choice to join the BRI is probably explained by its dire financial circumstances. Argentina has been repeatedly rescued by the International Monetary Fund, with the last package in the amount of $44 billion approved in 2022. Still, in July it was announced that the IMF would lend Argentina money so Argentina could pay back the IMF itself. Argentina’s central bank has an agreement with China to swap local pesos for renminbi. It is public knowledge that Argentina has been tapping that swap line to pay back its international creditors, the IMF included.

Meanwhile, Brazil has more immediate choices, despite its heavy trade dependence on China. Brazil was a large recipient of Chinese loans in the heyday of China’s foreign lending program – some $31 billion according to the Dialogue Leadership for the Americas. But Brazil relies more on the domestic market for financing than it does on external creditors. Unlike Argentina, Brazil has not used its RMB swap line to support its accounts.

On top of that, Brazil has the comfort that China too depends on its exports of foodstuffs and raw materials. Having antagonized other large commodity exporters such as Australia, Canada, and the United States, China can ill afford to pick quarrels with Brazil, a country that has been a reliable supplier and diplomatic partner.

For all their lofty talks about principles, multilateralism, and developing countries’ desire to forge a new international order, Argentina and Brazil’s diverging choices about the BRI teach us two lessons. The first is about the pre-eminence of bargaining power. While Argentina has taken a beggars-cannot-be-choosers approach to its relations with China, Brazil capitalizes upon its position as a key friend to dictate at least some of the terms of the bilateral relationship.

Take this comparison to Europe, where Greece is a member of the BRI and has been a recipient of copious Chinese FDI into its port sector. The port of Piraeus has value for China as a foothold into European Union import logistics, regardless of Greece’s BRI membership. But Greece, like Argentina, was desperate for any outside endorsement of its economy fresh from the meltdown of 2009 and difficult euro negotiations of subsequent years. Greece took what was on offer.

Meanwhile, Italy, the only large developed economy to sign up to the BRI, is pondering its exit from the scheme (and risking China’s wrath for ditching it). Italy realizes it hasn’t gained much from the BRI, other than its G-7 partners’ suspicions. Unlike some of the BRI’s supposed benefactors in Africa, Italy is not reeling from too much debt, but is deterred by the more prosaic fact that BRI projects haven’t materialized at all.

This brings us to the second lesson: the limits of Chinese financial power. For much of the past two decades, developing countries have treated the Chinese purse as if it were bottomless. But it has become clear that simply boasting the BRI brand has not led to much additional trade and investment compared to that which was already bound to take place anyway. The most competitive trade sources and investment destinations have continued to supply, or receive investment from, China, regardless of labels.

Brazil’s choice no longer seems so eccentric. Simply keeping away from the BRI has allowed Brazil – and other developing countries – to balance between China and the West without the burden of having to prove they are not a sell-off.