The Christmas Day raid on Cuxhafen in December 1914 is often considered to be history’s first seaborne airstrike when seaplanes from the British Royal Naval Air Service, launched from the seaplane tender (carrier) HMS Engadine, bombed a German zeppelin base.

Less well known is a ship-based air raid that took place a few months earlier that year in Tsingtao, China in September 1914 when a Japanese biplane launched from an aircraft carrier conducted a bombing raid on a warship of the Austro-Hungarian Navy. The attack occurred during the siege of Tsingtao (Quingdao), a port city in Shandong Province on China’s east coast, which in the late 19th century was leased to Germany by the imperial Chinese government as a colony.

This short engagement between an Austrian-Hungarian vessel and a Japanese seaplane may be history’s true first seaborne air attack.

At the outbreak of the First World War, Tsingtao was Germany’s major naval base in East Asia and home of the Imperial German Navy’s East Asia Squadron, the Kaiser’s only larger overseas naval formation independent of home ports in the German Reich. Commanded by Vice Admiral Reichsgraf von Spee, the squadron in the summer of 1914 consisted of six armored cruisers. However, at the outbreak of hostilities in Asia in August 1914 the ships of the squadron were dispersed all over the Pacific on routine missions, with only a token naval force left behind to defend Germany’s colony.

This token naval force at the end of August 1914 consisted of four gunboats, one torpedo boat and a warship of Germany’s ally Austria-Hungary, the Kaiser-Franz Joseph I-class protected cruiser Kaiserin Elisabeth of the Austro-Hungarian Navy. (Another German cruiser was being retrofitted in the port and not operational.) Originally, the German Navy wanted the warship to join its East Asia Squadron, but decided against it due to its low maximum cruising speed. Armed with two long-barreled 15 cm and six short-barreled 15 cm guns, the Kaiserin Elisabeth would constitute the bulk of Germany’s naval fire power in the upcoming siege of Tsingtao.

When war between the Entente and Central Powers broke out in Europe in August 1914, Imperial Japan, allied with Great Britain, saw a golden opportunity to seize German colonies in Asia. Tokyo especially set its eyes on Tsingtao as it was intent on expanding Japan’s influence in China. Consequently, in the middle of August it issued an ultimate to Germany to hand over Tsingtao to Japanese control. Germany refused. As a result, Japan dispatched an invasion force of 23,000 men supported by 142 guns and a fleet of Imperial Japanese warships to seize the port. Suspicious of Japanese actions, the British also dispatched a force of 1,500 to keep a watchful eye on the Japanese.

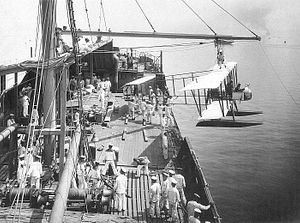

The invasion force landed on September 2 and commenced their assault on the city, while British and Japanese warships maintained a tight blockade on the port. (A German gunboat managed to sink a Japanese destroyer that day.) To fend off the British and Japanese invaders, the Germans could muster around 3,600 infantry and 324 Austro-Hungarian sailors. They were both outgunned and outnumbered. The Japanese naval force blockading the port included the seaplane carrier Wakamiya. Converted from a transport ship to a seaplane carrier, the Wakamiya was equipped with four Japanese-built French Maurice Farman MF.7 biplanes.

A seaplane from the Wakamiya went on a reconnaissance mission over Tsingtao on September 5 reporting to the allies that the German East Asia squadron had departed leaving only a minor naval force behind. As a result of the successful scouting mission, the Japanese decided to launch the world’s first sea-launched air raid the next day. A MF.7 biplane armed with hand-dropped bombs, took off from the Wakamiya on September and dropped its load on the Kaiserin Elisabeth and a German gunboat, without, however, hitting either vessel. Despite Austrian and German anti-aircraft fire (rifles and machine guns), the MF.7 was able to safely return from its sortie.

In the following days and weeks Japanese seaplanes were bombarding various other land targets. British officers serving during the battle of Tsingtao observed:

Daily reconnaissances, weather permitting, were made by the Japanese seaplanes, working from the seaplane mother ship. They continued to bring valuable information throughout the siege. The mother ship was fitted with a couple of derricks for hoisting them in and out. During these reconnaissances they were constantly fired at by the German guns mostly with shrapnel, but were never hit. The Japanese airmen usually carried bombs for dropping on the enemy positions.

The Wakayima hit a German mine on September 30, a few weeks into the siege, and had to undergo repairs for a week. The four seaplanes continued to bomb the German positions throughout the siege, as British officers noted in a dispatch:

The seaplane corps and three Henry Farman 100 h.p. seaplanes were, in consequence of the damage done to the mother ship, landed at the Base already established at Laoshan Harbor (to the West of the Bay so nearer to Tsingtao), and this proved eminently satisfactory.

One of the seaplanes was eventually shot down by the German’s sole functioning aircraft, believed to be the first documented downing of an aircraft during a battle. The pilot, Lieutenant Gunther Plüschow, claimed that he shot down the Japanese plane with his pistol, as his Taube aircraft was unarmed. In turn, Plüschow also conducted at least one air raid on the Japanese blockading fleet dropping two bombs. Both failed to hit their targets, however. (According to some accounts, he also attacked British and Japanese land forces.) Overall, the Japanese MF.7 launched 49 attacks and dropped 190 bombs during the duration of the battle.

The outcome of the siege of Tsingtao was never in doubt. Outnumbered six to one, the Germans withstood repeated assaults for over two months. Realizing that an outbreak was out of the question, the Germans scuttled their ships including the Austro-Hungarian cruiser Kaisern Elisabeth (although not before the ships heavy guns had been removed and installed ashore where they formed an artillery battery). Following a British-Japanese attack on November 6 that breached the German’s last defensive line, the German high command surrendered and the allies took possession of the colony on November 16.

A few weeks later, on December 8, German Navy’s East Asia Squadron would be destroyed by the British Royal Navy during the battle of the Falkland Islands. Overall, the British and Japanese suffered over 2,000 casualties, whereas the Austrians and Germans lost over 700 killed and wounded. The Austro-Hungarian and German prisoners were interned in Japan for the duration of the war and repatriated to Europe in 1920. While the military aircraft played no significant role in deciding the outcome of the siege, it nevertheless showed the potential damage aircraft could on surface warships.

A version of this article was published in The Diplomat Magazine.