From November 13 to 14, heads of state and government from Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa gathered in Brasilia for the 11th BRICS summit, a grouping of emerging national economies. China previously hosted the third and ninth BRICS summits respectively in Sanya and in Xiamen in 2011 and 2017. Amid China’s going global push, it has sought to foster linkages with the developing world, increasingly via regional groupings.

Earlier this fall, Beijing issued a new white paper outlining China’s relationship to the world. China’s view of itself as a developing country featured prominently. Most of its messaging was not new, drawing on win-win, South-South cooperation and assistance without conditions. Moreover, the paper emphasized China’s efforts to democratize the international system by advocating for and promoting the interests of other developing countries and highlighting the opportunities that the rise of China has brought by “fundamentally altering the international structures of power.”

China has also been a driving force behind further institutionalization of the BRICS. The group opened a development bank in 2014, headquartered in Shanghai with a regional office in Johannesburg. Each member contributed equally to the initial $50 million of capital. In its initial five years, the New Development Bank has issued loaned for almost 50 approved projects, funding primarily infrastructure projects. In August 2019, China opened its branch of the BRICS Institute of Future Networks in Shenzhen, designed to facilitate additional cooperation related to information and communication technology.

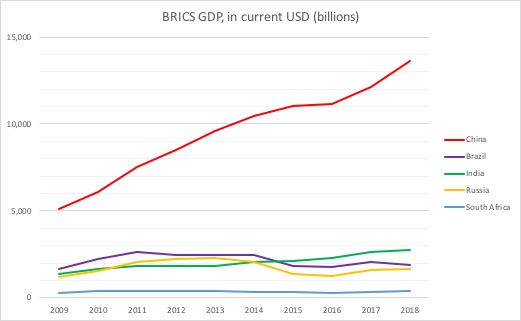

But excitement surrounding the BRICS may be waning. At the outset, the grouping brought together emerging national economies that appeared to show promising growth. Over the past 10 years, a few trends are clear. The sheer size of China’s economy sets it apart, while growth rates across the five members has been inconsistent and contracted.

Economic dynamics are not the sole factor dividing BRICS either. The grouping is subject to political divergences, not least stemming from domestic politics.

Ahead of the summit, Chinese President Xi Jinping met with Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro, their second meeting in less than a month. The China-Brazil relationship has been tested by the election of Bolsonaro who campaigned on taking a tougher stance against the expansion of Chinese influence in the South American nation. Bolsonaro not only railed against Beijing’s economic practices but also challenged the country on one of its most sensitive issues by visiting the island of Taiwan as a presidential candidate in February 2018. Since his election, however, the Brazilian president seems to have tempered his views. Last month in Beijing, Bolsonaro said that China and Brazil “were born to walk together.” Bolsonaro further echoed the complementarity of his country and China this week saying “China is becoming more and more part of Brazil’s future.” Non-binding agreements were made in investment, services, and transport industries. Brazil also invited China to participate in an auction for offshore oil drilling in Brazil. There has also been much debate over whether or not Brasilia will allow China’s Huawei to bid to develop Brazil’s 5G network.

Xi also met on the sidelines of the summit with his Russian and Indian counterparts. On Russia, Xi declared the bilateral relationship as solid and stable, based on friendship and mutual trust. He also called on China and Russia “promote solidarity and cooperation” within the BRICS bloc and signaled that the members are committed to multilateralism.

Meanwhile, the Chinese and Indian leaders both expressed an interest in developing closer communication channels, particularly on trade and investment issues. The latest meeting between Xi and Modi comes just days after India withdrew from negotiations of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a multilateral trade deal encompassing 15 countries in the Asia-Pacific region.

Professor Harsh V. Pant wrote in The Diplomat in 2016 that BRICS’s mandate was “under siege” amid slower economic growth and increasing intro-bloc political differences. Three years on, the observation holds. As the BRICS struggle to maintain relevance, Beijing is likely to recalibrate its approach to the bloc, not abandoning or withdrawing from it, but shifting its priorities and placing greater value in other regional multilateral groupings.