The current escalation in tensions between the United States and Iran presents a dilemma for China. While some analysts, such as on CNN, may portray the situation as an opportunity for China, in fact a closer look suggests that the situation is much more of a threat to China’s ambitions in the Middle East than not.

Several areas become proportionally more difficult for China with every step that worsens the already fraught relationship between the U.S. and Iran.

The first of China’s problems is its dependence on Middle Eastern oil, the access to which becomes proportionally more difficult and dangerous as Iran becomes increasingly isolated, and subject to sanctions.

Indeed, quietly, and almost certainly reluctantly, China has pulled away from buying Iranian oil.

As Forbes put it “China does not need Iran as much as it used to.”

As recently as July 2019, China was still importing a significant amount of oil from Iran, staring down U.S. over sanctions on purchases from Iran, and penalties on nations which defy those sanctions.

However, China has now turned to Saudi Arabia to supplement the oil that it increasingly shied away from purchasing from Iran during the last half of 2019.

“China has since turned to the Saudis, no longer able to trust Iran as a reliable source due to geopolitics,” Forbes reported.

Thus Iran, increasingly returning to pariah status in the United States, becomes a riskier partner for China in its Belt and Road Initiative investments, and as a key logistical stepping stone into the further reaches of the Middle East, and ultimately, Africa.

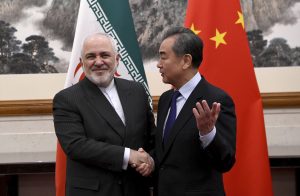

Then there is China’s criticism of the United States’ action to take out Iranian Quds force leader Soleimani. The statement from China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs detailing Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s call with Iranian Foreign Minister Zarif on January 4 is notable, but primarily for its internal inconsistencies:

“Wang Yi said that the military adventurist act by the US goes against basic norms governing international relations and will aggravate tensions and turbulence in the region. China opposes the use of force in international relations. Military means will lead nowhere. Maximum pressure won’t work either. China urges the US to seek resolutions through dialogue instead of abusing force. China will continue to uphold an objective and just position and play a constructive role in safeguarding peace and security in the Gulf region of the Middle East.”

The “objective and just position” which China claims it will uphold is belied by defining the U.S. action to kill Soleimani as a “military adventurist act.” By defining the act as “against basic norms of international relations,” China leaves no doubt as to which camp it stands within, and of where it feels its most important interests lie.

For the moment, this is not surprising. China has made huge investment commitments in Iran, through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). As we reported in July 2018, “both Iran’s superior geographic position as a logistical access point along BRI trade routes, as well as its political reliability from a Chinese perspective in light of its hostile relationship with the United States, make Iran indispensable to China’s BRI calculations.”

But are the financial, logistical, and strategic advantages of a deepening relationship with Iran more important to China than its troubled but still tremendously large trade relationship with the United States, not to mention American investment in China itself?

Indeed, as China tries every arrow in its quiver to gain access to Western technologies which it intends to not only master but to mimic and monopolize, it could be easy to bet on its relationship with the United States and Europe topping the charts of its calculated interests.

But since mid-2018, China’s gamble in Iran has taken on new proportions.

At the end of August 2019, Zarif went to China to meet Wang Yi.

The public details of what came out of that meeting show that the bilateral relationship between the two nations has gone to a whole new plateau, one that Petroleum Economist calls “a potentially material shift to the global balance of the oil and gas sector.”

The terms, which are an update to the China-Iran comprehensive strategic partnership of 2016, are reported to be in two parts. The core plank is that “China will invest $280 billion U.S. dollars developing Iran’s oil, gas and petrochemicals sectors.”

Then China will invest a further $120 billion into Iran’s transport and manufacturing infrastructure.

And, as Ariel Cohen writes in Forbes, “sanctions be damned.”

Meanwhile, China, “which opposes the use of force in international relations,” has not hesitated to fortify the South China Sea with man-made islands fitted out with military installations, despite a binding Hague verdict denying China its claims in the disputed region.

And then there is the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), commonly known as the Iran nuclear deal.

Iran has said it is pulling out of the deal now. China says it will rush to the rescue and spare no effort to save it.

But China, which on the face of it attempts to be associate of all, but friend to few, may find that its stated non-interventionist, non-interference approach to diplomacy gives it limited leverage diplomatically. The policy is welcomed by some nations, particularly those which, like China, do not care to have a bright light put on issues such as religious and political rights.

Other nations, however, may see this policy track as indecisive, opportunist, and even weak, leaving China with little capital of principle from which to negotiate, especially when its interests, particularly in Iran, are so diametrically opposed to those of Western nations which it would also like to gain from.

China’s dilemma is clear. Having made no real commitment to either nation, or to any fundamental principles which could tie it to either, other than those economic interests which are in its own self-interest, may find that its role as an “honest broker” is toothless, and its efforts hollow.