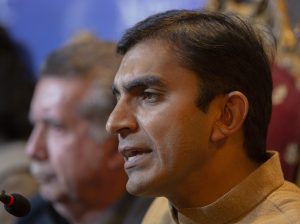

Pakistani authorities arrested the 28-year-old leader of the Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement (PTM, or the Movement for the Security of Pashtuns), Manzoor Pashteen, on Monday as part of their effort to clamp down on dissent. The Pakistani military has repeatedly accused the PTM of fomenting chaos along Pakistan’s border with Afghanistan by demanding civil rights and accountability for the actions of troops ostensibly fighting terrorists in that region.

Instead of silencing the opposition, Pashteen’s arrest has unleashed a storm of criticism both instead and outside the country against Pakistan’s authoritarian drift. Authorities also arrested Mohsin Dawar, member of parliament from Waziristan, who had been released on bail last September after spending four months in prison.

There is no sign that the arrests will end the nonviolent PTM campaign, which has become the strongest challenge to the military’s political control of Pakistan after the mainstream opposition decided to acquiesce to military supremacy. If anything, Pashteen has now become a symbol of resistance to military dominance and the PTM is finding support outside its traditional base.

Pashteen’s arrest was quickly condemned by international human rights organizations as well as Afghan President Ashraf Ghani and his predecessor Hamid Karzai. Pakistan’s government reacted sharply to the Afghan statements, describing them as interference in Pakistan’s internal matters. Given the fact that ethnic Pashtuns straddle the Afghanistan-Pakistan border, Pakistani officials are always sensitive to Afghans taking in interest in the lives of Pakistan’s Pashtuns, fearing irredentist or separatist demands.

The Pakistani establishment has always been fearful of ethnic politics, which challenges the establishment’s narrative of a religion-based Pakistani nationalism. But Pakistan’s ethnicities predate the idea of Pakistan and state brutality has not been enough to erase them. Although brutal suppression did not prevent erstwhile East Pakistan from becoming Bangladesh in 1971, the Pakistani military has yet to figure out how to run Pakistan as a multiethnic federation.

The PTM has been careful not to question the idea of Pakistan while demanding that Pashtuns in Pakistan’s tribal areas be accorded all protections and rights enunciated in Pakistan’s constitution. The movement was born in reaction to years of war and destruction. It blames Pakistani authorities for supporting the Taliban, insists that such support be shut down, and calls for the end of military oppression in the areas where Pakistan says it is acting against terrorists and jihadis.

The PTM started out as a social movement around 2014 to raise awareness for the need to remove landmines in the tribal areas, which served as the staging area for the Mujahideen fighting the Soviets in Afghanistan during the 1980s. The territory was also the stomping ground of the Afghan Taliban, backed by Pakistan’s military, and the various anti-Pakistan local militant factions that sprouted in the aftermath of 9/11.

The PTM started protests against enforced disappearances and government-backed violence at the beginning of 2018. Pashteen cast himself as heir to the nonviolent tradition of leaders like Martin Luther King and Abdul Ghaffar Khan (Bacha Khan), known popularly as the Frontier Gandhi. He tapped into the legacy among Pashtuns of Bacha Khan, whose Khudai Khidmatgars (Servants of God) had confronted the British from 1929 to 1947 and subsequently confronted Pakistan’s undemocratic regimes.

As a movement, the PTM is organic, young, and consists of people who have seen the loss of so much life among their own that they know there is no room to abandon or soften the stand they have taken. It represents Pakistan’s young demographic profile. Pashteen is only 28 years old while the movement’s two members of the National Assembly are in their early 30s. Gulalai Ismail, a child rights activist also in her 30s, is the movement’s leading female face.

The PTM got a boost from sentiment among Pashtuns that they have suffered due to Pakistan’s erroneous policy, first of supporting the Taliban and then trying to control the border with Afghanistan through military air campaigns and ground operations. Hundreds of Pashtun civilians have been killed in the multiple wars beginning in 1979. The PTM has wrestled with the government over the fate of the disappeared and has sought “justice for their people in all areas.”

The PTM has continued to grow even though its activities, including rallies attended by tens of thousands, have been completely blocked on Pakistan’s media. Youthful PTM members have harnessed the power of social media in Pakistan to share videos of their activities, which now resonate far away from Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa province. PTM has inspired civil and political groups fighting for their rights all over the country.

Pakistan’s military-led establishment has, over the years, mastered the art of dealing with dynastic mainstream political parties. The generals alternately allow these parties into government to share the fruit of patronage and accuse them of corruption, using the charges as leverage for subsequent deals on policy matters. But the PTM is a movement to be reckoned with because its leaders seem focused on issues and not self-aggrandizement.

Even after Pashteen’s arrest, it is unlikely that the PTM will weaken or wither away. Pakistan’s all-powerful military could keep Pakistan’s integrity as a state by allowing the people to voice their pain and complaints. But instead it has persisted with its old tactics in calling Pashteen a traitor. If it insists on killing, jailing, torturing, or exiling him, as has been the fate of past Pakistani dissidents, the PTM might offer a different response.

Like the nonviolent civil rights movements that it seeks to emulate, the PTM will likely weaken the status quo through attrition. The very fact that the authorities of a nuclear-weapons power cannot bear criticism from a 28-year-old, delivered at rallies in a relatively remote border region of Pakistan, points to the strength and power of Manzoor Pashteen and his PTM.

Farahnaz Ispahani is a Senior Fellow at the Religious Freedom Institute and a Global Fellow at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, DC. She is a former Member of the Pakistan Parliament and author of Purifying the Land of the Pure: Pakistan’s Religious Minorities.