As Iran continues to dominate headlines across the Western world, China’s far quieter quest to influence Africa and Asia has escaped the news media’s attention of late. The many examples of this Chinese strategy include the world power’s relationship with Eritrea, a country on the Horn of Africa that rarely features in geopolitical discussions. Nonetheless, officials in Beijing intend to turn what some analysts still label “Africa’s North Korea” into a centerpiece of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China’s costly economic megaproject inspired by the Silk Road.

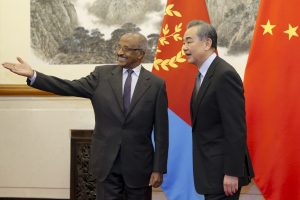

In May 2019, Eritrean Foreign Minister Osman Saleh Mohammed and Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi met in Beijing to laud what Eritrean officials dubbed “a healthy and strong partnership for the benefit of their two peoples.” Just five months later, Chinese Ambassador to Eritrea Yang Zigang said in an interview with Eritrea’s state-owned media that “China has consistently supported Eritrea’s nation-building endeavors by providing Eritrea with many kinds of assistance.”

The months of diplomatic niceties between China and Eritrea preceded a much more substantive development barely noticed by Western news agencies. In early November, the China Shanghai Corporation for Foreign Economic and Technological Cooperation — known as “China SFECO Group” — began building a 134-kilometer road in coordination with ranking Eritrean officials, an initiative heralded by Yang. He has displayed a keen interest in Eritrean infrastructure, noting on the embassy webpage, “Eritrea is endowed with two great natural harbors, Massawa and Assab.”

Eritrea has long expressed its enthusiasm for the Belt and Road Initiative, China’s bid to expand its sphere of influence by investing in countries across the Global South. A representative from Eritrea’s ruling party traveled to Beijing’s Belt and Road Forum in 2017. The Eritrean Information Ministry, meanwhile, praised China’s effort in 2019, calling it a step toward “open, inclusive, and balanced regional economic cooperation” and “integration of markets.”

At first glance, a little-known one-party state with an ailing economy would seem an odd choice for Chinese investment. Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki has only succeeded at turning his country into a pariah state during 27 years of brutal rule, and the World Bank Group considers Eritrea “one of the least developed countries in the world.” Even so, Chinese President Xi Jinping likely sees his investment in Afwerki’s regime as an opportunity to secure an ally on the Red Sea.

Chinese tacticians have been eyeing the strategic region for some time. In early 2016, China concluded a deal with Djibouti, one of Eritrea’s neighbors on the Red Sea, to construct a military base – China’s first overseas military facility. The much-discussed Chinese outpost, which itself borders a similar American facility, became operational a year later. China has deployed soldiers throughout East Africa, even sending peacekeepers to secure Chinese-staffed oil wells in South Sudan.

Chinese-Eritrean relations appear focused on economics for the time being, but the possibility of militarization looms on the horizon. China and Eritrea cooperate in a variety of sectors, including energy and public health. The East Asian world power has a long history with its East African partner, arming Eritrea not only during its 30-year war of independence from Ethiopia but also during its second war with Ethiopia in the late 1990s. In more recent years, China has offered to mediate territorial disputes between Eritrea and Ethiopia, a sign of China’s wider ambitions.

In Africa and Eritrea in particular, China’s distinct foreign policy has given it a critical advantage over its Western rivals. Xi is more than willing to ignore Afwerki’s well-known abuses of human rights, such as conscripting tens of thousands of Eritreans and forcing them into what the United Nations terms “slave-like” labor. Though Eritrea has a population of just 6 million, only Syrian applicants for asylum outnumber Eritreans in Europe. Fifty thousand live in Germany alone.

While some Western countries have tried to engage with Eritrea in the last few years, they have faced backlash. European officials suffered significant embarrassment when The New York Times revealed that an Eritrean project funded by the European Union and facilitated by the UN relied on the labor of conscripts. Many European countries view Eritrea as a source of mass migration and a key front in their bid to stop it. Unlike China, which Afwerki has tried to court through his emphasis on Eritrea’s “strategic location,” Europe seems to have few long-term goals there.

The United States, China’s main rival in Africa, has indicated little interest in Eritrea. The State Department has admitted that “[t]ensions related to the ongoing government detention of political dissidents and others, the closure of the independent press, limits on civil liberties, and reports of human rights abuses contributed to decades of strained U.S.–Eritrean relations.”

As long as China keeps overlooking Eritrea’s dismal record on human rights, the two countries’ relationship seems likely to blossom. Despite a remarkable increase in goodwill toward the East African autocracy following Eritrea’s conclusion of a peace treaty with its longtime adversaries in Ethiopia, Afwerki has few friends in the international community. For its part, China has long stated its reluctance to interfere with or even comment on other countries’ internal affairs. That position has endeared Beijing to autocrats around the world.

For now, China only has one opponent in the race to establish a sphere of influence in Eritrea: the United Arab Emirates. The UAE operates an air base and a military port in the East African country in addition to its military base in Somalia. In a sign of China’s growing reach, however, the UAE is participating in the Belt and Road Initiative. Considering that China’s ambassador to the Middle Eastern regional power vaunted their relationship as “at its best period in history” in 2019, the prospect of a confrontation between the two countries over Eritrea seems dim.

SFECO Group’s project in Eritrea marks a new level of cooperation with China. As American and European officials turn their attention to the Middle East, China’s staying power in the Horn of Africa is growing. The Chinese presence in Djibouti sparked alarm across the West. In Eritrea, though, China is reaping the benefits of other world powers’ lack of interest in a rogue state. Unlike its Western counterparts, China has its sights set on the Red Sea.

Austin Bodetti studies the intersection of Islam, culture, and politics in Africa and Asia. He has conducted fieldwork in Bosnia, Indonesia, Iraq, Myanmar, Nicaragua, Oman, South Sudan, Thailand, and Uganda. His writing has appeared in The Daily Beast, USA Today, Vox, and Wired.