Editor’s Note: The following is a preview of the latest edition of the APAC Risk Newsletter, presented by Diplomat Risk Intelligence. To read the full newsletter, click here to subscribe for free.

“This is not a drill. … This is a time for pulling out all the stops.” – WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, March 5, 2020.

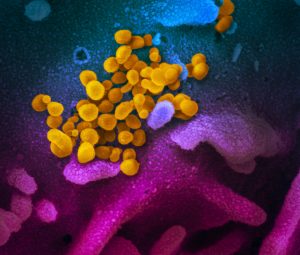

This issue of the newsletter will be a little different than previous ones. I want to take some time to talk about the global spread of COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus known as SARS-nCoV-2. I should start by stating that no one really knows exactly how bad things are going to get; given this, the answer is not to give in to widespread panic, but to think carefully about managing risk under conditions of uncertainty.

Anyone exposed to Asia—and also U.S. equity markets—may be asking about what exactly is driving both a) a significant downward correction that may be pointing toward a recession, and b) sharp volatility. The last time this newsletter addressed SARS-nCoV-2, it was still being treated as a localized epidemic in China; the “COVID-19” coinage hadn’t arrived and even more remained unknown. A consequence of how the virus was covered initially was that global investors mainly anticipated supply-side shocks in China. This was far from insignificant; despite trade war manufacturing hedging, China remains the world’s factory by and large. As a small bit of respite, the initial outbreak preceded the Lunar New Year Holiday, a time of depressed factory productivity anyway. It appeared that the market saw the added burdens of COVID-19—even with the dramatic shutdowns affecting Hubei province—as an adverse event that could largely be weathered by the world’s largest China-exposed companies.

But it quickly became clear that COVID-19 was trending toward the worse end of possible scenarios. Even as the WHO remains cautious about declaring the disease a pandemic, it is looking increasingly like the disease may have the potential to become the sort of once-in-a-100-years public health shock that sinks unprepared businesses. Billionaire philanthropist Bill Gates, writing in the New England Journal of Medicine, noted that “Covid-19 has started behaving a lot like the once-in-a-century pathogen we’ve been worried about.” He counsels that evenwithout knowing the full extent of the virus’ ability to cause real damage to human life and health—questions persist about its CFR, or case fatality rate—governments and businesses should be treating it like an epochal event.

Beginning in the final week of February, this appeared to sink in across the world. In economic terms, it became clear that COVID-19 wasn’t just going to be a contained supply shock, limited to China, but that it was going to be an unrestricted shock to interlinked global supply chains and an even less restricted shock to global demand. As the virus arrived quickly and with devastating consequences to European and American shores and panic set in worldside, it became clear that the fundamental human behaviors that underpin all “normal” economic demand would be upended. That’s why the U.S. stock market quickly shed more than 12 percent of its nominal value by the end of February and why a recovery appears to be a distant prospect at the moment.

In the midst of all this, it looks like monetary policy is not an answer to assuaging investor concerns because, fundamentally, the price of money is not the issue. The U.S. Federal Reserve’s surprise rate cut of 50 basis points—the first since the financial apocalypse of 2008—thus had little to no effect on confidence, but instead took the U.S. closer to a negative interest rate policy, leaving the Fed with little room to maneuver if and when the COVID-19 panic stabilizes. In many ways, the Fed’s move appears to have signaled to investors that the U.S. Central Bank—whose mandate, incidentally, is not concerned with the nominal value of stock indices, but with unemployment and inflation—expects COVID-19 to cut at the fundamentals of the U.S. economy. The Federal Open Market Committee observed—in a somewhat tone-deaf manner—that even as the “fundamentals of the U.S. economy remain strong … the coronavirus poses evolving risks to economic activity.” Clearly, the scale of coronavirus panic has affected the most fundamental element of the U.S.—and global—economy: human confidence and demand.

That much appears to be apparent to the Bank of Japan’s governor, Haruhiko Kuroda, who took a decidedly bleak tone this week. Tokyo’s been facing off with SARS-nCoV-2 for a little longer than the United States—at least directly—and Kuroda says he expects serious damage to the Japanese economy as a result. “If the epidemic is prolonged, it could also affect production,” he said. “We need to be mindful that the impact from the outbreak could be big.”

* * *

I’ve been in Taiwan this week, watching the spread of global panic. What’s been interesting in meetings here with business leaders is their thinking about what the Asian economic landscape might come to look like after the COVID-19 dust settles. One of the observations that I found most interesting was that many Taiwan-based manufacturers and suppliers of high-end components in the technical sector see COVID-19 as potentially accelerating a regional readjustment away from mainland China exposure more broadly. One supply chain analyst I spoke to observed that many Taiwan-based suppliers had, under the Tsai Ing-wen government’s New Southbound Policy encouragement and organic concerns about the U.S.-China trade war, started to already look away from the mainland. While COVID-19 is causing a massive bloodletting in Taiwan as it is everyone else, there’s a sense of optimism that this shock could spur a greater diversification of Asian supply chains. In a sense, the post-COVID-19 winners could be low-cost, high-value manufacturers in Southeast Asia and South Asia.

Given my epistemic hedging at the onset of this newsletter, it’s probably best not to think too hard about what the post-COVID-19 world looks like, but there’s a strong sense—at least here in Taipei—that it’ll be a shock to much of what we’ve come to know about how the Asia-Pacific does business and supply chains.

In the shorter term, the question for many businesses in Asia—particularly small and medium enterprises—is survival. Consumer businesses are hard hit and many may find themselves unable to service existing debt if depressed demand persists. In Taipei, for instance, many of the city’s most popular tourist attractions and shopping areas have been largely depopulated—and this is in Taiwan, one of the places that’s been doing an excellent job generally containing COVID-19.

* * *

In the coming days and weeks, your top priority should be doing all you can to protect those most vulnerable to the effects of COVID-19: the elderly and immunocompromised. This mostly boils down to washing your hands effectively. Here in Asia, there’s massive social pressure to wear face masks and, even as masks are only useful once one is already sick, these are virtually everywhere. In the United States, the surgeon-general has expressed concern that panicked mask-buying could spur harmful shortages for healthcare workers, who need face masks to protect themselves.

To read the entirety of the latest edition of the APAC Risk Newsletter, presented by Diplomat Risk Intelligence, click here to read and subscribe for free.