South Korean elections are often a wild and unpredictable adventure. That said, this year’s National Assembly election will be one for the books — less so for the polling result than for it being held at all. Other nations have postponed elections due to the COVID-19 pandemic or held them amidst controversy. While South Korea’s COVID-19 testing program is cited as the global gold standard for epidemic response, it is uncertain whether its election procedures will be similarly lauded.

Contests for all 300 seats of the unicameral National Assembly will come to a vote on April 15. President Moon Jae-in’s term does not expire until 2022, but legislative elections are interpreted as a public referendum on the president’s tenure.

Initially, the COVID-19 outbreak had created uncertainty over whether the elections would be held as scheduled. But South Korea’s expansive testing and monitoring program overcame the worst of the epidemic. Moreover, the nation has experience holding elections during major calamities. Duyeon Kim, senior advisor for Northeast Asia at the International Crisis Group, highlighted, “Elections have never been postponed in Korean history, not even during the Korean War or the H1N1 outbreak.”

This year, the National Election Commission (NEC) has articulated strict health protocols requiring voters to wear face masks and disposable gloves, maintain social distancing, and pass a temperature check before casting a ballot. Voters failing the temperature check will be required to use a special voting station that will then be disinfected. People in quarantine will be allowed to vote by mail from home.

However, the system is not without its problems. Most notably, it precludes half of the 170,000 Koreans living overseas from voting. Citizens abroad cannot vote by mail, but may cast a ballot at South Korean embassies or consulates overseas. But this year the NEC has stopped election-related operations at 86 diplomatic missions in 51 countries due to the pandemic.

In an email interview John Delury, a professor at Yonsei University in Seoul, commented: “The three issues that might have been a focal point under normal circumstances — growing the economy, addressing social ills, and managing North Korea — have receded into the background or taken radically new shape. Instead the central, existential issue right now is surviving COVID-19.” As a result, Delury believes the election is likely to “serve as a referendum on the sitting government’s COVID response efforts.”

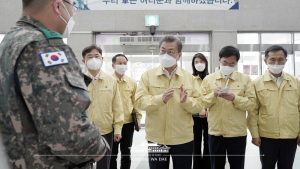

This has played to Moon’s advantage since, after some initial criticism, he is generally perceived as overseeing an effective government response, which enabled South Korea to flatten the curve of new cases.

Moon is gaining recognition from global leaders. World Health Organization Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus praised Moon’s leadership and requested he deliver a keynote speech to the organization’s teleconference. At least 15 foreign leaders have called Moon seeking his quarantine advice or South Korean test kits.

As a result, approval ratings for Moon and his party have surged from 41 percent and 34 percent respectively in January to 56 percent and 41 percent in April. Nearly 60 percent of survey respondents approved of Moon’s response to the pandemic. Meanwhile support for the main conservative opposition United Future Party increased slightly, to 33 percent. The opposition has struggled to coalesce since the impeachment of then President Park Geun-hye.

While support for Moon and his party has improved, it hinges on the success of the government’s COVID-19 response and the failure of the opposition parties. Delury observes that “the major liberal and conservative parties seem to remain generally unpopular. The onus was on the opposition to generate some new, dynamic, unified leadership that could tap public sentiment, and they appear to have failed.”

Election predictions earlier this year suggested Moon’s party could lose a large number of legislative seats. Currently, the ruling Democratic Party has 120 seats (41 percent) to the main opposition United Future Party’s 92 seats (31 percent). Moon’s party is now expected to do better, perhaps retaining or even gaining seats. Lee Hae-chan, chairman of the Democratic Party, said the party expected to win 130 seats.

But it remains unclear to what degree voters will focus solely on the government’s COVID-19 response or return to previous concerns about important economic and domestic issues. A new election law, designed to increase representation of small parties, adds another layer of unpredictability. Both the ruling and major opposition parties have set up smaller satellite parties to gain more additional proportional representative seats. A record high of 35 parties will compete in the upcoming election.

The election results will set the tone of South Korea’s domestic and foreign policies for the next two years. Kim of International Crisis Group commented, “While South Koreans will base their votes on domestic issues or party loyalty, the results of the elections will still impact foreign and inter-Korean policies going forward.” If Moon’s party does well, it will reinforce his ability to continue his administration’s policies and improve the potential to pass the baton to another progressive president in two years.

The administration, though stymied by Pyongyang’s rejection of all dialogue with the South, would maintain its eagerness to engage with North Korea. Moon will also press for expedited return from the United Nations Command of wartime operational control of South Korea’s military forces. Although Seoul has implemented significant improvement to its military forces, it has not yet attained sufficient ability to conduct joint and combined-arms operations in modern, multidomain wartime conditions requisite to assuming wartime operational control.

A strong ruling party result would affirm Seoul’s resistance to Washington’s demand for a mammoth increase in military cost-sharing. While South Korean support for the U.S. alliance remains strong, there is no support, even among conservatives, to acquiesce to President Donald Trump’s funding demand.

Conversely, a strong showing by the conservative opposition would impede Moon’s efforts to institute progressive electoral reforms and could turn the president into a lame duck earlier in his tenure.

Regardless of the election outcome, the world will be watching South Korea’s ability to fairly and effectively hold a nation-wide election while most other countries remain in lockdown. A well-run election that safeguards constitutional principles while protecting public safety would again lead nations to seek to emulate South Korea.

Bruce Klingner is Senior Research Fellow for Northeast Asia at the Heritage Foundation. He previously served 20 years with the CIA and Defense Intelligence Agency, including as CIA’s Deputy Division Chief for Korea.