In the less than three decades since the collapse of the Soviet Union, China has emerged as a key player throughout Central Asia. Yet, despite increasingly prominent political, economic, and security relations, China for most Central Asians remains a little known, poorly understood, and even feared country. Since the 2000s, articles critical of Beijing’s policies have proliferated in Central Asian media. Over the past three years, several demonstrations have been organized in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan to challenge the Chinese “soft expansion” in the region. Aware of the potentially negative impact of increasing Sinophobia on its foreign policy, China has countered with public diplomacy and soft power policies, including in Central Asia.

However, is Beijing succeeding, or will it succeed, in reversing this trend in the region? And could Sinophobia jeopardize China’s presence and relationships?

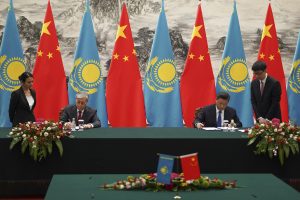

Soon after independence, Beijing started developing strong diplomatic relations with all the governments in the region. China’s good neighbor policy quickly materialized into significant economic relationships. With between $26 and $45 billion in annual trade, China has been for more than 15 years the first or second trading partner of every state in Central Asia, now far ahead of Russia, which had largely dominated until 2008. Beijing has become the main investor in several key sectors such as oil, gas, mineral ore extraction, infrastructure, and banking, and has gained increasing visibility with the multitude of consumer goods it exports to the region.

In 2013, China’s ambitions in the region were significantly substantiated with President Xi Jinping’s announcement of hundreds of billions of dollars of investment in what would come to be known as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to connect, by trade and infrastructure, Asia with Europe and other continents along ancient trade routes. In addition, the Chinese and Central Asian governments have developed a common narrative on regional security and signed a set of cooperation agreements to address nontraditional threats such as violent extremism.

Despite its success in emerging as a global power, China’s development model, which combines state capitalism and an export-oriented economy with authoritarian one-party constitutionalism, remains unpopular compared to other models, in particular the Russian one, which between one-half and three-quarters of Central Asian youth view as a benchmark. These concerns are further fed by clichés and phobias inherited from the Soviet regime, which after the Sino-Soviet rupture had portrayed China as an enemy of Islam and of all Turkic peoples.

Such apprehensions about China are not specific to Central Asia. From Asia to Africa and Latin America, Beijing’s ambition to become the world’s leading power and its fast-growing presence abroad have triggered debates, resistance, and even Sinophobic sentiments.