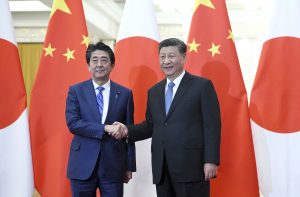

On March 5, the Japanese government announced that Chinese President Xi Jinping’s much-anticipated visit to Japan would be postponed. Given the worsening pandemic, the news was hardly surprising. The next day, the government announced tightened travel restrictions from China. That prompted criticism, from those observers who saw the timing as suggesting that Prime Minister Shinzo Abe had held off on the travel restrictions out of consideration for Xi’s visit.

However, something else was happening on March 5. At 5:15 p.m., Abe made the following statement at the 36th Council on Investments for the Future at the Prime Minister’s Office. “There are some concerns over the impacts of the decline in product supply from China to Japan on our supply chains. In light of that, as for those products with high added value and for which we are highly dependent on a single country, we intend to relocate the production bases to Japan. Regarding products that do not fall into this category, we aim to avoid relying on a single country and diversify production bases across a number of countries, including those of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).” This was Abe himself announcing a policy based on concerns about the risk of Japan’s supply chains being excessively dependent on China.

The policy took shape in the 16.8 trillion yen revised budget proposal presented on April 7. It included 248.6 billion yen as a measure to reform Japan’s fragile supply chains. Building on this, the aim is to provide new subsidies to encourage Japanese manufacturers to bring production centers back to Japan and diversify into other Asian countries. China clearly understood that Abe was pushing for a decoupling, with protests from the Chinese government. Chinese media has meanwhile claimed that it will not be easy for Japanese companies to withdraw and would not at any rate be to their benefit.

Most Japanese companies will have understood the risks inherent in the Chinese government’s actions during the coronavirus pandemic, specifically the lack of guarantees for the rights of companies or their workers. Moreover, Japan–China relations happened to be good, so the Japanese government was able to send a chartered aircraft to Wuhan to bring back Japanese nationals. But if relations had not been good, it is most likely that many Japanese company workers would have had no choice but to remain in the beleaguered Chinese city. It is likely that quite a few companies have been making preparations to reduce their risk exposure. In this regard, Abe’s statement can be said to reflect this Japanese corporate thinking.

However, the government’s policy is to relocate production bases to Japan and to avoid relying on a single country by diversifying the locations of production facilities. Not all Japanese companies are getting ready to withdraw from China. This is not about severing supply chains between Japan and China; rather, it is a matter of production bases. Related strategies like “China plus one” were already being advocated back during the period of anti-Japanese demonstrations in China.

In particular, the shift to domestic production and diversification of China-reliant products are hardly new phenomena, and indeed have already taken place to a certain extent. In this sense, it is not so much that the Japanese government has suddenly started instigating a decoupling, but rather that the government is simply saying that it will provide support to Japanese companies in China if they wished to come back to Japan in light of the pandemic, with some conditions attached.

In other words, supply chains between Japan and China will remain intact, the Chinese market is still important, and Japan is not encouraging a decoupling from China.

Nevertheless, the policy measure included in Abe’s statement and the revised budget is significant. Some U.S. observers have voiced approval for the measure, and China has clearly taken note. If the Japanese government does not provide clarity about the intentions of its policy, it risks adding fuel to the growing tensions between the U.S. and China.

Shin Kawashima is a professor at the University of Tokyo.