It has been more than three years since Cambodian opposition leader Kem Sokha was arrested for treason, after the country’s government spuriously claimed that he was plotting of a U.S.-backed coup with his now-banned Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP). His trial, once again postponed because of the COVID-19 pandemic, may not take place until 2021. But changes are afoot.

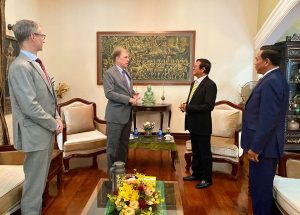

This week, Kem Sokha was allowed to meet with the U.S. Ambassador to Cambodia, W. Patrick Murphy, and reportedly discussed the country’s human rights situation, even though his bail conditions forbid him from “engaging” in politics. This meeting came shortly after Prime Minister Hun Sen expressly ordered the authorities to let Kem Sokha join in the relief efforts for those affected by Cambodia’s recent deadly flooding. At first, it appeared that Cambodian officials were wary of letting Sokha donate money and visit flood-affected areas, ostensibly because they didn’t want to be seen as favorably treating someone accused of treason. More likely, they didn’t want to be seen as coddling the leader of a banned opposition party. Amid the pandemic and the floods, the government’s thugs have continued their violent reprisals on opposition supporters, as witnessed by a brutal beating and more arrests just this week. However, Hun Sen intervened and ordered his officials to allow Kem Sokha to donate money, hand out food and meet with ordinary people. In recent weeks, he has also been allowed to travel across Cambodia more freely.

What explains these developments? Perhaps Hun Sen is growing soft with senescence, though probably not. As always, one must ask how all of this benefits the prime minister. As I’ve argued before, the treason charge against Kem Sokha created problems for the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP). For starters, the charge lacks any substantial evidence, so the CPP is wary of the fallout that might ensue when the trial actually takes place. The decision to charge Kem Sokha with treason was a risky choice, given that it could so easily have chosen a less severe crime to pin on him. No doubt, it was a decision made in haste.

A moment’s thought will suffice to show that Sokha was arrested and the CNRP forcibly dissolved in late 2017 because Hun Sen was anxious. In the summer of 2017, the CNRP secured a significant result at the local elections, picking up 43 percent of the popular vote, 489 commune chief positions out of a possible 1,646, and 5,007 commune councilor posts out of 11,572, thereby ending the ruling CPP’s near-monopoly on locally-elected posts. At the previous local election in 2012, the CPP won 1,592 of the 1,633 commune chief posts. In 2017, it lost 436. So not only did the CNRP roughly maintain its share of the popular vote from the 2013 general election; the result also gave it momentum heading toward the 2018 general election, since it now had far greater reach at the village level, thanks to its new chiefs and councilors.

The CPP realized this and moved quickly, just three months after the local election, to end the threat. But the treason charge meant it was always going to be difficult for Hun Sen to walk back his attacks on Sokha once it became politically convenient to do so. It was one thing to pardon Sokha in December 2016 for not turning up at court for hearings into a politically-charged case involving NGOs and an alleged mistress. It was quite another to pardon and try to turn him into a puppet for a foreign-backed coup plot. Either the government was lying all along about the treason (the correct conclusion) or Hun Sen was going soft on someone allegedly planning the illegal overthrow of his government.

Many observers have predicted that Kem Sokha will eventually be convicted of treason but then swiftly handed a royal pardon by Hun Sen, on the express understanding that Kem Sokha disengages from politics. This still appears a likely scenario – but perhaps not the ideal one for the Cambodian leader.

There are many reasons to doubt whether the ruling CPP can continue with its de facto one-party rule indefinitely. Its assault on Cambodian democracy created (and will continue to create) considerable problems for the government because of Western unease, including the EU’s partial removal of Cambodia’s trade privileges in August, which will hit the economy hard. It has also removed one of central element of the party’s narrative. Hun Sen’s rule depends on creating a permanent sense of peril. Since the 1990s, he has tried to sow maximum fear amongst the public by constantly telling them that Cambodia could very easily descend back into anarchy and brutality of the Khmer Rouge days if the CPP were to fall from power. In that event, Cambodia would “fall into mud” like in the 1970s, Interior Minister Sar Kheng stated last year.

In order to appear indispensable to Cambodia’s peace and prosperity, Hun Sen must show at least the possibility that he could be forced from office, not only to rally his supporters, but also the rally his disparate party behind his leadership. Indeed, Hun Sen needs a threat, a challenger, an opposition party – not a particularly successful one, but at least one that he can portray as endangering the CPP’s hard-won achievements. Without an identifiable opponent or enemy, however, the CPP’s propaganda rings hollow. By removing any identifiable threat to the peace, the ruling party also removed the specter of the chaos that is so central to its legitimating myths.

And without the imagined threat of a “color revolution,” the government’s repressive tactics are becoming increasingly obvious for what they are. We are left with a situation in which the CPP’s cheerleaders have to find an existential threat in the most basest forms, as best characterized by the headline of a recent op-ed in the Khmer Times: “Chinese military base speculation hurts Cambodian people.” (As if reporting by independent journalists could harm the Cambodian public.)

It is possible that Hun Sen would prefer if Kem Sokha returned to politics – but greatly weakened, divided from the rest of the CNRP movement and knowingly in the prime minister’s pocket – than for him to bow out entirely and risk a new opposition leader rising to the fore. Indeed, Hun Sen this month again dared the exiled CNRP grandees to return to Cambodia to face trial next month, something that he has in the past actively prevented and won’t allow this time, but which he knows will open up further divisions within opposition circles.

From what I hear, Sokha didn’t exactly play ball after he met with Hun Sen in May, at the funeral of the prime minister’s mother-in-law. Possibly, then, Hun Sen’s missives this month are another attempt to win him over – and to ease the public into not batting an eyelid when the verdict of Sokha’s trial is eventually read out. This may also explain why the authorities now appear more eager than ever to arrest and harass former CNRP officials and members. Once it has been entirely defanged and stripped bare, Sokha could be allowed to return as leader of a rump CNRP, a party that is no more than a carcass of its former self.