If you need a number to tell you how angry the world is at Xi Jinping’s China, I have one: 85.

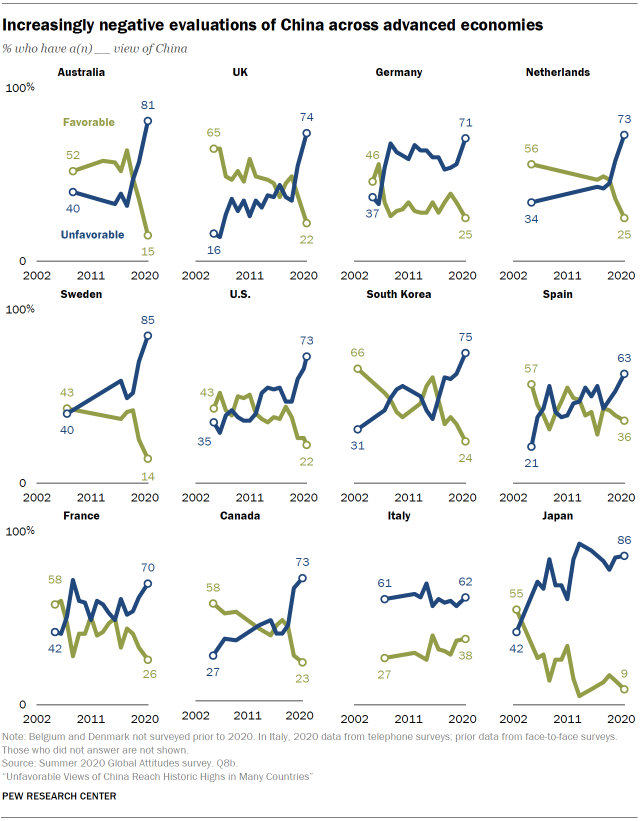

A new Pew Research Center survey of public opinion in 14 advanced industrial economies about China show that 85 percent of Swedes – Swedes – surveyed view the country unfavorably, compared to 40 percent in 2006. According to Pew, “[v]iews of China have grown more negative in recent years across many advanced economies, and unfavorable opinion has soared over the past year.”

And soared it has indeed. For example, 81 percent of Australians surveyed expressed negative views about China in this year’s survey, compared to 57 percent last year. Crucially, in the United States, negative opinion of China has increased by almost 20 percent since 2016, when President Donald Trump assumed office, to 73 percent this year; 13 percent of that increase was from last year alone.

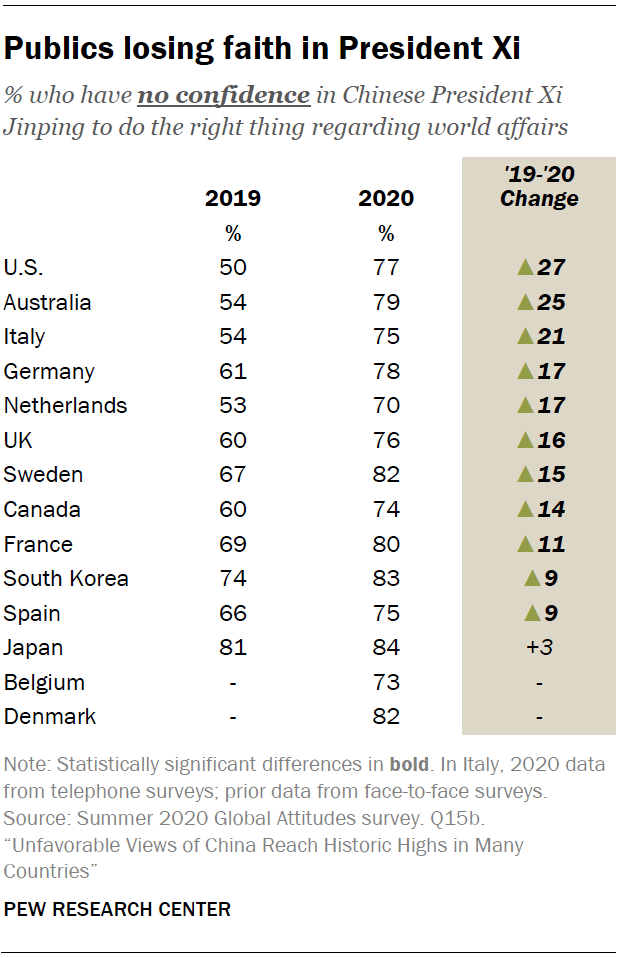

Xi himself isn’t exactly Mr. Popular at the moment in these countries. Eighty-three percent South Koreans surveyed say they have “no confidence in Xi Jinping to do the right thing when it came to world affairs,” an increase of 9 percent from last year. Americans seem to be particularly angered by Xi’s recent (in)actions: lack of faith in the Chinese president has increased by a staggering 27 percent over the past year, to 77 percent today.

While it is certain that the ongoing COVID-19 crisis may have led to some of the dramatic figures reported by Pew, eyeballing the results makes two things clear. First, negative opinion of China has been on the rise since 2006, for many countries steeply so since Xi became China’s president in 2013. Second, China’s deep economic ties with many of the countries that were surveyed has not made much difference in arresting public pessimism about the country globally. Germany, China’s largest trading partner in Europe in 2016, serves as a case in point: 71 percent of Germans have an unfavorable opinion of China, with 78 percent of Germans having no confidence in Xi’s ability to handle world affairs favorably.

The Pew results come at a time of global pushback against China’s actions and a concomitant commitment to strengthening security and economic architectures in the Indo-Pacific. Germany, for example, made news last month when Berlin released an Indo-Pacific Strategy. While critics lamented its lack of muscle – one noted that compared to the United States’ regional policy, “German strategic thinking appears meek” – the very fact that Berlin, not traditionally disposed to taking a hardline when it came to China, would release such a document was significant.

And of course, publics of the three Quad countries polled by Pew reacted very harshly toward China. Eighty percent of Americans, Australians, and Japanese surveyed, put together, hold a negative view of China this year. (While 46 percent of Indians surveyed last year held an unfavorable opinion of China, one can safely assume that were such a poll to be taken today, that number would be significantly higher.)

This suggests that should governments of these countries increasingly adopt hardline China postures the public could be swayed by them. This, in turn, presents an opening for them to recalibrate their China policies and attune them to match the country’s actions.