China’s fifth plenum communique has all the hallmarks of retro Soviet oratory combined with all the future path-dependencies of the Amstrad computer. While innovation in science and technology goals remain important, critical policy areas are being downgraded or ignored as the planning stages of the 14th Five-Year Plan near completion. This communique and the proto-14th Five-Year Plan that it presages highlight a continuation of regressive economic policy, not a bold leap into an innovation-led future.

Much analysis has focused on the prominent position of innovation in science and technology policy in the communique. But innovation was already the highest policy priority area in 2016’s 13th Five-Year Plan. More important than the continuation of innovation as the highest policy priority are the higher position of manufacturing, the lower position of rural reform and a shift in rhetoric from “opening up” to “international cooperation.”

Plenums are annual meetings of the full Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). There are seven plenums in a five-year administrative term, the most important being the Third, Fourth and Fifth Plenums. The Third Plenum is the administration’s first attempt to really set its policy agenda, so its communique normally has the most practical policy measures. The Fourth Plenum is mostly concerned with party-building, ideology and governance matters – providing the internal party renewal that elections would in a democratic system. The Fifth Plenum is mostly an analysis of the previous five-year plan and sets the policy blueprint for the coming plan.

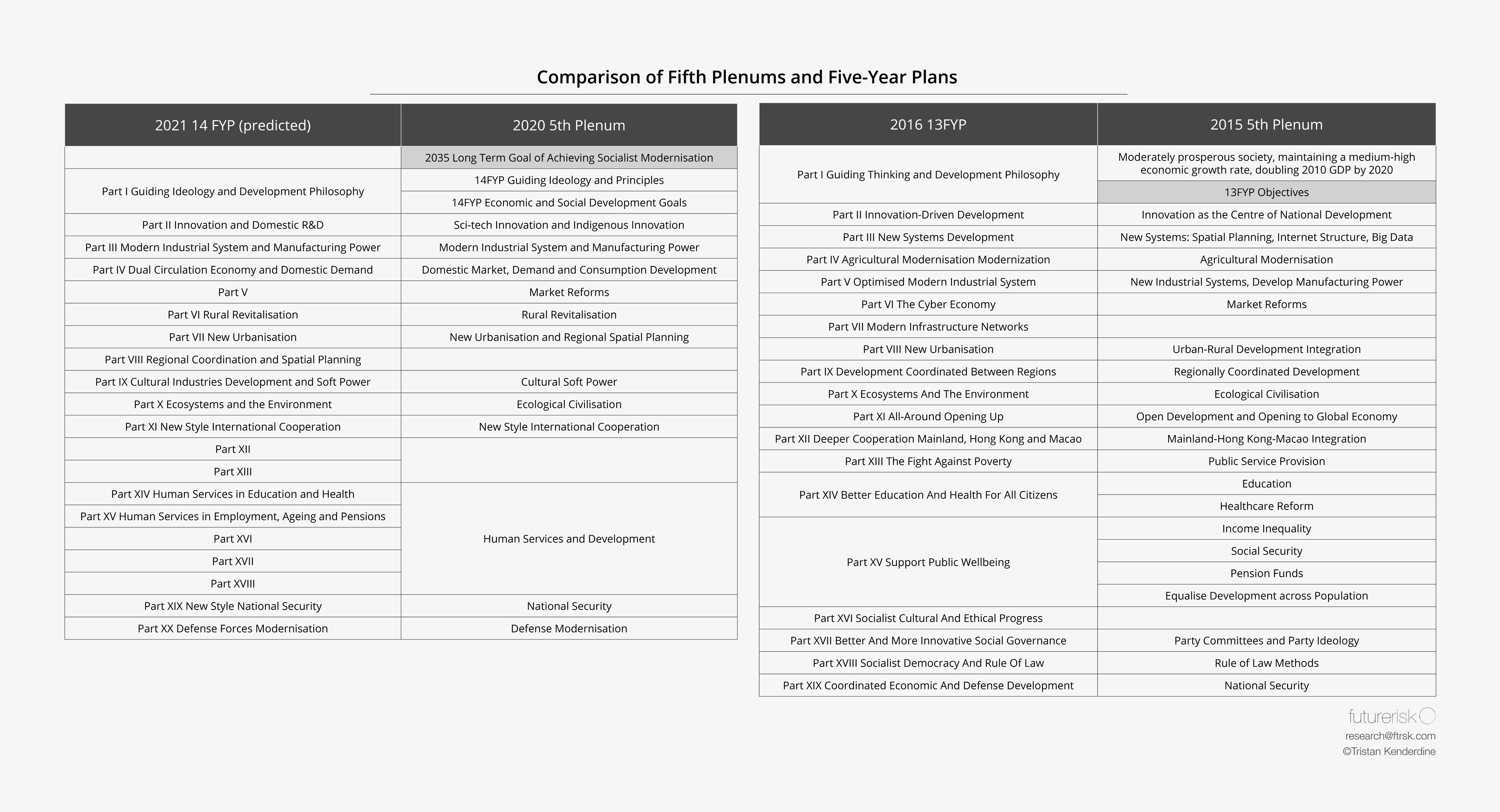

Comparing the 2015 and 2020 Fifth Plenum communiques and the resulting Five-Year plans, we can see a reshuffling of several policy priorities. And we can also construct a reasonably accurate shadow of the structure of the 14th Five-Year plan, which will be tabled in March 2021.

The clearest takeaway is that this 2020 communique is already much closer to the structure of a completed five-year plan. While the 2015 communique contained all the elements that would go into the final plan, they were more policy protozoic; the 2020 version is already nearly ready to be numbered and structured into the formal policy document.

More interesting than the continued apex of innovation as the central driver of economic development is that manufacturing policy has risen to the secondary priority. This does not mean that manufacturing was not important before, but it does mean that new policies for advanced manufacturing are forthcoming and I would expect a codification of the manufacturing power policy to be highly structured and well thought-out in the 14th Five-Year Plan.

The dual circulation policy is likely to fill in the Part IV slot. This is probably the most important policy area, but also one that is theoretically, ideologically and practically the thinnest. Expect a lot of proto-policy maxims here, without clear goals or metrics. This area will be a real chance for the Liu He side of economic governance to stake a claim for successful transition to domestic demand. However the policy development priority of strong domestic market demand is naïve without competition policy and reform. Part V will focus on deepening financial reform, but we do not have a title or clear idea of what the market reform portfolio will look like in the final plan.

Parts VI, VII and VIII – on rural revitalization, new style urbanization and regional spatial planning, respectively – are where we will see most practical policy measures, but this is also where the Party consistently hopes for a policy panacea. Rural revitalization dropping from the fourth to sixth priority is telling. Rural reform is arguably the biggest institutional blockage to China’s economic development, the second being its aging population and problems with public service provision. But health care, aging demographics and pensions consistently rank lower down the Party’s policy priorities than rural reform, which usually sits alongside technoindustrial development and marketization reforms.

Viewed from the “Soviet collapse” narrative, the rural, urban and regional policy portfolios represent some of the biggest policy dead-ends. However from the successful China development model narrative, they are the most forward deployed command-economy policy mechanisms, and the Party is too far committed to back out now. Expect grand plans and mega projects in this section in the 14th Five-Year Plan. At the 19th Congress, however, no clear successor to the role that Zhang Gaoli played in the 18th has emerged, so it is hard to imagine any great successes in spatial planning in the 20th Party Congress absent clear policy leadership. Spatial development, though, is the single greatest selling point of planned economies and it will be interesting to see the further development of the spatial planning model – not only the main regional poles of the Greater Bay Area, Jing-Jin-Ji, the Yangtze River Delta and Yangtze River Economic Belt, but also the variety of lower-level provincial and interprefectural spatial planning models.

Against the backdrop of these progressive spatial plans though, there are some serious deficiencies. In the 13th Five-Year Plan there was a progressive section on new networks, including domestic market structure, logistics systems, the Internet Plus plan and big data systems development. However, taking the logistics network model as an example, inter-modal hub development for rail-road-sea integration has been poorly implemented. These systems are needed for the continuation and development of the coastal export model, the China Rail Express system to Europe via Eurasia, and the development of the domestic logistics system on which the dual circulation demand model is due to be based. But in domestic logistics development over the past five years, the inter-provincial competition system has caused inefficient practices to creep in, with too many low quality infrastructure builds and not enough high-quality or systems development.

Ecological civilization is a well-established a codified policy priority by now. However, the 18th Party Congress Fifth Plenum Communique had a huge array of detail on ecology and ecosystems and the policy form that ecological civilization could take in order to achieve its goals. Perhaps the lower level of detail in this communique implies advanced policy implementation and less need for aspirational goals. But it is more likely that ecological civilization, like rural revitalization, has suffered a policy deadening under Xi Jinping Thought and that good policy minds and creative ideas have been chased away or otherwise silenced. The result is drab boilerplate Party-speak rather than any novel problem-solving ideas for the coming five-year term.

The Fifth Plenum communique’s rhetoric of a shift to a high-quality development is also a little hollow. This has been on the policy books for over five years. With the 14th Five-Year Plan draft around the corner, we really need to be seeing what this high-quality growth is going to look like, and what institutions and mechanisms are going to ensure quality, standards and the transitions to world-class systems that the Party is promising China’s people.

The 14th Five-Year Plan section on “new style international cooperation” will be important. This section will be where the CCP lays out its plan for a multipolar geoeconomic world. For the Fifth Plenum communique, it is interesting to see “high-level opening” and “win-win” both occur higher in the order of the paragraph of international cooperation than the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which has dropped down to the last priority on the list. The policy goals will be to integrate China’s parallel institutions into maintaining domestic growth, developing new markets and continuing the deployment of the offshore industrial base model.

Expect the geoindustrial policy of international capacity cooperation to be canned and a new form of “going global” to reappear; for the hollow diplomatic rhetoric of win-win to not be backed up by any practical policy; and for doubt to be introduced into the BRI (or it being morphed into some new geoeconomic policy container). China is likely to begin a coordinated withdrawal of geoeconomically deployed capital along the BRI, but cannot pull back ideologically from the policy.

The stark drop-off in policy innovation and problem-solving as we near the end of Xi Jinping’s second term is indicative of a culture of fear in progressive policy-making. Rather than innovating into a high-technology manufacturing future, China’s regressive, Soviet-esque economic policy is likely to stunt innovation and technology development. The indications from this Fifth Plenum communique are that a dearth of policy ideas has set in, not a plethora.

Tristan Kenderdine is Research Director at Future Risk.