India and the Philippines held the 4th meeting of the Joint Commission on Bilateral Cooperation virtually on November 6. The meeting was co-chaired by Indian External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar and Secretary of the Philippines Department of Foreign Affairs Theodore Locsin. According to an Indian readout of the meeting, “they agreed to further strengthen defence engagement and maritime cooperation between the two countries, especially in military training and education, capacity building, regular good-will visits, and procurement of defence equipment.”

The readout also mentions cooperation around combating the COVID-19 pandemic, counterterrorism, trade and investment, agriculture, capacity development, educational exchanges, visas and other issues.

“On regional and international issues, both sides agreed to coordinate closely at multilateral fora. EAM and Secretary Locsin reaffirmed their commitment to a multifaceted partnership in line with India’s Indo-Pacific Oceans Initiative (IPOI) and the ASEAN’s Outlook on Indo-Pacific to achieve shared security, prosperity and growth for all in the region,” the readout also notes.

While the Indian readout suggests that both sides apparently covered the entire gamut of issues facing both countries — which, cynics would suggest, imply that the meeting lacked substance — it was marked by a significant absence: cooperation to combat natural disasters and associated humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HA/DR) efforts found no explicit mention.

To be sure, the 10-nation Association for Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and India formally remains committed to jointly fighting climate change. India’s Indo-Pacific Oceans Initiative flagged off by Prime Minister Narendra Modi at the East Asia Summit last November also includes disaster prevention and management as an area of focus. But India and the Philippines would both be better off with greater bilateral cooperation in these areas as well.

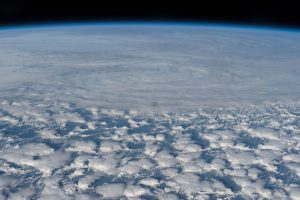

As an example, India’s record at evacuating large number of people ahead of devastating cyclones – as became clear with Cyclone Fani last May as it was about to make landfall in the eastern coastal state of Odisha – has earned the country much-deserved praise. The evacuation plan which involved “2.6 million text messages, 43,000 volunteers, nearly 1,000 emergency workers, television commercials, coastal sirens, buses, police officers, and public address systems blaring the same message on a loop …” as the New York Times described it, proved to be very effective as lives lost from the super cyclone was minimal.

But this was simply not a matter of communicating a message across to the affected public effectively. It also involved “the almost pinpoint accuracy” of Indian meteorological early warnings which had led authorities to craft an appropriate evacuation plan, as United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction described the response while praising it.

The Philippines’ challenge with extreme weather events became glaringly clear once again in the beginning of this month when Super Typhon Goni hit Catanduanes island and Albay province, causing massive infrastructure damage as the Philippines government found itself scrambling for a response.

To be sure, geography necessarily dictates differences in response to extreme weather events, between what needs to be done for islands versus a peninsula. That said, India’s experience in early warning, resilient infrastructure construction, as well as evacuation planning are all things the Philippines could profitably learn from.

Both India and the Philippines also stand to benefit from much greater dialogue around long-term effects of climate change and ways to address climate-change induced migration which feeds into gender issues, violence and conflict. India is contemplating a “managed retreat” plan for residents of the Sundarbans, the world’s largest mangrove delta – a plan, scholars have argued, that does not address underlying socio-economic and cultural costs. There is much common ground between the two countries to push dialogue on these issues on to their bilateral agenda.

Such “softer” issues may not be exciting enough for many, compared to the possibility of hard political-military cooperation. But, given fundamental strategic differences in the Philippines’ and India’s thinking about China, there is a firm ceiling to what the two can do together in that space. On the other hand, cooperation around disaster planning and climate change is a low-hanging fruit which, patiently pursued, may lead to deeper relations in the future, bringing with itself strategic gains for both countries.