When senior Biden administration officials sat down for their first in-person meeting with Chinese counterparts in Alaska in March, they were in for a surprise. Yang Jiechi, China’s top diplomat, broke with diplomatic protocol to lecture Secretary of State Antony Blinken and National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan for 15 minutes without translation. The two sides continued to talk behind closed doors, but the public dressing down will not make it any easier to cool tensions, including de-escalating the tariff war and technology restrictions.

Alaska was the latest manifestation of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s elevation of China’s political and geopolitical considerations over traditional economic concerns, particularly maintaining high rates of growth. This theme runs throughout China’s recently released 14th Five-Year Plan, in which national security issues permeate discussion of traditional economic spheres. That transition has been underway for some time, but it is now becoming far more formal and explicit. Xi has announced that this year – the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party – marks a “new development stage” in which the focus shifts from “getting rich” to “becoming strong.”

This is a transition that the rest of world – policymakers, firms, and investors – will need to adjust to. Traditional ways of understanding Beijing’s hierarchy of priorities – particularly the balance between economic growth and other objectives – are shifting. Important changes in the way Beijing defines China’s economic growth targets illustrate the challenges, and the need to develop new tools. This shift requires developing better ways to read the policy tea leaves in Beijing, lest China watchers be caught flat-footed by unexpected economic or geopolitical decisions.

This year’s five-year plan is the first to not set an average annual growth target in advance, as Xi pushes officials to focus less on the speed of growth and more on its quality: environmental protection, reducing financial risks, and achieving technology aspirations – in particular, boosting self-reliance in the critical technologies at the center of China-U.S. tech competition, including semiconductors, software, and advanced manufacturing.

For 2021, Beijing did set an annual growth target, but made it a very unambitious level of “above 6 percent.” Due to base effects from 2020, when the pandemic slowed China’s growth down to 2.3 percent, hitting that benchmark requires almost no economic expansion from China over the course of the year. The message to local officials is clear: the flexibility should motivate them “to devote full energy to promoting reform, innovation, and high-quality development.”

The dilemma for those following China’s growth policies is that while Beijing may be moving away from rigid targets, it is not shedding its pervasive intervention in the economy. China’s leadership are balancing two main tasks for the economy at any given time: keeping growth high enough to prevent rising unemployment and discontent, but not over-stimulating the economy and worsening debt risks or speculative bubbles in real estate or equities. Beijing uses the media to convey to the rest of the system – including China’s vast bureaucracy – how it should walk that balance at any given time.

There are still no criteria for charting Beijing’s “reaction function” on these policies as one might follow the Federal Reserve. China’s official unemployment data, for example, provides a biased picture of labor markets – a highly sensitive topic for the leadership, given risks of social instability – and doesn’t yet serve as benchmark for policy. Growing prominence of mentions of labor conditions is a better signal that the leadership is prioritizing these issues and wants local officials and regulators to as well.

How do we navigate a world in which growth targets and other traditional anchors of Chinese policy are losing importance, but politics is still in command? One solution is to look more closely, and rigorously, at the megaphone that Beijing uses to communicate its policy views – the Chinese media.

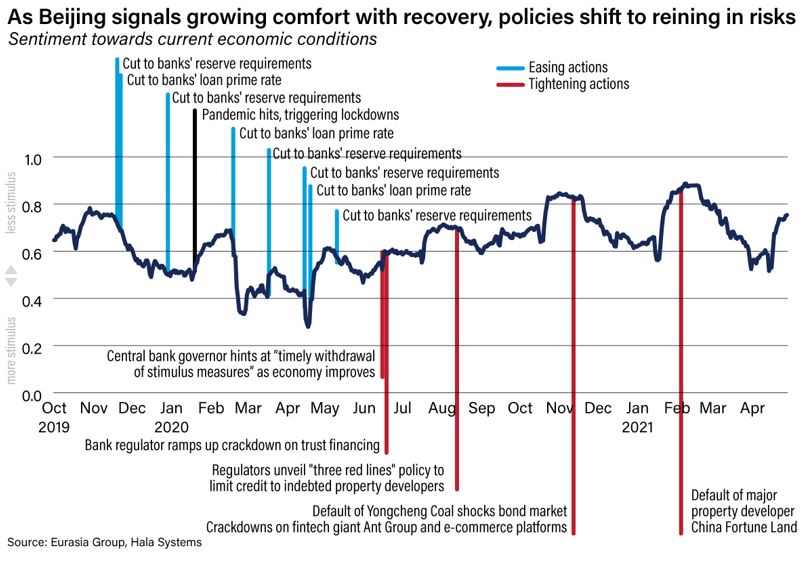

Research by Eurasia Group, Hala Systems, and a Columbia University political scientist has found that there is a strong association between policy decisions and previously expressed sentiment about the economy by the political leadership in China’s media. This is the basis for an index created to assess the signals the leadership is sending to the rest of the system as well as how these signals are being interpreted and rebroadcast. A high level for the index indicates that Beijing is signaling comfort with current growth levels and a willingness to back off stimulus or even tighten policy.

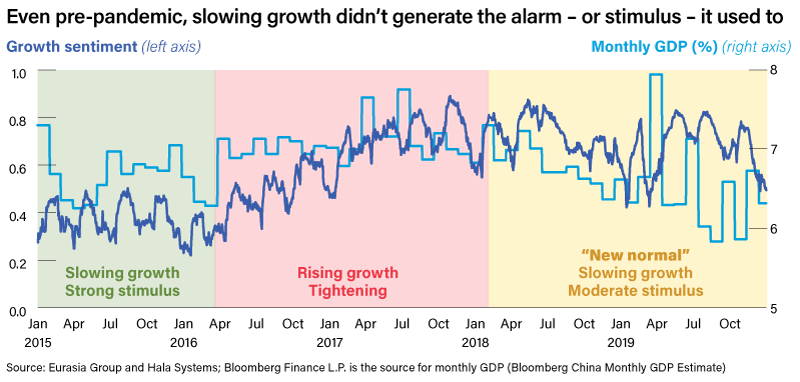

A long-term view of the index illustrates how Xi’s tolerance for lower growth, made official in the latest five-year plan, has been underway for several years. Compare the 2015 period, which saw low growth, dissatisfaction by Beijing in China’s economic performance (reflected in the low reading on the sentiment index), and aggressive stimulus measures, with 2018-2019, when growth slipped to a decades-low level only to be met with moderate concern and stimulus from Beijing.

What does the index suggest about Beijing’s intentions now? The index peaked in February, with Beijing full of confidence after posting growth of 6.5 percent in the fourth quarter of last year, better than any large economy. Since then, the index has remained positive but bounced around amid mixed economic data. Officials are broadly comfortable with conditions but reluctant to move too quickly in withdrawing stimulus given uncertainties as to the strength of the rebound.

What does the index suggest about Beijing’s intentions now? The index peaked in February, with Beijing full of confidence after posting growth of 6.5 percent in the fourth quarter of last year, better than any large economy. Since then, the index has remained positive but bounced around amid mixed economic data. Officials are broadly comfortable with conditions but reluctant to move too quickly in withdrawing stimulus given uncertainties as to the strength of the rebound.

That translates to fine-tuning in macro policy, particularly monetary policy, but a willingness to continue with a flurry of recent measures to rein in financial and economic risks. These actions include tightened restrictions in the property sector, renewed scrutiny on shadow banking products such as trusts, and the continued clampdown on key fintech companies, which ensnared Jack Ma’s Ant Group and led to the cancellation of the firm’s blockbuster IPO.

If economic activity or confidence falls too far for comfort, Beijing will slip back into support mode — a shift that would be reflected in signals by the Chinese leadership to the rest of the political system through the media, and a corresponding a drop in the sentiment index.

Sentiment analysis likely has also a lot to offer as a tool for understanding Beijing’s evolving geopolitical considerations. For example, a study by University of San Diego political scientist Kacie Miura examined China’s foreign policy dispute with South Korea in 2017, and found that provincial officials in China were more likely to signal harsh rhetoric against South Korean firms in their local media – and to retaliate against them on the ground – if their cities were not economically dependent on those firms. That kind of early warning signal will become increasingly important for firms exporting to or operating in China as Beijing embraces economic coercion as a foreign policy tool – as the current trade war with Australia highlights.

The bottom line is that in the highly politicized, top-down governance environment that Xi has created, policies are becoming more dynamic and less anchored to traditional norms. That makes it imperative to correctly interpret the signals coming from Beijing to the rest of the system and to respond in real time. Among the highest priorities will be getting a handle on when China’s leaders are comfortable enough with growth to elevate other priorities, from tackling pollution to going toe-to-toe with Washington.