Something unusual is happening in Colombia.

The country that was not long ago described by then-candidate Joe Biden as the keystone of U.S. policy in Latin America and the Caribbean, one that most IR textbooks will tell you has for decades been guided in its foreign policy by a doctrine of respice polum or looking to the north, has seen of late what appears to be a silent but emphatic turn eastward, toward China.

Chinese characters, once unseen in the South American country, now appear splashed on banners hanging over Chinese-built highways. Colombian students and researchers are exchanging limited Fulbright scholarships for hundreds of Chinese studying opportunities in every conceivable field. National TV stations are increasingly airing Chinese-made content, from historical dramas to documentaries on the Chinese experience of development. And even high-ranking Colombian officials have praised China before international bodies for its progress in human rights. To the skeptical observer, something appears to be afoot.

So what is behind the thinking of Colombian President Iván Duque’s administration? Is this meant to be a definitive shift away from the U.S. and into the arms of China?

China and Colombia Elbow-bump in the Pandemic

Evidence of increased China-Colombia convergence can be found in almost all spheres, but no area best exemplifies this than sanitary cooperation during the pandemic

Colombia is among the hardest-hit countries by COVID-19. It has remained in the top 20 of countries by total cases since July of last year, and it is today ranked 11th in total deaths, with close to 80,000 deceased, according to the Johns Hopkins COVID-19 dashboard. Prolonged and strict lockdowns have been implemented to slow down the two past waves of new cases, but they have come at a price: GDP contracted by 6.8 percent in 2020, poverty increased by almost 7 percentage points, reaching 42.5 percent, and the latest unemployment data points to a February 2021 rate of 15.9 percent, the highest for that month since 2004.

A third wave, now underway, is being faced with new lockdowns in the most affected cities. This time, however, people are going to the streets to protest, condemning the economic costs of the measures. The marches have devolved into outbursts of street violence and attacks on public property.

Desperate for a way out, the Duque government has eagerly accepted Chinese aid during the past year. In May 2020, as number of cases steadily crept up, and with little concrete aid forthcoming from the U.S. at the time, Colombia received $1.5 million worth of ventilators, test kits, facemasks, and other equipment from the Chinese government.

By June, the distribution of aid had moved to the local level, with the Chengdu and Xi’an city governments donating supplies to their Colombian sister cities, Ibague and Neiva. Local Chinese communities also mobilized donation drives of their own, distributing much-needed food and protective equipment in cities throughout the Colombian interior, in the Caribbean coast, and along the Pacific.

Later, in response to the devastation caused by hurricane Iota to the Caribbean archipelago of San Andres, Providencia, and Santa Catalina, the Chinese government made two donations for reconstruction of US$500,000 each, one in November and a second one this past March.

With each action, the perception held by the Colombian public and decisionmakers of China has undergone deep transformations: What was once a mere customer has, in the words of Foreign Minister Claudia Blum, become a strategic partner and even a friend.

Duque Goes to China… Again?

This steady march to friendship reached a new climax on March 20, 2021, during an exchange of video messages between Duque and Chinese President Xi Jinping. The videos, aired in the middle of the annual assembly of the U.S.-led Inter-American Development Bank, marked the arrival to Colombia of the fourth shipment of Chinese-made vaccines against the coronavirus. By that date, as the country entered its third wave of cases, 76.6 percent of all vaccines received by Colombia had come from the Chinese pharmaceutical company Sinovac Biotech. In other words, it was China that was once again coming to the aid of the Colombian people in their hour of need.

Xi’s video address, directed to the Colombian people, stressed the power of friendly cooperation in the face of common challenges to bring the two countries together, regardless of distance. Duque, for his part, profusely thanked his counterpart for the speed and pragmatism with which China made its vaccines available, vowing to work toward a stronger bilateral relationship.

To crown the exchange of pleasantries, Duque concluded his speech with an announcement: “I hope, President Xi, to visit your country once again toward the end of this year, and to continue making of the Colombia-China relation one that transcends future political changes in our countries and that enhances our commercial, political, and diplomatic relations for the coming decades.”

A second visit by Duque would be unprecedented. It would mark only the sixth state visit by a Colombian president in the 41 years since the establishment of diplomatic relations; it would also be the first time that a Colombian president visits China twice during their term.

The BRI Question

More important than the milestones that the trip itself represents are the likely commitments made that could set the course for the coming decades. Other than deepening the agreements already made by Duque during his first state visit in July 2019, some (including the author of this piece) see the possibility that this one could conclude with Colombia’s adherence to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), if only unofficially.

For a government that has for long stood firmly by the side of the United States, joining China’s flagship global connectivity project would certainly mark a deep departure, especially if it was Duque, an accolade of former President Alvaro Uribe, who took this step. The timing of this is also unusual, given the increased confrontation between the Biden administration and China.

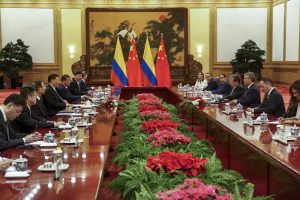

There are, however, signs that point to this possibility. For one, during Duque’s 2019 visit, the Colombian government launched a Colombia-China Initiative, a mechanism meant to promote the BRI’s objectives of connectivity without formally joining the initiative.

Then, in early March 2020, Chinese Ambassador to Colombia Lan Hu, as well as the Colombian deputy foreign minister, explicitly mentioned plans to move in the direction of joining BRI. The deals, which were to be signed during a 2020 visit by Duque to China, appear to have only been disrupted by the pandemic. More recently, in a February phone conversation between Xi and Duque, the two sides discussed creating greater synergies between the two initiatives.

Adios, United States?

While the agenda for a likely 2021 state visit remains uncertain, the fact that the two countries have quickly grown fonder of each other is evident. Will Colombia give the U.S. the cold shoulder?

That’s unlikely, at least not intentionally. As Duque set out in a November speech, it is his administration’s intention to deepen economic ties with China while maintaining Colombia’s longstanding, value-based partnership with the United States.

And this makes sense: China is better positioned today, both in terms of capacities and interest, to participate in the reactivation of the post-COVID Colombian economy than a U.S. that is just being put in order by the new Biden administration. With elections in Colombia coming up next year — and with the leftist Gustavo Petro taking a considerable lead ahead of other candidates — the Duque administration is ready to take a win where it can find it, regardless of origin.

A tight embrace between Colombia and China may very well be the outcome. For one, because, despite the reaffirmation by White House officials of the strategic nature of the U.S.-Colombia alliance, it is Washington that has left a vacuum of leadership in the region — one being filled by extra-regional powers. Differences between the two leaders on issues like the implementation of the peace agreement may also put some distance them.

In the medium-term, it may not even be a decision over which the national government has a say, with China-Colombia ties increasingly being developed by actors outside of the presidential palace like local governments, companies, universities, and private citizens.

Friends by happenstance, not by choice, but friends nevertheless.